What a moment to be broadcasting the USA as ‘the greatest country the world has ever known’, just one of a stream of boastful claims collected in a news story called The Last Days of Pompeo. Maybe there is a weird modesty in spreading this greatness over a long period, not just the last four years, in which Trump has been MAGA, Making America Great Again, mainly by repeating this ugly made-up word and claiming so emphatically he was doing it, that millions of his people believe it, and are already prophesying that they will go to their graves thinking it, simultaneously insisting that it has been stolen from them.

It seems that the greatest president the world has ever known has driven them to an intensified sense of deprivation, not the expected satisfied fulfilment. It is turning out that his final monument will be the biggest ever Lost Election, a void more compelling and lasting than any of his earlier ‘achievements’.

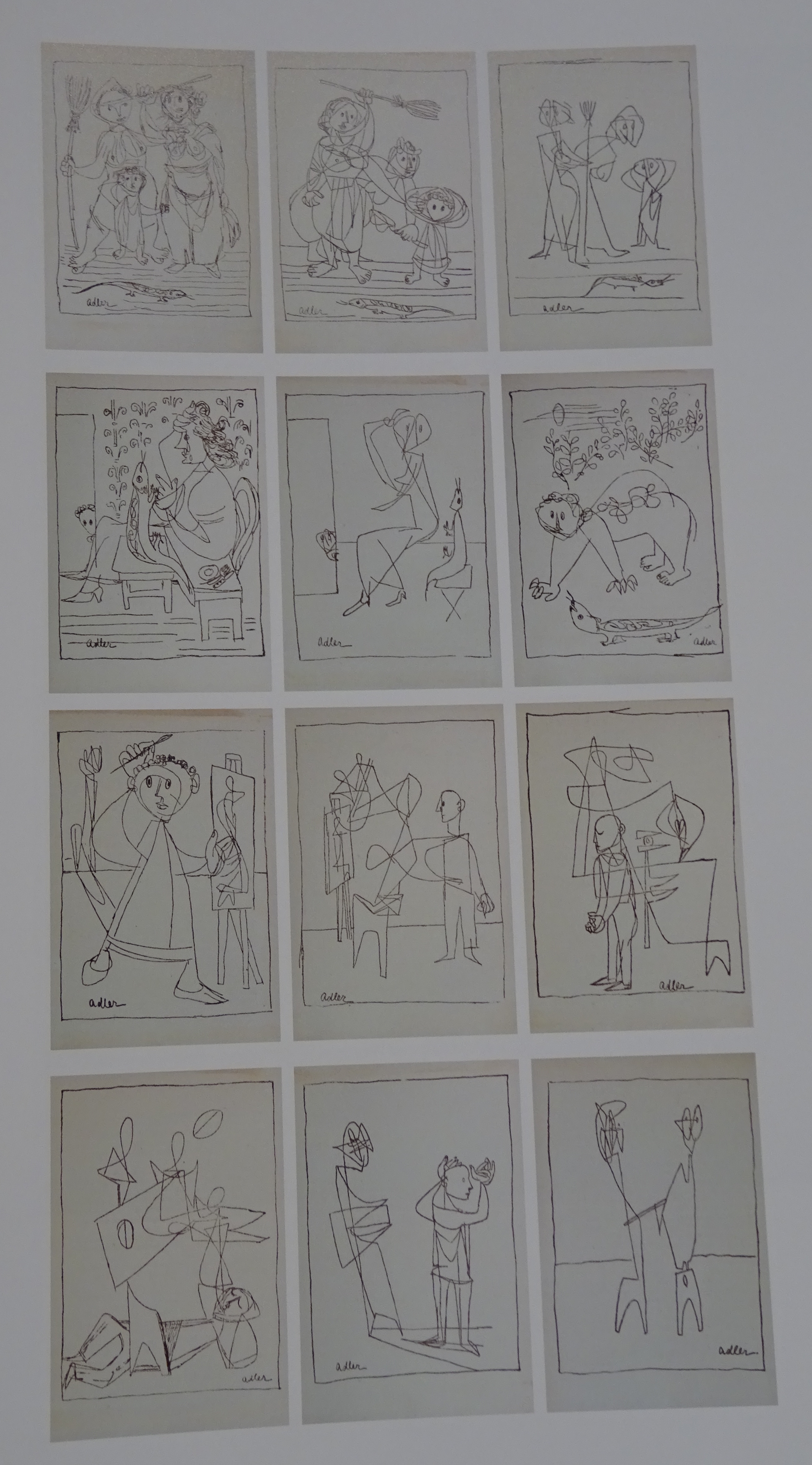

Which brings me to an alternative version of American Greatness or – more modestly – Struggle, a series of small images which set out to tell the whole history from Columbus to the First World War and then drew back to cover only the country’s first sixty years, from the 1770s to the war of 1812 and its aftermath.

The teller of this tale is Jacob Lawrence, the best known African American artist of another tormented era like our own, when the country wrestled with threats or fantasies of Communist subversion orchestrated by a persuasive demagogue, Senator Joseph McCarthy, and the violent/non-violent struggle of the early Civil Rights movement, offspring of the unfinished Civil War, the central subject of Lawrence’s narrative, though it never appears there directly, an event or battle that keeps rearing its head in our present as a beast who remains shockingly un-dead.

Before and after the Struggle series Lawrence was a devotee of pictorial narrative. Struggle is the most interesting and problematic of the ten series he eventually produced, partly by its tortuous circumstantial history, partly by its tricky subject matter. It began as the story of the Negro presence in the U.S. (the terminology, no longer acceptable, of the late 40s, early 50s when it was conceived), was expanded to include the history of all Americans, shrank again to end before the Civil War in large part because the first thirty images Lawrence produced did not sell. Is it fanciful to think that the series offers a more interesting challenge in its truncated form, where tensions seethe beneath the surface, seldom emerging in full view?

The American Struggle is Lawrence’s most interesting work because the influence of Cubism and Eisenstein’s montage, a filmic analogue to some of the distortions of Cubism, is both more glaring and more thoroughly digested than in his later work, so that radical formal experiment and urgent political material appear together, fused.

Lawrence spent a summer at Yaddo in 1954 when deep in planning, executing and naming the Struggle scenes. Here he became friends with Jay Leyda, a pupil of Eisenstein’s who had just finished his remarkable Melville Log, conceived as a birthday present for the Russian film-maker. This two-volume work was a piece of extreme formal experiment, a biography in the form of a collage, a collection of short bursts of vivid voices from Melville’s time, impinging in detail, cacophonous overall, requiring active untangling to make a comprehensible whole.

Leyda encouraged Lawrence in his preference for primary research in the Harlem branch library which had a notable collection of Black history material. They collaborated in finding titles for Lawrence’s scenes that were fragments of longer texts, of which the titles gave a flavour, suggesting that each subject had a literary existence in parallel with its visual self.

Like the Melville Log, Lawrence’s American Struggle would be a work actively materialised from fragments by the viewer. Like early Cubist constructions, the Struggle scenes sometimes don’t make complete sense initially. Looking at them is almost a muscular form of study, taking them apart in order to understand how they go together.

Many of the scenes seem increasingly violent the better you know them. But there may be a simpler explanation. The first time I looked through the images after the riots at the Capitol in Washington on 6 January 2021, I saw them as nothing but clashing blades and forests of weaponry. Maybe this only means that that element is there if you are susceptible to finding it, or in a state given to imagining conflict everywhere.

In the fifth image in the series, the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, one of the most traditional subjects, blades are legion. Sometimes they are knives, but they can just as well be shafts and glimmers of light, bits of the horse’s bridle, cactus-like leaves of low-growing plants, even (forms I can’t find other ways of interpreting) a walrus’s tusks.

However long you look, however successfully you dissect the composite forms, they still revert to their strong clumping after your back is turned, like the triangular mass of figures wailing and defending themselves upper left in scene 2 (Boston Massacre), who resemble the damned in representations of Hell, or the cyclonic funnel rushing down to the left in scene 4 (Paul Revere’s Ride). The clumping is not really intelligible but it is undeniably there, a force overriding whatever we might think.

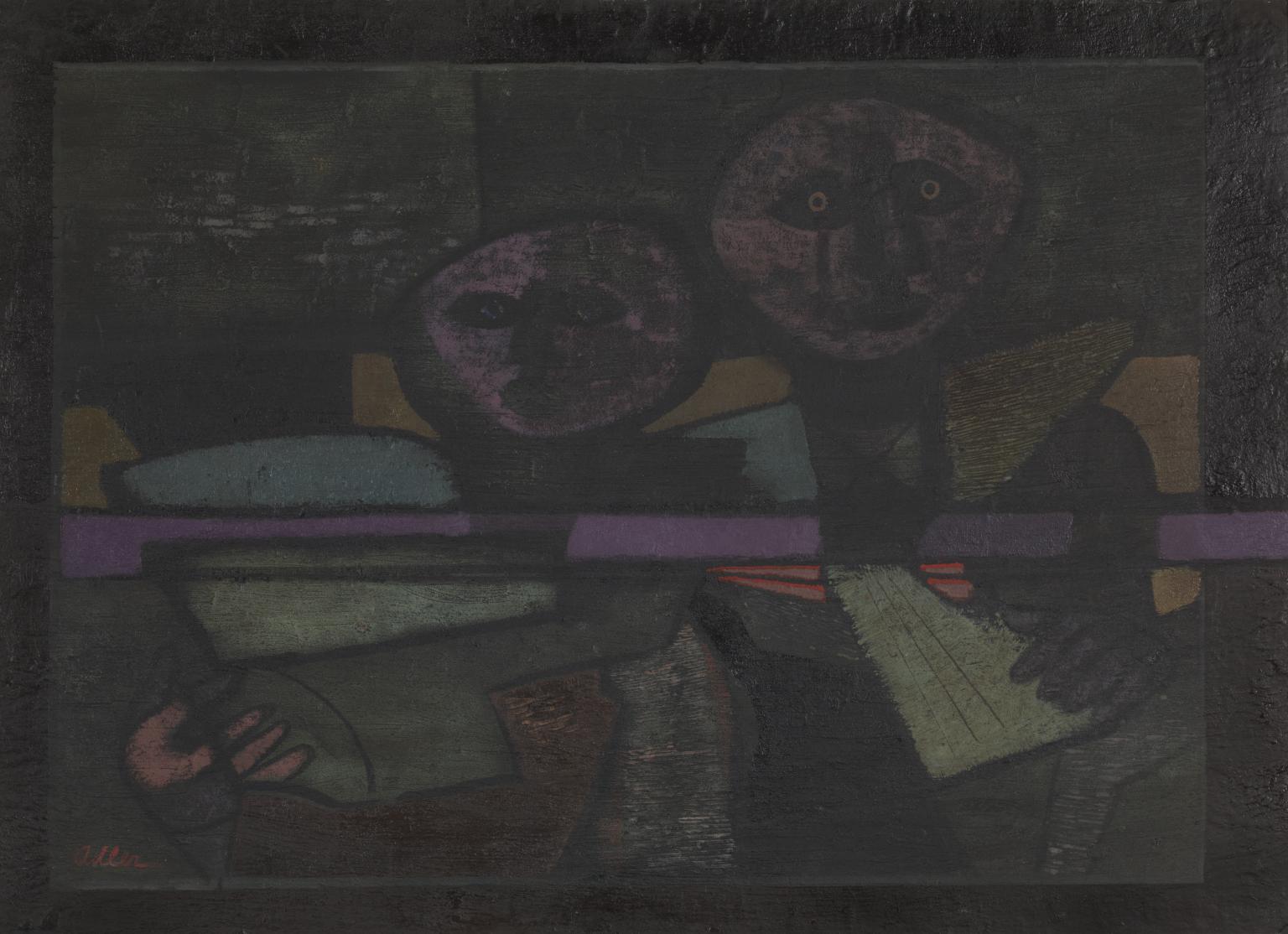

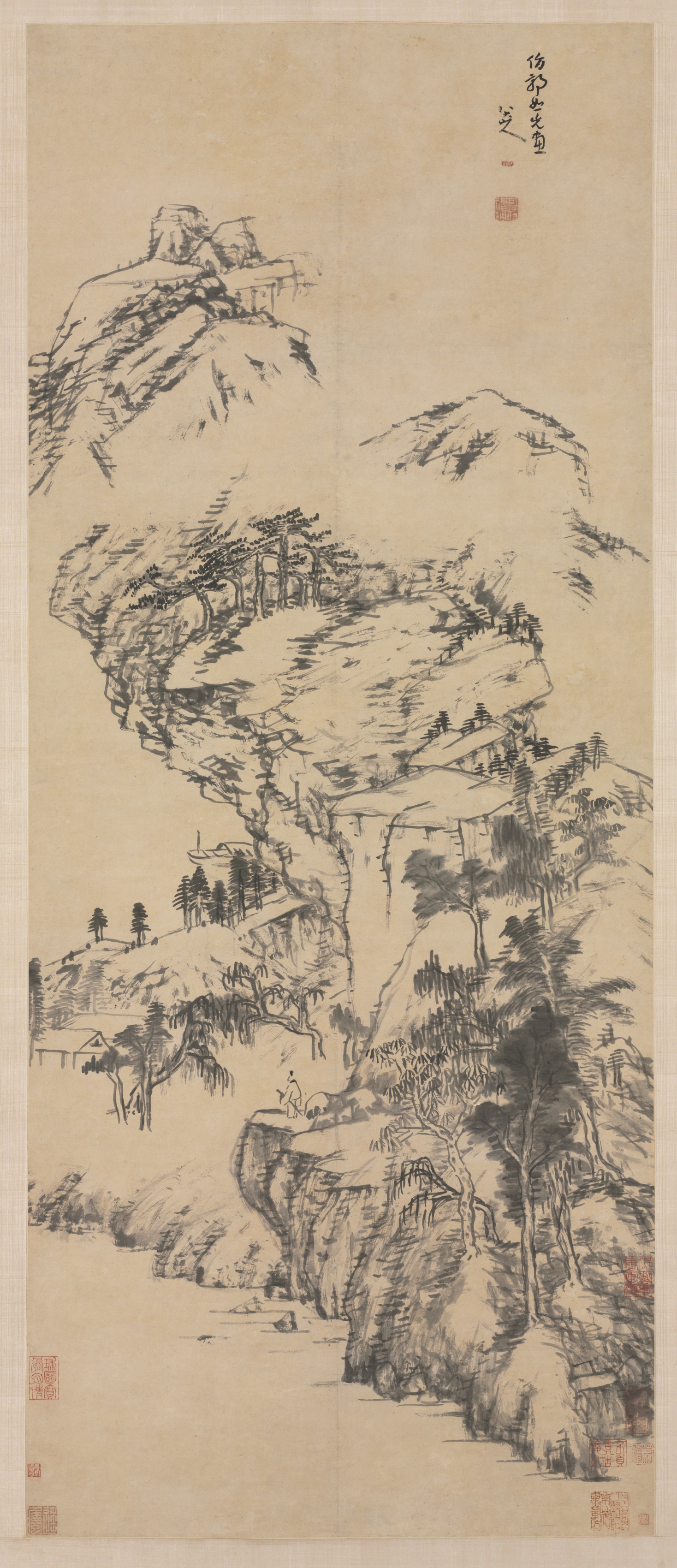

The next scene is the first vertical design in the series (see opening image), the most complete congestion or the most complex construction and the most obscure subject, A Petition by a slave named Felix which doesn’t look like the delivery of a piece of paper, as the first scene of all (Patrick Henry’s famous speech, which sparked the rebellion) doesn’t look like an event in a legislative hall, but among the damned in Hell (again), or Moses in Egypt (‘Let my people go’) . The room is on fire, the wall is bleeding, the audience is beside itself and making threatening gestures in every direction. The influence of Cubism is strong but obscure, more like a mask or veil for deep feeling than a means of direct expression. Raised fists are everywhere, but detached from their owners, just a bunched motif (see second image above).

The familiar scenes, known by schoolchildren, are few and far between and invariably unrecognisable in Lawrence’s versions. Like, above all, Washington Crossing the Delaware, a man in a fancy uniform standing up in a boat nearing the shore, of which my copy was so successful I was told to enlarge it in coloured chalk so that all the other children could enjoy it.

Did this really happen? In a literal sense, certainly not. It was a furtive achievement carried out at night, not a natural subject for paintings, unless like Lawrence you formed the drama out of the choppy water tossing the tippy boats, a thoroughly decentred scene, cut to pieces by the pervasive movement of warring oars and rifles, while any heroes kept themselves hidden.

The next great set piece, The Constitutional Convention, is usually shown as a crowd of little, stumpy figures congratulating themselves when the arguing is over. Lawrence concentrates on gear the delegates have taken off, their hats and coats, now a columned wall of shadows behind them, with their three-cornered hats as capitals. At the base, a spaghetti of discarded swords whose crinkled handles stand out. In the leftover slot across the middle of the scene two leaders in front are lying down like fallen heroes displayed in their coffins. Dense masses of delegates peep over them as over parapets. The leaders and two others languidly raise their arms to represent an exhausted vote. Drops of sweat stand out in everyone’s hair, replacing the displays of blood in the fighting. Is this the heroic tedium of democratic procedures, have swords been trampled into useful legislation, and could we claim we’ve converted barbarism to safety?

Another sword had lurched forth a little earlier, signifying another ambiguous end to conflict. It represents a cinematic close-up of the British commander Cornwallis admitting and denying defeat at once, signing the capitulation but refusing to give up his sword or attend the final ceremony. He cannot deny the loss but hangs onto the main symbol of aggression and absents himself at the last moment, cancelling his own reality and leaving a legal vacuum. Scene 13 Yorktown expresses the surreality of this attempt to deny full closure. The hallucinatory wall of twenty-two cannonballs corresponds to the days of the American siege, and above them the open hand of the law meets the closed fist of hollow defiance.

Lawrence is notably alert to cross currents in the story. Perhaps the only element more tortuous than the Black role in American life is that of Native Americans, one of the most ambiguous threads running through Lawrence’s narrative, never straightforward, ever more unnerving than we guess to begin with. Native Americans first appear as a convenient disguise for rebellious colonists dressed up as Indians to licence wild behaviour in the Boston Tea Party, a conceit adopted two hundred years later by radical right-wingers to push a corporatist agenda popular only in the most twisted sense: government itself is the enemy.

Lawrence’s Boston Tea Party is a kind of chaos, rebels and guards locked in a pinwheel in which it is impossible to pin down the participants. Forces of the law are reduced to enormous forearms which grab hold of Indians’ mask-like faces. We side with the Indians of course, their opponents don’t even have faces, but neither do the ‘Indians’, yet their painted-on masks and decoy-feathers seem more human and authentic than their opponents’ entire absence of characteristics. To all the scenes where they occur, the Indians bring colour and the jitter of movement. They embody sensory richness and the poignancy of choosing the wrong side – towards the end the great Indian orator Tecumseh repays the deception of treaty-breaking colonists by joining the British in the War of 1812. Another tangle like the Tea Party, seen from the other side. The powerful ox-blood-coloured skin of the Indians is set against the jangly baby-blue and white uniforms of the Americans. Now who was more authentically the keeper of the land?

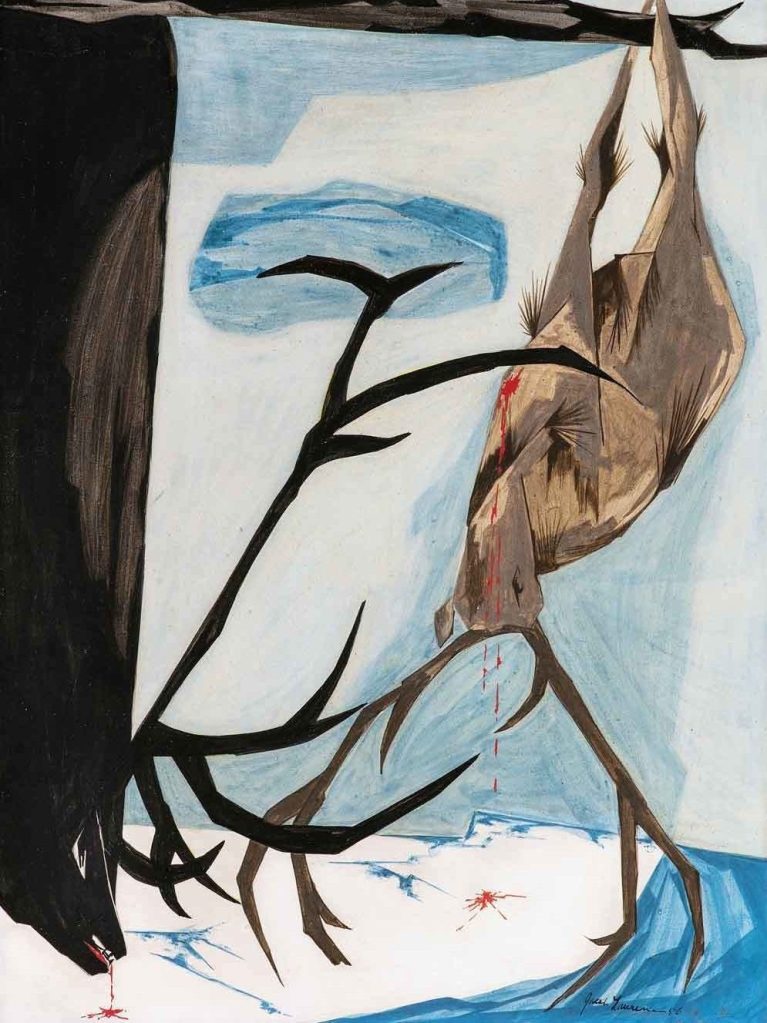

Among the most poignant later scenes are a few from which human populations are missing, above all the scene called Nez Perce after the native trail across the northern limits of the country, which records another vanished population, the plentiful wild life that the various processes of human civilisation, both the fur trade and agriculture, will eventually crowd out.

This composition is dominated by a misshapen crown of thorns made of the antler racks of two different species of elk strung up against an icy Arctic background. The result is a scene both war-like and tranquil. It is hard to believe at first that all the linear excitement belongs to the two animals and not to a larger force or idea.

The main lines of American expansion over seemingly endless expanses are buried here and there in Lawrence’s narrative, in Jefferson’s humanist project of exploration, concealing a strong appetite for dominance in a manipulative tolerance of natives that is crystallised in a telling instance. An Indian woman given a job as an interpreter is thrown into contact with a long-lost brother now a chief with whom she is expected to negotiate, a rapturous reunion overshadowed by the white man’s bureaucracy.

Lawrence shows old totems intact but it seems more likely one or both of the natives has been corrupted into different mindsets by contact with white men. Maybe the strongest hint that all is not well are the primitive rigidities of all the figures here, native brother and sister, and the white technicians, momentarily on the fringes of the group.

The final scene with a missing population occurs when the series ends abruptly in a token image of the drive to settle the whole width of the continent. This takes the relatively harmless and unbelligerent form of two covered wagons, two oxen and no settlers, unless big blood drippings on one of the wagons stand for the settlers’ ordeal. Migration in various guises is the great subject of this phase of the nation’s growth, and Andrew Jackson, Trump’s favourite president, is the presiding genius of this section of Lawrence’s narrative. He only ‘appears’ once in the Struggle series, quoted but not shown, as the victor in the Battle of New Orleans, a decisive triumph at the end of the War of 1812. Technically the battle occurred after the Treaty of Ghent ending the war had been signed. In the time it took news that the war was over to arrive from Europe, the glorious triumph occurred, and Jackson’s reputation was made.

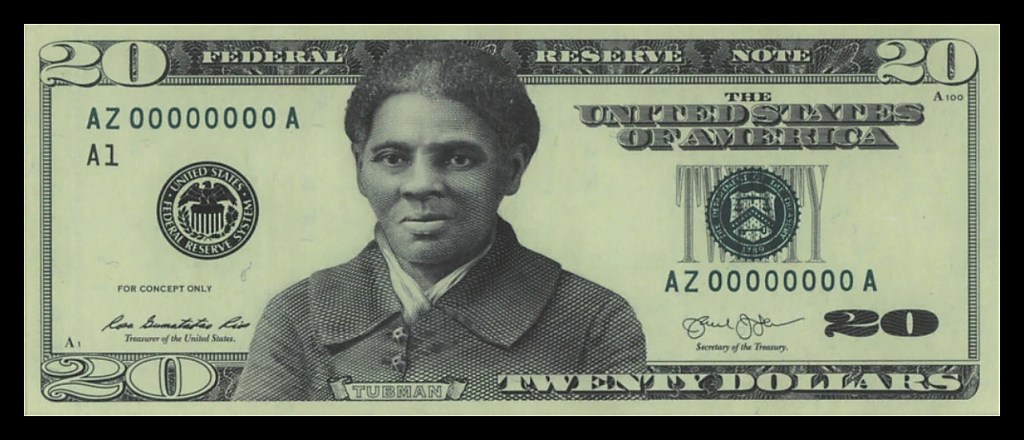

The scene representing the battle is the most inert in the series. Both sides are lifeless and exhausted, the Americans inside their fort at the top, the British lying crumpled beneath its wall at the bottom. Nonetheless, the pointless victory helped propel Jackson to the White House and the place most Americans know him from, the front of a twenty dollar bill.

Jackson’s greatest later claim to fame begins to seem less magnificent. It starts with ignoring a Supreme Court decision that treaties awarding territories in the southeastern United States to Native Americans are valid and must be honoured, and continues with masterminding the forced removal of 70,000 native Cherokees, Creeks, Seminoles, Chickasaws and Chocktaws from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Florida to Oklahoma. Conditions in the seasons chosen for the move were harsh and unhealthy. Imported European diseases, especially cholera, rampaged among the migrants. Matching or paralleling the movement of willing European migrants westward is the reverse migration of the uprooted tribes, deported against their will from land they knew and belonged in to another they didn’t recognise. It’s a less up-lifting tale than the usual epic of continued westward expansion, but the Trail of Tears, with many thousands of deaths on the journey and after, needs telling too.

Thomas Jefferson, rightly revered for many reasons, played a limited but crucial role in stripping Native Americans of lands and rights. In 2020 there were cries in some quarters for tearing down the Jefferson Memorial in the centre of Washington, mainly I think for his role as a slave owner and an abuser of one of his female slaves in particular.

As a child I thought the Jefferson Memorial was one of the perfect things of the world. As an adult I came to like it and other works of its architect John Russell Pope (like the National Gallery of Art on the other side of the Mall) less unconditionally, for their sleek, almost moderne classicism, just one of the entertaining riffs later designers have played on Roman themes.

At the time of these demolition proposals it seemed to me that instead of tearing the Memorial down you could incorporate a memorial to Harriet Tubman in or beside or near the present one to Jefferson. This seemed a better idea than just substituting a Tubman Memorial. Of course their lives didn’t overlap, but Tubman took brave steps to realise some of Jefferson’s ideals more practically than he ever found a way to do, so they belong together in a real sense, and there are sculptors/architects/artists who could express this continuity which would make his Memorial more meaningful than it is for some at the moment. The new elements needn’t impinge grotesquely on the old, but they might.

Andrew Jackson was also due to encounter Harriet Tubman, but then Trump was elected and the meeting was cancelled or kicked into the long grass. Jackson was set to be replaced on the twenty-dollar bill by Tubman, when Trump’s Secretary of the Treasury put it off until 2028 ‘for technical reasons’. Now might be a good time to resurrect this idea and put a woman, a black woman and a former slave on American money at last.

Exploring the picture is again analogous to getting used to seeing in the dark. It can be a long process, working out various relations in this composition, which intrigues us so much because it is so unclear. It’s another subject showing, like the Death of the Virgin, people gathered round a prone figure, a quintessentially static subject.

Exploring the picture is again analogous to getting used to seeing in the dark. It can be a long process, working out various relations in this composition, which intrigues us so much because it is so unclear. It’s another subject showing, like the Death of the Virgin, people gathered round a prone figure, a quintessentially static subject.

![34 ptg twombly untitled [say goodbye catullus to the shores of asia minor]1994 room w huge mural menil houston.jpg](https://robertharbisonsblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/34-ptg-twombly-untitled-say-goodbye-catullus-to-the-shores-of-asia-minor1994-room-w-huge-mural-menil-houston.jpg)

The work consists of another steep ascent and precipitous fall. A slender frame contains an exuberantly molten platform-mound of plaster heaving with life, but the overall impression is something like a guillotine waiting to descend. The childish quality of Twombly’s inscribings makes me think of a-semic writing, writing that looks like words but isn’t, a mode with which Twombly filled whole canvases in certain phases of his career.

The work consists of another steep ascent and precipitous fall. A slender frame contains an exuberantly molten platform-mound of plaster heaving with life, but the overall impression is something like a guillotine waiting to descend. The childish quality of Twombly’s inscribings makes me think of a-semic writing, writing that looks like words but isn’t, a mode with which Twombly filled whole canvases in certain phases of his career.

He is so shrouded in gilded paraphernalia that he ceases to seem much like a being of flesh and blood, if it weren’t for a few contrary traces. He is clean-shaven but there are signs that his beard is growing, silver stubble just beginning to show on his cheeks. And the six tiny statues (Virtues rather than the saints whom we expect) in little niches on ether side of his throne are fully coloured and demonstratively in motion. In the most extreme case, Temperance is pouring from a pitcher, and Bermejo has run together the dark colour of her cloak and a dark blot like a dragon’s tail on the saint’s cope, part of a pattern on the garment that is mostly hidden from us. So we are invited to imagine a spreading stain originating in an inadvertent spillage of Temperance’s remixed wine.

He is so shrouded in gilded paraphernalia that he ceases to seem much like a being of flesh and blood, if it weren’t for a few contrary traces. He is clean-shaven but there are signs that his beard is growing, silver stubble just beginning to show on his cheeks. And the six tiny statues (Virtues rather than the saints whom we expect) in little niches on ether side of his throne are fully coloured and demonstratively in motion. In the most extreme case, Temperance is pouring from a pitcher, and Bermejo has run together the dark colour of her cloak and a dark blot like a dragon’s tail on the saint’s cope, part of a pattern on the garment that is mostly hidden from us. So we are invited to imagine a spreading stain originating in an inadvertent spillage of Temperance’s remixed wine.