An interest in what used to be called primitive art is often dabbling in things it can’t admit to, like aggression and violence, living vicariously in a wilder and fiercer world than the safe one most of us inhabit, at least for now.

My latest encounter with real wildness came entirely through a couple of books, which catalogue 598 choice objects from a private collection of Oceanic art, two volumes so unwieldy that, like old people increasingly housebound, they haven’t moved for months from the room in which I finally parked them, which nowadays I don’t have much occasion to visit except to scan these records of John Friede’s amazing collection. The day I brought them here is stamped inside their front covers, November 28th of last year, the day of my second visit to the big exhibition of Pacific island art at the Royal Academy.

They are a spin-off of this exhibition, or a substitute for it which would last long after it ended, both bigger and smaller than it was, more compact and more unmanageable, since no one had given this material a shape or picked out its themes, which remained for me to discover, if they were there at all.

The fact that certain things are owned by a certain person is interesting to him or her but not to anyone else, unless the collector happens to be John Ruskin or some other figure you are already interested in for a good solid reason outside his collection. Collecting seems the very opposite of public spirited, and yet collections themselves are almost always interesting, if you can get them away from their owners, which you often can if he/she wants the collection to survive him/her, because it has come to represent him and is a kind of self-portrait.

John Friede was obsessed with the art of New Guinea, but had never been there. He knew all the European collections and their keepers, but he wasn’t tempted by the South Seas themselves, or at least put off his visit (which he didn’t soon repeat) until late in his career.

At first I wasn’t interested in the collector, only in his magical collection, or rather the beguiling presentation of it in well-lit photographs that lent all the pieces fantastic immediacy. Many of the objects are small, yet there are fragments of facades, roof posts and large slit-gongs mixed in. But in these books everything is the same size and they all fill the large pages in much the same way.

The Friede collection makes a strong impression because it’s ruled by strong imaginations, John Friede’s and those of the cultures he gravitated to when he knew them only by their artefacts. Early in collecting he decided to focus on one Pacific island, the largest, New Guinea, a small part of the whole Oceanic territory, but still vast. The island is the size of Spain and Italy combined and home to 1000 different languages.

Despite such unencompassable variety, certain over-arching themes appear in these objects. Dancers follow a powerful cultural prompting to take on the character of birds, and mask after mask portrays a human face taken over by a beak, as if pursuing an urge to become all beak, and thus all bird, as if set on leaving human form and consciousness behind altogether.

In a whole class of figures the beak turns into something else, a flute which the bird-man’s hands then play, or an elephant’s trunk which merges imperceptibly with a snake-like extension from the abdomen rising to meet it. Such grotesque distortions are seen by Friede as crucial goads in jolting the sleeping Western imagination awake.

Human beings are constantly found subsumed in other forms, camouflaged as elements of communal food dishes which themselves resemble canoes, where each separate human face assumes dish-like form.

There’s a powerful formal preference for concentric arrangements with the face at the centre. Sometimes it feels like the disappearance of all individuality, subsumed in irresistible general forms. Sometimes the human form is peeled like an onion to see if there’s a permanent core inside.

It can feel like regression to earlier reptilian stages (above), or it can seem a painful evisceration as the outer layers are cut away looking for more or different life inside (below), like a medical experiment testing the limits of the organism.

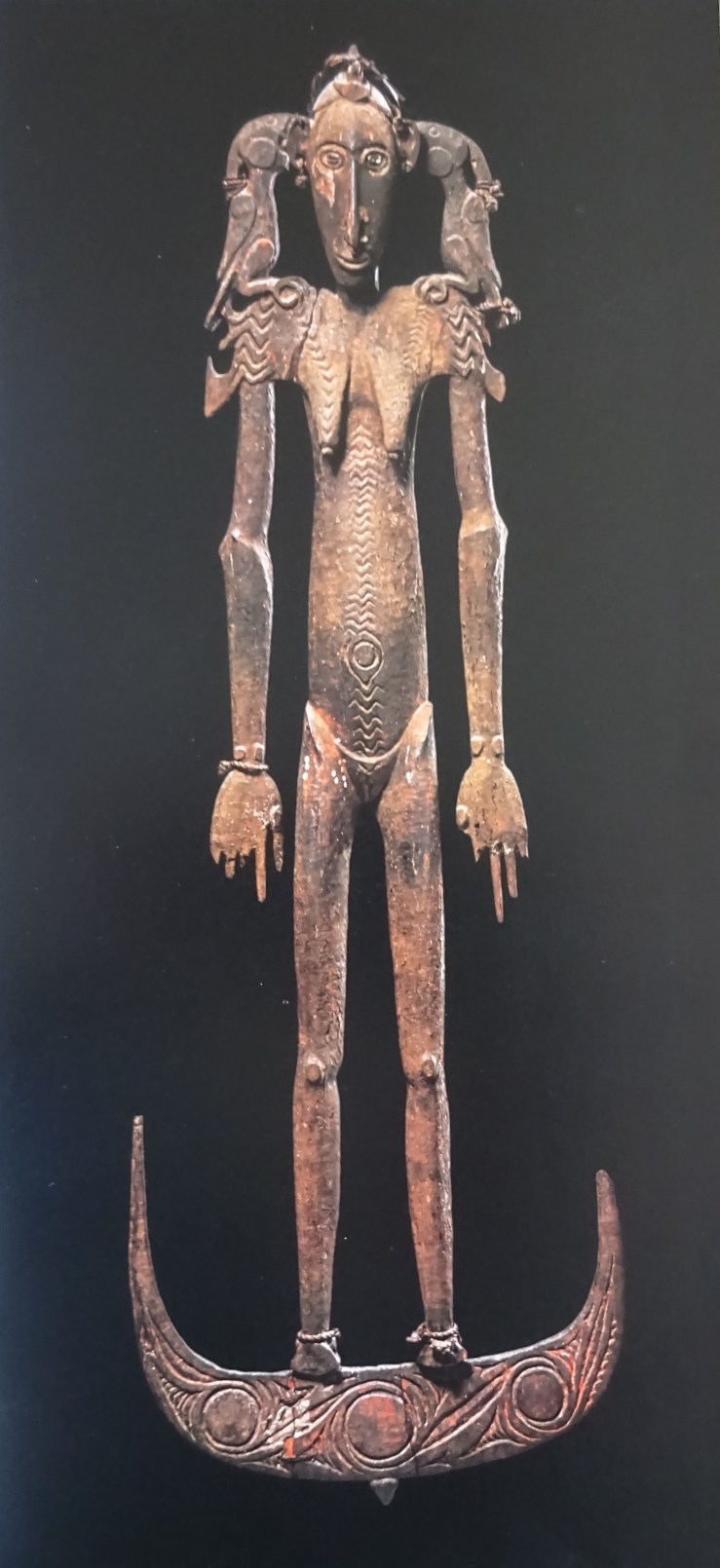

This piece is one of the suspension hooks so common in the artefacts of the East Sepik cultures. Perhaps it has its origins as a practical device, a way of hanging food out of the reach of marauding animals, but it plays a powerful spiritual role as well, in the group’s relations with higher powers, for whom offerings are left hanging from such hooks. Much of the local figure sculpture is associated with the hooks, so ubiquitous that they present themselves almost as body parts, fulfilling a function so essential they look as if they’ve been internalised or only need a suitable occasion to erupt from the body, as seems to happen with the prong-man and woman that produce hook-like projections, not actually usable for hanging things, on other parts of the body. In this culture we can understand the usefulness of a hook-deity who bristles with them, like a crocodile’s sharp bumps on the spine, more active and energetic than smooth flesh.

prong-woman standing on her hooks

prong-woman from behind

Ceaseless ingenuity is applied to turning one thing into another—a three-dimensional pig can mirror a two-dimensional crocodile, and a man and a bear can face off against one another, sharing the same set of legs. A smaller creature stuck to or exuded by the body of a larger one is one of the clearest signs that such a transformation is taking place. The pig below isn’t easily recognisable but is clearly some kind of creature.

pig mirroring crocodile

The growth emerging from prong-man’s chest is a bony structure at the top and nurses a bird-embryo lower down, an altogether weirder mutation. There’s a whole system of mythic creatures buried here, how comparable to the familiar Greek set we will never be able to say because it never appeared in print while it was alive. Perhaps this obscure system is all the more alluring because permanently lost and indecipherable, because the chance to write it down came too late, after corruption by strong foreign ideas.

Helmet-bird-shield-man can be all these things simultaneously, all the more successfully because so much detail has been washed away by the weather.

One of the most enigmatic recurring forms in the collection is masks or covering for the whole head made of basketry, which is nearer to a living, breathing material than wood or clay, yet seems more far-fetched, less life-like when woven into these body-forms. The results are not solid bodies, and probably have much shorter life expectancy than the more common wooden masks, and though they obviously required hours to make, are perishable like grass. In this fragility lies some of their appeal—how do you make them take on or keep their shape? Inevitably there’s something impromptu or lopsided about all basket-beings. They seem more like domestic appliances than art, and unsuitable for ceremony or ritual.

Some of the most appealing objects in the collection are shown blurring their identities under the conditions in which they are photographed, like the ‘mask’ (not obviously wearable) whose features, smeared sideways by shadows, make it look as if his two mouths are crossing each other and will merge. It’s a strangely effective graph for slurred speech, and the bemused expression or baffled grin on this face is partly down to the senile decay of its substance over time.

Something similar operates with the so called ‘fragmentary mask’ below, like an animal’s skull abandoned in a field, that’s now brought indoors where every tremor of its surface becomes full of meaning.

Something similar operates with the so called ‘fragmentary mask’ below, like an animal’s skull abandoned in a field, that’s now brought indoors where every tremor of its surface becomes full of meaning.

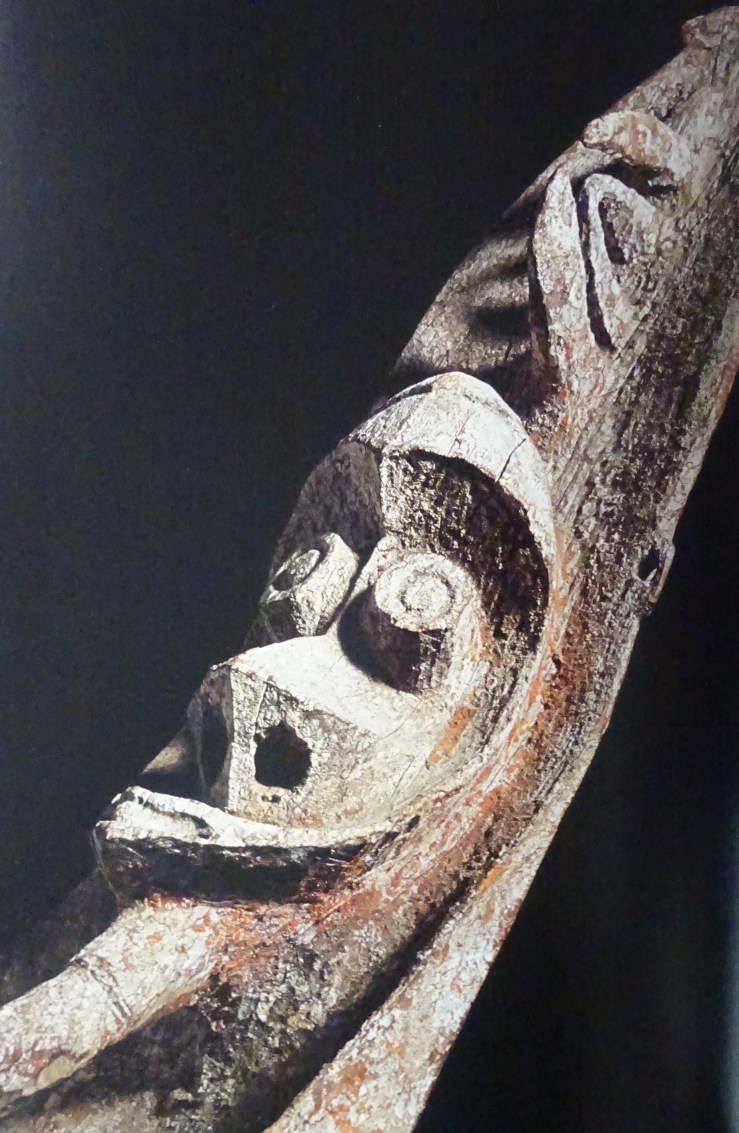

Among the most evocative and mysterious images are the close-ups of bone daggers usually made from the femurs of cassowaries (large flightless birds) and intended purely for display during initiation ceremonies, not serious equipment for killing your enemies. Maybe the upper ends of these bones, ruined by carving which turns them into works of human art, have partly sought and partly stumbled into the appearance of decay, that now makes them such suitable mementoes of death in forgotten battles. First below is a weeping face losing clear definition, while the next one is another bird-man that is particularly hard to believe in as a serious weapon.

The two big books were published in 2005 when John Friede gave a significant part of his collection to a museum in San Francisco, who I imagine helped make them such lavish productions. An even more ambitious series of publications is announced in his essay in the initial volume.

Trying to find out more about this charming man who has named his collection Jolika after the first syllables of his children’s names, I stumble onto reports of long-standing lawsuits brought by his brothers disputing the inheritance that has funded all the purchases. John Friede isn’t the hard-headed businessman I projected, after all. The money was his mother’s, herself a collector and John her favourite, so some members of the family contend. The magnificent books are defensive weapons in this struggle and argue that the collection is a great cultural good to be preserved at all cost. They have convinced me.

Some are cartoon-illustrations of the history of architecture, like the one called ‘lintel shadow’ which projects a monumental gateway like those three-part compositions at Stonehenge but taller and spindlier, in one sense more imposing, in another more precarious. It led to a ‘stone’ enclosure like an introduction to an underground tomb. It led ‘underground’ or nowhere, and fit the idea of a shadow of architecture by being out of true in every axis and every dimension. It was stony in its form–big lumps, scored with accidental grooves and gouges, which lent a kind of ‘authenticity’ to the ruined masses, yet also made you suspicious. As you got nearer, a sliver of the air beyond appeared between adjacent ‘blocks’, which were coloured a convincing mottled gray but gave out a hollow sound if you tapped them.

Some are cartoon-illustrations of the history of architecture, like the one called ‘lintel shadow’ which projects a monumental gateway like those three-part compositions at Stonehenge but taller and spindlier, in one sense more imposing, in another more precarious. It led to a ‘stone’ enclosure like an introduction to an underground tomb. It led ‘underground’ or nowhere, and fit the idea of a shadow of architecture by being out of true in every axis and every dimension. It was stony in its form–big lumps, scored with accidental grooves and gouges, which lent a kind of ‘authenticity’ to the ruined masses, yet also made you suspicious. As you got nearer, a sliver of the air beyond appeared between adjacent ‘blocks’, which were coloured a convincing mottled gray but gave out a hollow sound if you tapped them. They were a figment or a fiction, an insubstantial shadow. Doubtless the lintel too, far out of reach, was a partly convincing fake, hoisted up on rickety poles which had had to be extended by bolting smaller pieces to them with crude splints, our first encounter with the sculptor’s habit of flaunting a few ‘mistakes’–revisions or changes of direction she preferred not to smooth over or clean up. ‘Admitting your mistakes’ has here a wonderful feeling of being at ease with your materials (no quotes) and your project. It evolves, and your audience can watch that happening.

They were a figment or a fiction, an insubstantial shadow. Doubtless the lintel too, far out of reach, was a partly convincing fake, hoisted up on rickety poles which had had to be extended by bolting smaller pieces to them with crude splints, our first encounter with the sculptor’s habit of flaunting a few ‘mistakes’–revisions or changes of direction she preferred not to smooth over or clean up. ‘Admitting your mistakes’ has here a wonderful feeling of being at ease with your materials (no quotes) and your project. It evolves, and your audience can watch that happening. Some of the solidest elements are the shadows, especially the sloping platform ‘cast’ by the massive ruined column called ‘barrel’ in Barlow’s title for it (all her titles follow directly after untitled:– ‘untitled: barrel’). This looks like a waffle-structure in metal, or a model of a curving three-storey block of modernist flats, except that unlike other shadows it is supported by unstable poles driven into swampy ground and poking through the surface of the swamp so crookedly you lose faith in them completely. I had enjoyed the messy punctures in the fibrous board that constitutes the horizontal (but sloping) surface, calling up a forlorn watery landscape.

Some of the solidest elements are the shadows, especially the sloping platform ‘cast’ by the massive ruined column called ‘barrel’ in Barlow’s title for it (all her titles follow directly after untitled:– ‘untitled: barrel’). This looks like a waffle-structure in metal, or a model of a curving three-storey block of modernist flats, except that unlike other shadows it is supported by unstable poles driven into swampy ground and poking through the surface of the swamp so crookedly you lose faith in them completely. I had enjoyed the messy punctures in the fibrous board that constitutes the horizontal (but sloping) surface, calling up a forlorn watery landscape.

The most entertaining conglomerate is saved for the last of the three rooms. It is called ‘blocks on stilts’, which doesn’t begin to do it justice. It consists of four towers (you will have to count them more than once before you believe there are only four, and you will think you have disentangled them only to find they have mixed themselves together again). In some sense it is a simple idea, a set of four-legged frames, each of them existing to raise one impossibly bulky rectangular-solid impossibly high.

The most entertaining conglomerate is saved for the last of the three rooms. It is called ‘blocks on stilts’, which doesn’t begin to do it justice. It consists of four towers (you will have to count them more than once before you believe there are only four, and you will think you have disentangled them only to find they have mixed themselves together again). In some sense it is a simple idea, a set of four-legged frames, each of them existing to raise one impossibly bulky rectangular-solid impossibly high. Some time after finishing this, I remembered my calculation that there are 12 legs in ‘blocks on stilts’, so there must be three towers, not four. But in another sense there are four—when you are there, the parts are magically multiplied and counting them doesn’t settle the question, strictly speaking.

Some time after finishing this, I remembered my calculation that there are 12 legs in ‘blocks on stilts’, so there must be three towers, not four. But in another sense there are four—when you are there, the parts are magically multiplied and counting them doesn’t settle the question, strictly speaking.

Thus, in at least two ways we can’t experience Hilliard’s work fully when standing directly in front of it. This sounds a drawback and so it seems at first, but I’ve come to feel it as a kind of richness—Hilliard dawns on you in stages, slowly. In one of his earliest surviving works, a circular bust-length image of Leicester, the Queen’s favourite, a painting less than two inches across, the background seems an anonymous grey to the naked eye, but is known to have had special attention lavished on it, to be founded on a base of silver which has been selectively burnished to bring it out in patches, probably with an instrument like a weasel’s tooth mounted on a stick, as described in Hilliard’s treatise The Arte of Limning.

Thus, in at least two ways we can’t experience Hilliard’s work fully when standing directly in front of it. This sounds a drawback and so it seems at first, but I’ve come to feel it as a kind of richness—Hilliard dawns on you in stages, slowly. In one of his earliest surviving works, a circular bust-length image of Leicester, the Queen’s favourite, a painting less than two inches across, the background seems an anonymous grey to the naked eye, but is known to have had special attention lavished on it, to be founded on a base of silver which has been selectively burnished to bring it out in patches, probably with an instrument like a weasel’s tooth mounted on a stick, as described in Hilliard’s treatise The Arte of Limning. Hilliard’s self-portrait inscribed with a date of 1577 takes on a new meaning when placed in his French period when it was painted, where he saw artists accorded higher status, and was welcomed into learned circles around writers like Ronsard, newly identified as one of his sitters. Hilliard’s little self-portrait shows him as another gentleman, not a mere artisan, a claim picturesquely fleshed out in the treatise. The liveliness of expression in the features, especially the eyes, the hair and the set of the mouth, is extended by the flying bits of the clothes, as if rocked by a breeze, and the dematerialised edges of the ruff, which will become an even more outlandish feature of many later Hilliard portraits, where regular pattern and an opposing force are locked in endless struggle.

Hilliard’s self-portrait inscribed with a date of 1577 takes on a new meaning when placed in his French period when it was painted, where he saw artists accorded higher status, and was welcomed into learned circles around writers like Ronsard, newly identified as one of his sitters. Hilliard’s little self-portrait shows him as another gentleman, not a mere artisan, a claim picturesquely fleshed out in the treatise. The liveliness of expression in the features, especially the eyes, the hair and the set of the mouth, is extended by the flying bits of the clothes, as if rocked by a breeze, and the dematerialised edges of the ruff, which will become an even more outlandish feature of many later Hilliard portraits, where regular pattern and an opposing force are locked in endless struggle. Perhaps the most astonishing fruit of Hilliard’s time in France is the recently discovered miniature of the young king Henri III which combines hieratic flatness with subtle traces of red around the eyes, of blue shadow in the temples, with odd life in hair, jewels and lace–lace a little universe in itself, melting away to nothing at the edges and tangling to thickets in its densest parts.

Perhaps the most astonishing fruit of Hilliard’s time in France is the recently discovered miniature of the young king Henri III which combines hieratic flatness with subtle traces of red around the eyes, of blue shadow in the temples, with odd life in hair, jewels and lace–lace a little universe in itself, melting away to nothing at the edges and tangling to thickets in its densest parts.

The miniature above goes about as far as you can go in stretching the image to the frame, engorging the space completely, except where the hair takes over at the top, and on the right where the same ruff that lies flat against the background tilts upward, as if it has brushed against and been deflected by the wooden frame. This asymmetry, actually slight, is subtly disorienting, as if something within the image is moving, as the right-hand half of the picture becomes restive.

The miniature above goes about as far as you can go in stretching the image to the frame, engorging the space completely, except where the hair takes over at the top, and on the right where the same ruff that lies flat against the background tilts upward, as if it has brushed against and been deflected by the wooden frame. This asymmetry, actually slight, is subtly disorienting, as if something within the image is moving, as the right-hand half of the picture becomes restive.

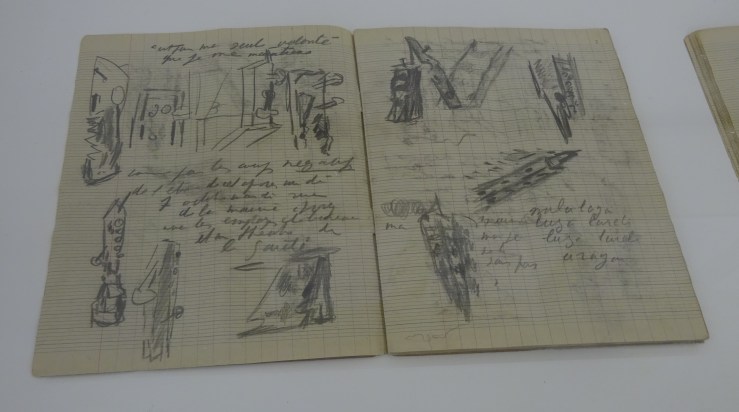

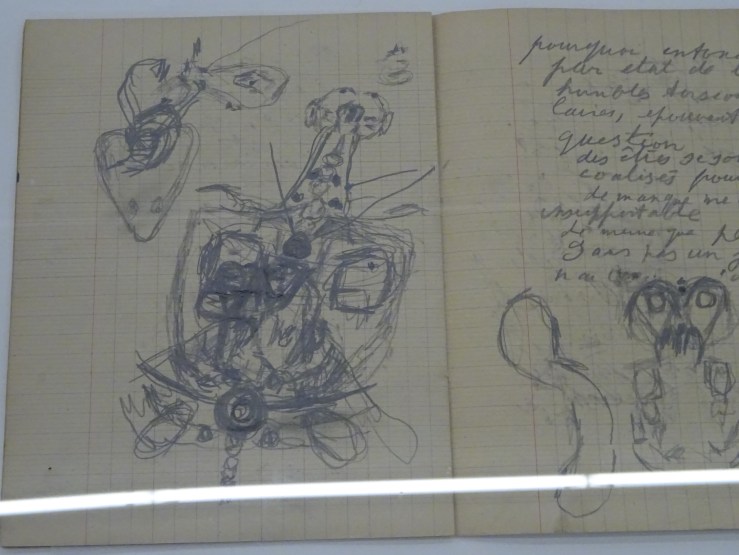

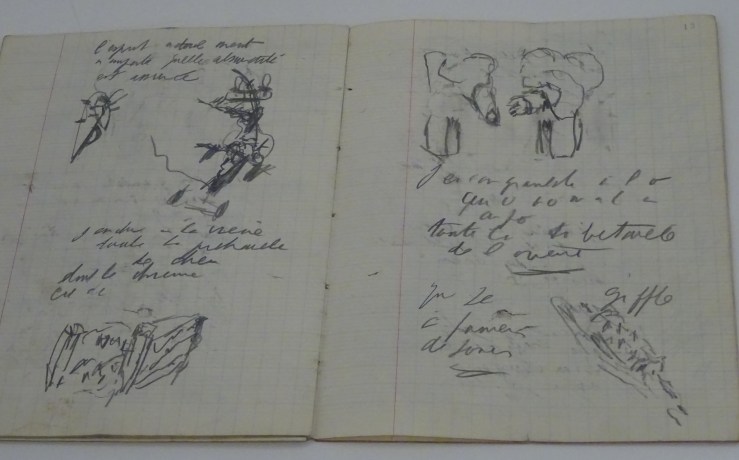

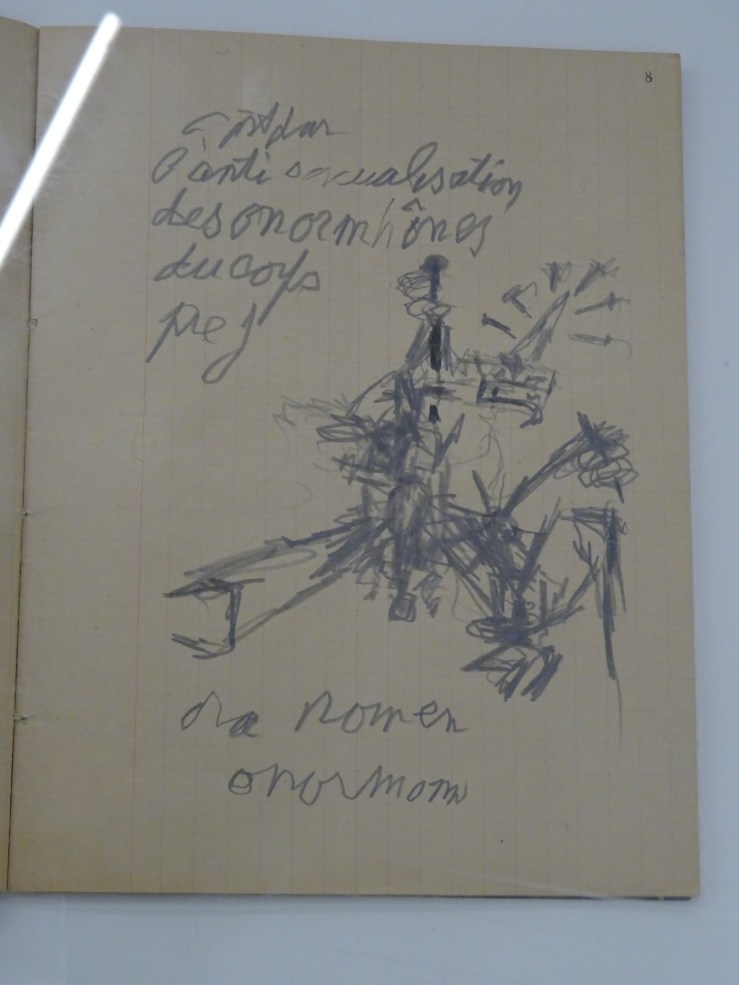

the intelligible never existed

one does not understand anything or learn anything

the intelligible never existed

one does not understand anything or learn anything

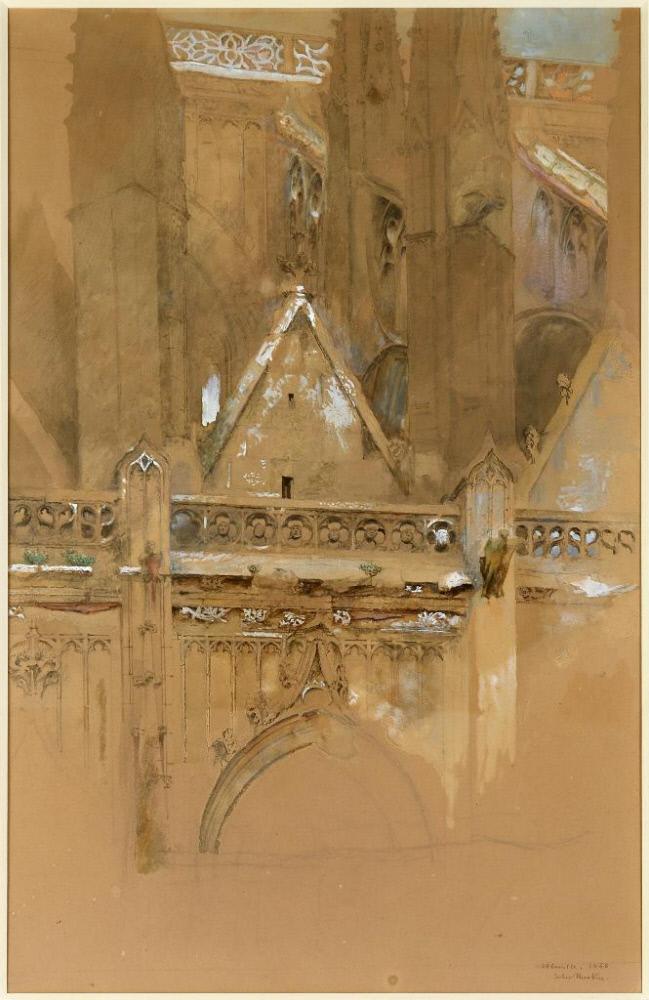

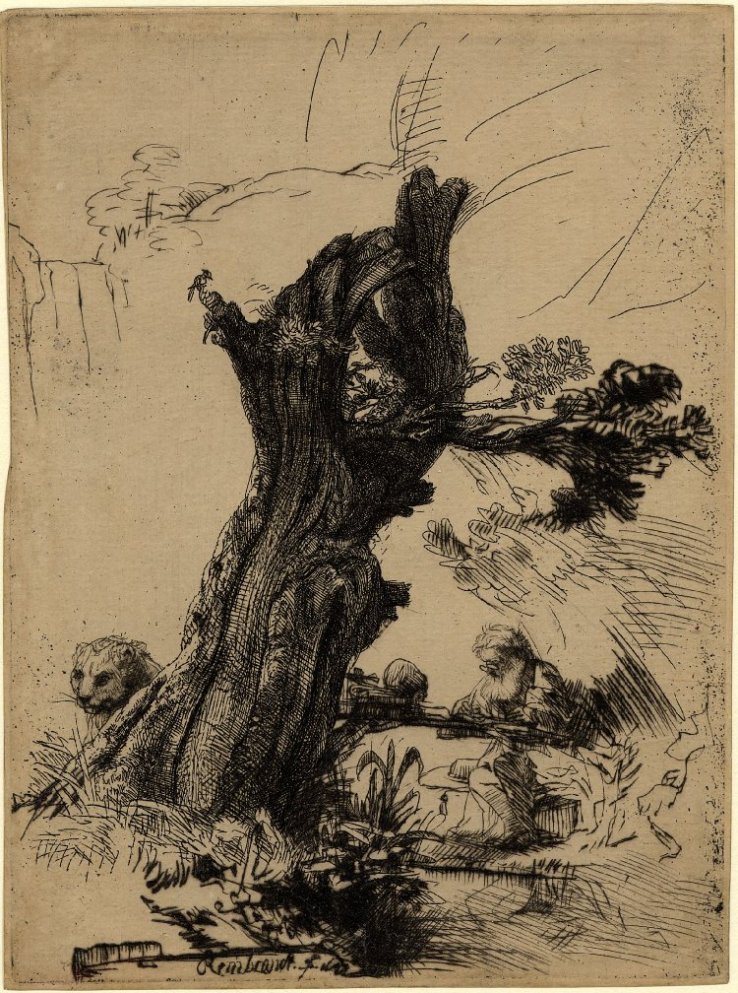

Ruskin’s strange boast ‘At least I did justice to the pine’ haunts me. He means ‘I may have failed, but at least I did justice to the pine’, ‘All the years I devoted to that enormous project, Modern Painters, were largely misspent, but at least….’

Ruskin’s strange boast ‘At least I did justice to the pine’ haunts me. He means ‘I may have failed, but at least I did justice to the pine’, ‘All the years I devoted to that enormous project, Modern Painters, were largely misspent, but at least….’

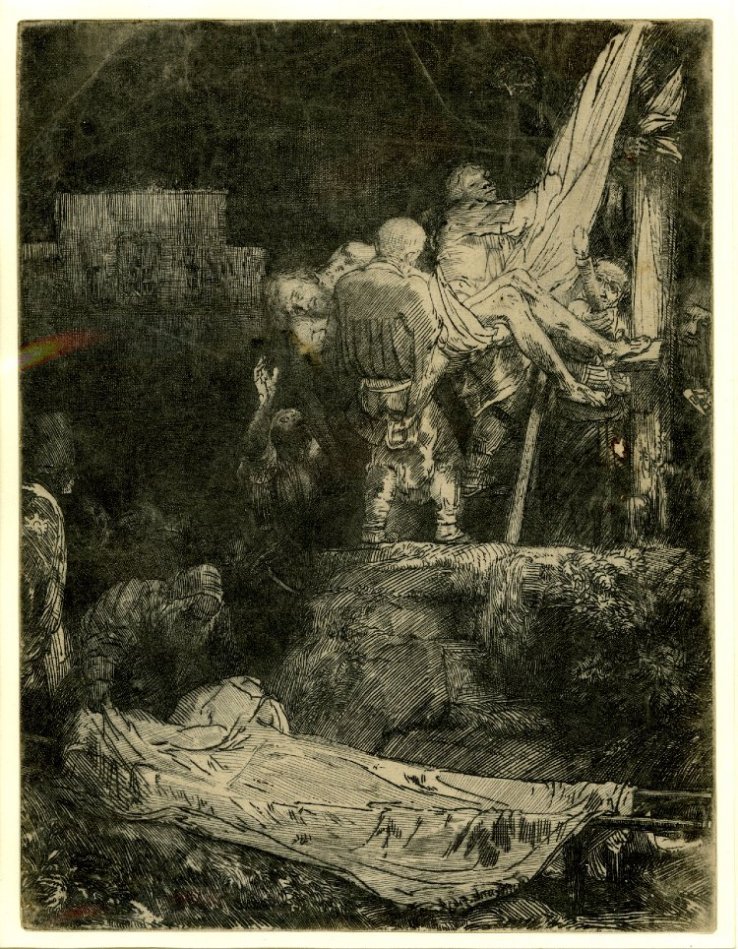

The darker Entombment in the British Museum exhibition has swallowed up its subject so completely you have to hallucinate it. There is a whole case of little prints like photos taken in a dark room. I felt I was being sent to a demanding school, but the rewards could be wonderful when they came. The best of them was a black nude with her back to you, lying on a white sheet with lace edges. The richness of these contrasts, the subtlety of all the shades of black seen in darkness, the startling whiteness with its delicate inscriptions jumping out from under blackness—to find something so luxurious just exactly here, such paradoxes, such depths.

The darker Entombment in the British Museum exhibition has swallowed up its subject so completely you have to hallucinate it. There is a whole case of little prints like photos taken in a dark room. I felt I was being sent to a demanding school, but the rewards could be wonderful when they came. The best of them was a black nude with her back to you, lying on a white sheet with lace edges. The richness of these contrasts, the subtlety of all the shades of black seen in darkness, the startling whiteness with its delicate inscriptions jumping out from under blackness—to find something so luxurious just exactly here, such paradoxes, such depths.

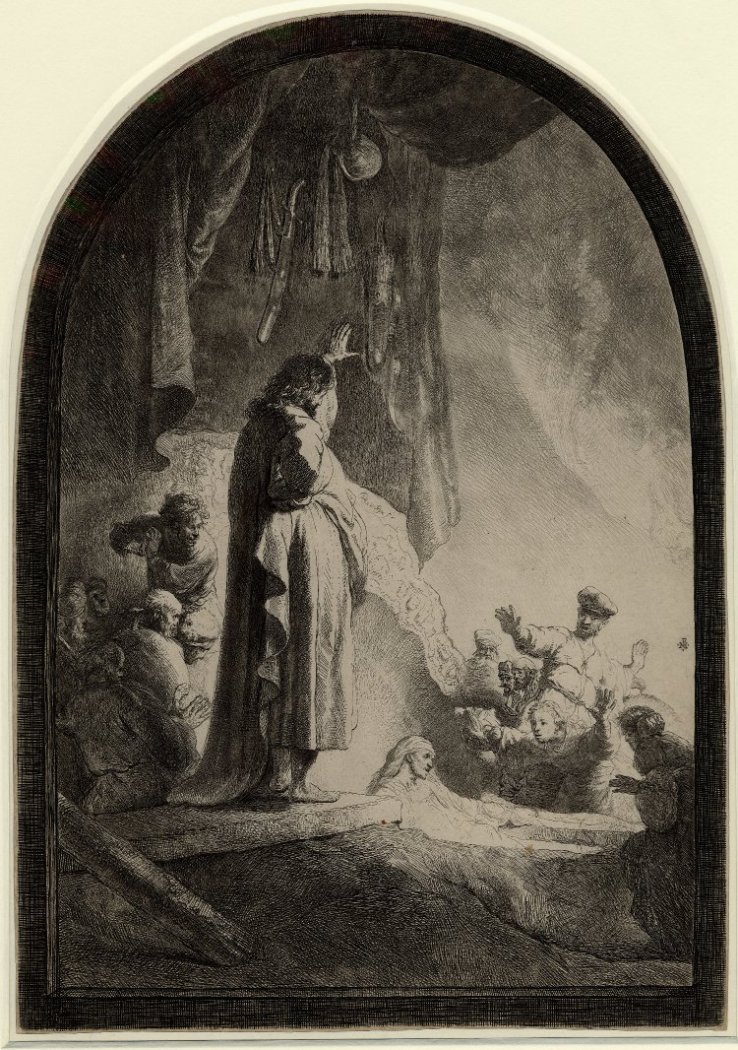

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically.

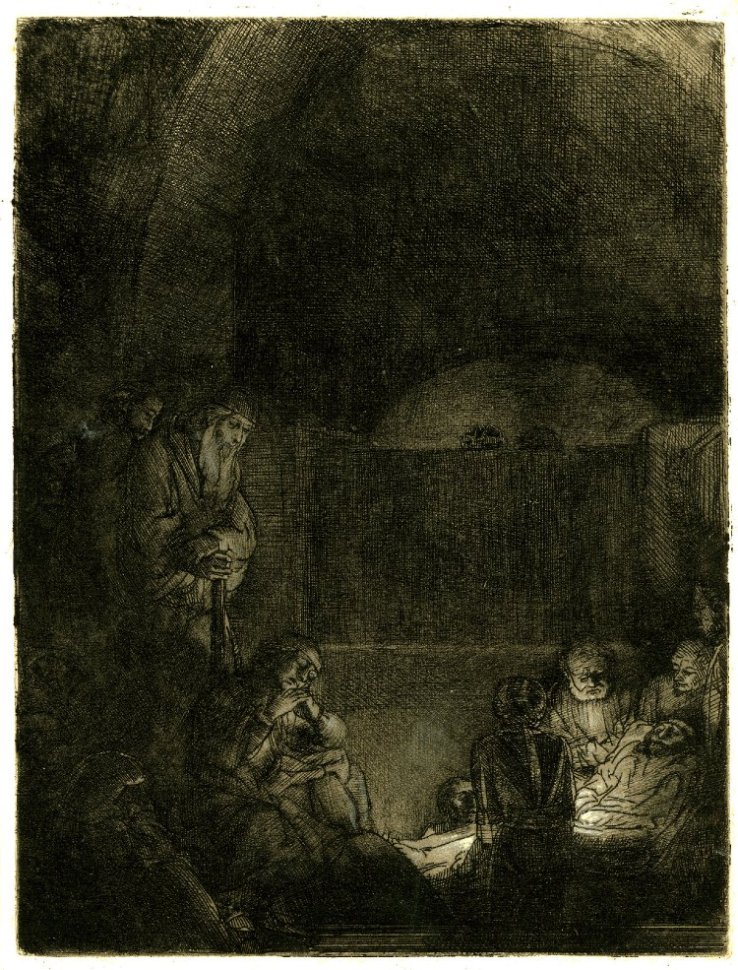

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically. Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Then

Then

In this species blooms often present themselves ‘upside down’ or cockeyed, meaning that to experience their symmetry or to recognise the typical orchid structure of three petals overlaid (in reverse) on three sepals, making a six-pointed figure, you need to reorient yourself bodily, and this leads us to imagine insects making aesthetic choices as they land on orchids.

In this species blooms often present themselves ‘upside down’ or cockeyed, meaning that to experience their symmetry or to recognise the typical orchid structure of three petals overlaid (in reverse) on three sepals, making a six-pointed figure, you need to reorient yourself bodily, and this leads us to imagine insects making aesthetic choices as they land on orchids.

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.