Ruskin is the most sublime and in his visionary way the most practical of the great Victorian thinkers. To call him just a thinker or a writer is a drastic truncation of his scope. He is the greatest writer on art in English, and he is also a great artist who left behind many hundreds of electrifying drawings of architecture, townscape, landscape and all aspects of the natural world, which have the potential to wake up human vision in a life-changing way, but remain to this day virtually unknown and seriously undervalued.

He was a mass of fertile contradictions whose life took a strange turn from the 1860s onward—the ‘violent Tory of the old school’ (a self-description) became a radical socialist (or should one more cautiously say, the inspirer of socialists?) whose greatest work (so Tim Hilton his most serious biographer believes) is an unruly series of ‘Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain’—that is the subtitle. In its title proper, this book communicates Ruskin-fashion via a kind of incantation—it’s called Fors Clavigera.

A recent exhibition, which began in London in February and continues in Sheffield from 29 May, focuses on a single visionary scheme for changing all that Ruskin thought was unhealthy about the rapidly industrialising country in which he found himself. This was a plan to bring beauty to one of the most benighted of the mushroom industrial towns of England by forming a quasi-medieval Guild of St George, consisting of Companions (workers) under a Master (himself), and endowing it with a collection of paintings, drawings, casts of sculpture, natural specimens (gems, shells, minerals, birds’ feathers), illuminated manuscripts and books, which would be the means by which impoverished toilers would educate themselves, becoming an example which could spread to other deprived areas and eventually regenerate the entire country.

Ruskin’s own method in his books and drawings was intensely particular, maniacally focused on the physical presence of the Gothic cathedral or Alpine peak, pursued with a fierce and sustained attention never equalled by anyone else before or since.

To make such absorption in the greatest architecture, painting, sculpture and geological and botanical marvels possible in Sheffield, Ruskin had to bring Venice and the Alps, and Dürer and Carpaccio into the little rooms he’d acquired for the purpose in a nondescript street in Walkley, then on the edge of the city.

As anyone who knows his writing might have predicted, his means of achieving this was emphatically literal. The exhibition is most interesting for showing how Ruskin’s various methods collided with and reinforced each other. The goals remained the same; the routes for getting there were diverse and overlapping. One of Ruskin’s favourite methods, taking plaster casts of architectural details, seems quaint and old-fashioned now, but had been important to him from long before he ever thought of using it to instruct the workers of Sheffield. It was a way of hanging onto buildings he had to leave behind in Italy, a way of bringing back some of the most powerful bits of carving to be studied and absorbed at home. He had always singled out details in a way of his own, had turned figures inhabiting the arcades of the Doge’s Palace into his familiar companions, for whom he elaborated characters, traits and lives. It was a gift that could get out of hand. He had always been haunted by figures he met in art: eventually they populated his deliriums.

Some of the most moving inclusions in the exhibition are the plaster fragments of St Mark’s in Venice, little bosses with birds and berries, and a large figure of Prudence from the central portal’s arch which would normally sit high over your head. Now it has its own case with a glass door, in which it is mounted crookedly, because it is a curving piece extracted from a larger whole, so its truncation is significant, the clearest sign that it has been singled out by Ruskin’s vision. But it remains ungainly, really too large to be turned into this kind of ornament, and obscured by the mechanism needed to mount it as a display. Yet when you get closer you see the point, the intensely three-dimensional presence of carving that has its own interior spaces, which constitute momentarily its own vineyard or forest whose thrust-out elements modulate the light in places further within.

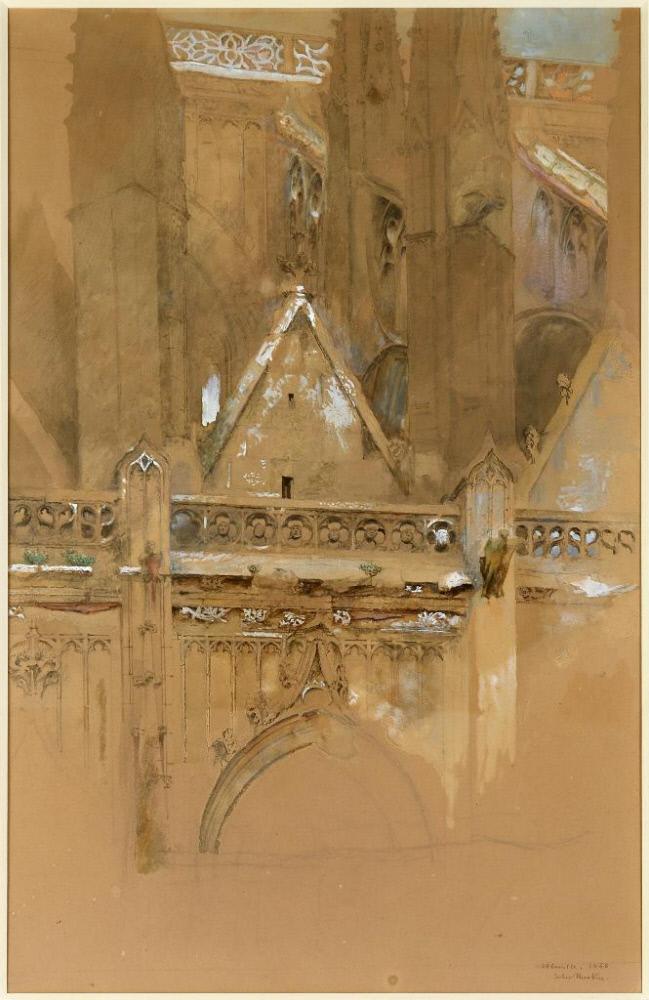

Ruskin’s drawings of architectural details are among his most magical; these are under-represented in the exhibition, but there is a compensation, a selection of photographs commissioned or taken by him, including a wonderful close-up of carved foliage on a doorframe at Rouen cathedral. Ruskin’s own vision does somehow miraculously inhabit the images of things he wanted recorded. In this case a wonderful drawing by him of the top furl in this image survives, which must have been taken from this photograph; it’s unlikely he would have singled out just that, standing on the ground.

This doorframe isn’t one of the most naturalistic bits of medieval vegetation, and we need to turn elsewhere to show how the connectedness of art and the natural world made itself felt to Ruskin. Art led him to study the growth of plants and the structure of mountains, but in the end which was the primary study, which a means to something else? Both the works of nature and of man occupied him wholly, and each continually illuminated the other. Ruskin’s famous drawing of withered oak leaves is one of the most striking in the exhibition, as is also the less familiar sketch of a spray of seaweed. Both of them are studies of rhythm and movement, strongly hinting at processes of decay and growth, and thus of life. His other botanical sketches also convey the tension in the bend of a stem or the torque implied by the disposition of separate thorns climbing the branch of the shrub. The thorn drawing looks boring at first, until one notices continual variation in what looked like sameness. This drawing isn’t Ruskin’s, but a task set by him to sharpen a student’s sight.

He trained a group of younger artists to help him record monuments and townscapes which he feared were disappearing through neglect and, even worse, so-called restoration. The most poignant of these rescue-drawings shows an unremarkable set of tombs built into a wall in a Florentine square. It’s a place many visitors will know well, now a heartless and dreary expanse of smooth stone, but in the drawing of 1887 a vibrant stretch of carving full of life, before more recent mechanical replacement.

Mountains, coins and birds’ feathers also appear in Ruskin’s drawings in the exhibition and include the ten-foot long horizontal profile of an Alpine range done when he was 24, and an analysis of a feather from a peacock’s back enlarged many times, entirely out of everyday recognition. Which brings me to the image at the top of the blog, an architectural detail enlarged so it could be seen from the back of the lecture hall, a close-up which looks blurred when you are too close to it.

The last word on mountains can be left to Dan Holdsworth, whose Acceleration of 2018 was an inspired commission by the organisers of the exhibition, combining many detailed records of three glaciers to make a video that lets you see them coming into existence and disappearing again, a new use for a new-old visual medium which would have delighted Ruskin.

John Ruskin: Art & Wonder 29 May to 15 September 2019 at Millennium Gallery, Museums Sheffield