Ruskin is the most sublime and in his visionary way the most practical of the great Victorian thinkers. To call him just a thinker or a writer is a drastic truncation of his scope. He is the greatest writer on art in English, and he is also a great artist who left behind many hundreds of electrifying drawings of architecture, townscape, landscape and all aspects of the natural world, which have the potential to wake up human vision in a life-changing way, but remain to this day virtually unknown and seriously undervalued.

He was a mass of fertile contradictions whose life took a strange turn from the 1860s onward—the ‘violent Tory of the old school’ (a self-description) became a radical socialist (or should one more cautiously say, the inspirer of socialists?) whose greatest work (so Tim Hilton his most serious biographer believes) is an unruly series of ‘Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain’—that is the subtitle. In its title proper, this book communicates Ruskin-fashion via a kind of incantation—it’s called Fors Clavigera.

A recent exhibition, which began in London in February and continues in Sheffield from 29 May, focuses on a single visionary scheme for changing all that Ruskin thought was unhealthy about the rapidly industrialising country in which he found himself. This was a plan to bring beauty to one of the most benighted of the mushroom industrial towns of England by forming a quasi-medieval Guild of St George, consisting of Companions (workers) under a Master (himself), and endowing it with a collection of paintings, drawings, casts of sculpture, natural specimens (gems, shells, minerals, birds’ feathers), illuminated manuscripts and books, which would be the means by which impoverished toilers would educate themselves, becoming an example which could spread to other deprived areas and eventually regenerate the entire country.

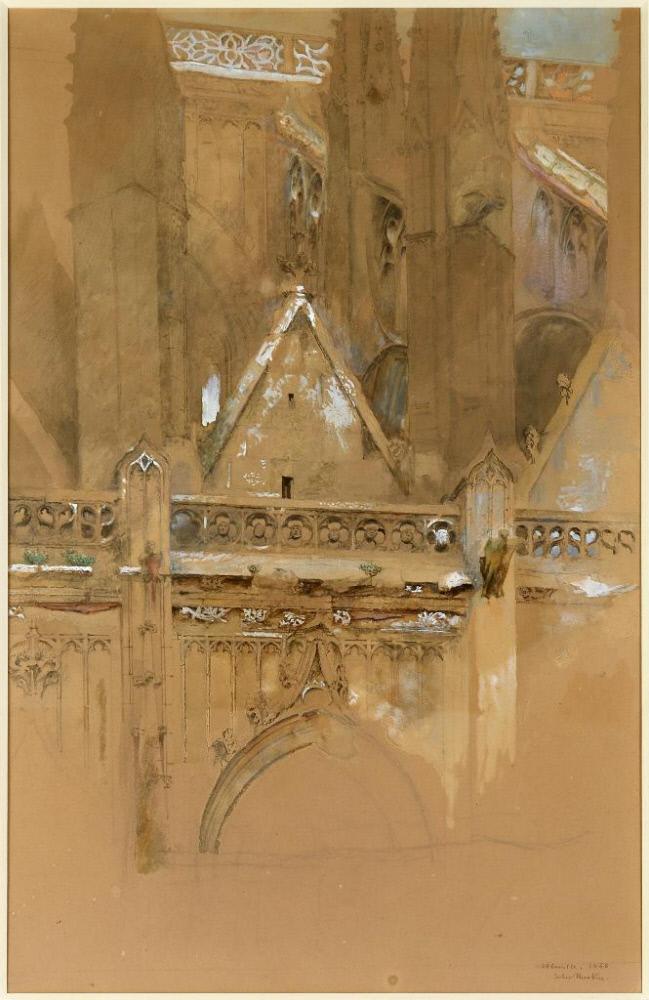

Ruskin’s own method in his books and drawings was intensely particular, maniacally focused on the physical presence of the Gothic cathedral or Alpine peak, pursued with a fierce and sustained attention never equalled by anyone else before or since.

To make such absorption in the greatest architecture, painting, sculpture and geological and botanical marvels possible in Sheffield, Ruskin had to bring Venice and the Alps, and Dürer and Carpaccio into the little rooms he’d acquired for the purpose in a nondescript street in Walkley, then on the edge of the city.

As anyone who knows his writing might have predicted, his means of achieving this was emphatically literal. The exhibition is most interesting for showing how Ruskin’s various methods collided with and reinforced each other. The goals remained the same; the routes for getting there were diverse and overlapping. One of Ruskin’s favourite methods, taking plaster casts of architectural details, seems quaint and old-fashioned now, but had been important to him from long before he ever thought of using it to instruct the workers of Sheffield. It was a way of hanging onto buildings he had to leave behind in Italy, a way of bringing back some of the most powerful bits of carving to be studied and absorbed at home. He had always singled out details in a way of his own, had turned figures inhabiting the arcades of the Doge’s Palace into his familiar companions, for whom he elaborated characters, traits and lives. It was a gift that could get out of hand. He had always been haunted by figures he met in art: eventually they populated his deliriums.

Some of the most moving inclusions in the exhibition are the plaster fragments of St Mark’s in Venice, little bosses with birds and berries, and a large figure of Prudence from the central portal’s arch which would normally sit high over your head. Now it has its own case with a glass door, in which it is mounted crookedly, because it is a curving piece extracted from a larger whole, so its truncation is significant, the clearest sign that it has been singled out by Ruskin’s vision. But it remains ungainly, really too large to be turned into this kind of ornament, and obscured by the mechanism needed to mount it as a display. Yet when you get closer you see the point, the intensely three-dimensional presence of carving that has its own interior spaces, which constitute momentarily its own vineyard or forest whose thrust-out elements modulate the light in places further within.

Ruskin’s drawings of architectural details are among his most magical; these are under-represented in the exhibition, but there is a compensation, a selection of photographs commissioned or taken by him, including a wonderful close-up of carved foliage on a doorframe at Rouen cathedral. Ruskin’s own vision does somehow miraculously inhabit the images of things he wanted recorded. In this case a wonderful drawing by him of the top furl in this image survives, which must have been taken from this photograph; it’s unlikely he would have singled out just that, standing on the ground.

This doorframe isn’t one of the most naturalistic bits of medieval vegetation, and we need to turn elsewhere to show how the connectedness of art and the natural world made itself felt to Ruskin. Art led him to study the growth of plants and the structure of mountains, but in the end which was the primary study, which a means to something else? Both the works of nature and of man occupied him wholly, and each continually illuminated the other. Ruskin’s famous drawing of withered oak leaves is one of the most striking in the exhibition, as is also the less familiar sketch of a spray of seaweed. Both of them are studies of rhythm and movement, strongly hinting at processes of decay and growth, and thus of life. His other botanical sketches also convey the tension in the bend of a stem or the torque implied by the disposition of separate thorns climbing the branch of the shrub. The thorn drawing looks boring at first, until one notices continual variation in what looked like sameness. This drawing isn’t Ruskin’s, but a task set by him to sharpen a student’s sight.

He trained a group of younger artists to help him record monuments and townscapes which he feared were disappearing through neglect and, even worse, so-called restoration. The most poignant of these rescue-drawings shows an unremarkable set of tombs built into a wall in a Florentine square. It’s a place many visitors will know well, now a heartless and dreary expanse of smooth stone, but in the drawing of 1887 a vibrant stretch of carving full of life, before more recent mechanical replacement.

Mountains, coins and birds’ feathers also appear in Ruskin’s drawings in the exhibition and include the ten-foot long horizontal profile of an Alpine range done when he was 24, and an analysis of a feather from a peacock’s back enlarged many times, entirely out of everyday recognition. Which brings me to the image at the top of the blog, an architectural detail enlarged so it could be seen from the back of the lecture hall, a close-up which looks blurred when you are too close to it.

The last word on mountains can be left to Dan Holdsworth, whose Acceleration of 2018 was an inspired commission by the organisers of the exhibition, combining many detailed records of three glaciers to make a video that lets you see them coming into existence and disappearing again, a new use for a new-old visual medium which would have delighted Ruskin.

John Ruskin: Art & Wonder 29 May to 15 September 2019 at Millennium Gallery, Museums Sheffield

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.

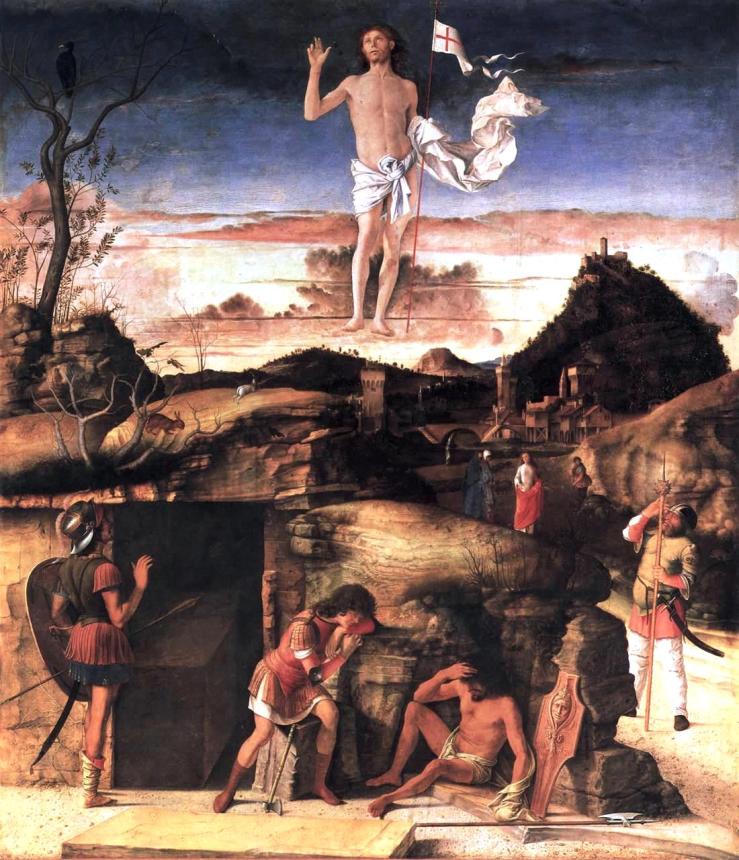

Two fascinating drawings stood in for the absent painting, one with the three Maries bent over the prone figure in something like the Milan position, with feet pointing toward the viewer (actually at c 25 degrees angled left). Then, most surprisingly, another Christ is included, pointing the other way, at the same deflection to the right. The two dead bodies are parallel and would touch if the one further away were not raised a foot off the ground the nearer body lies on. It verges on two bodies trying to inhabit the same space, or slotting together like a puzzle.

Two fascinating drawings stood in for the absent painting, one with the three Maries bent over the prone figure in something like the Milan position, with feet pointing toward the viewer (actually at c 25 degrees angled left). Then, most surprisingly, another Christ is included, pointing the other way, at the same deflection to the right. The two dead bodies are parallel and would touch if the one further away were not raised a foot off the ground the nearer body lies on. It verges on two bodies trying to inhabit the same space, or slotting together like a puzzle.

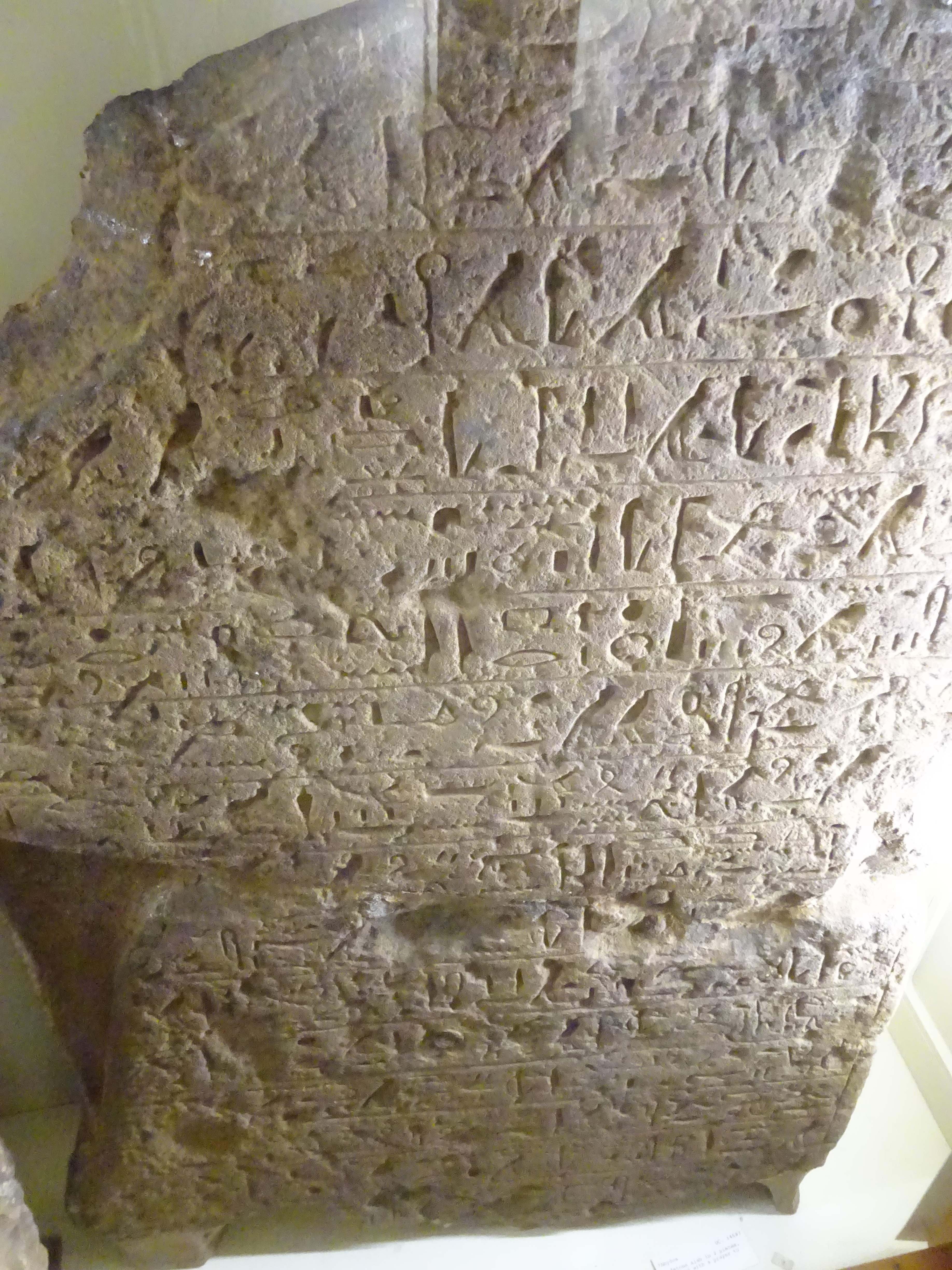

Museums are usually more accommodating, making you think you are getting somewhere, but here there’s no overarching narrative, only a tremendous crowd of separate things. I got the idea I should write about the Petrie in the first flush of my enthusiasm, preserving the exact state of my current ignorance, before I’d read any further in the two books I got there and found out more. This would give me a chance to test a favourite theory, according to which I’ll do damage by burdening myself with learning, like a burrowing animal going further into darkness.

Museums are usually more accommodating, making you think you are getting somewhere, but here there’s no overarching narrative, only a tremendous crowd of separate things. I got the idea I should write about the Petrie in the first flush of my enthusiasm, preserving the exact state of my current ignorance, before I’d read any further in the two books I got there and found out more. This would give me a chance to test a favourite theory, according to which I’ll do damage by burdening myself with learning, like a burrowing animal going further into darkness.

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of. In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving.

In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving. There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within.

There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within. In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

Its subjects exist outside history in a world ruled by metaphor, like a huge butterfly mask in Washington with four birds and three chameleons perched on it, stretching sideways for almost six feet in a shape unlike any face that ever was. Labels for such objects too often simply show the limits of knowledge—dates are the date it was collected, or a guess–‘late 19th/ early 20th century (?)’—how often have we met that? Then comes an interesting debate about which of two nearby groups is more likely as the source of the work. In the meantime more intriguing questions have slipped away—why a butterfly? why such an abstract, bird-like form of butterfly? why such strident tattooing over the whole wing-surface of the flimsy creature? and the inversions of size, small birds & large butterfly—is that just a picture of thought roaming free, or a more specific puzzle to be solved? No answers, only questions.

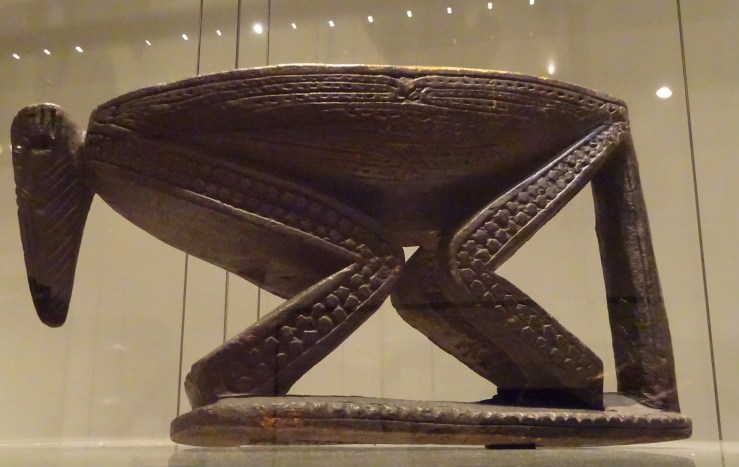

Its subjects exist outside history in a world ruled by metaphor, like a huge butterfly mask in Washington with four birds and three chameleons perched on it, stretching sideways for almost six feet in a shape unlike any face that ever was. Labels for such objects too often simply show the limits of knowledge—dates are the date it was collected, or a guess–‘late 19th/ early 20th century (?)’—how often have we met that? Then comes an interesting debate about which of two nearby groups is more likely as the source of the work. In the meantime more intriguing questions have slipped away—why a butterfly? why such an abstract, bird-like form of butterfly? why such strident tattooing over the whole wing-surface of the flimsy creature? and the inversions of size, small birds & large butterfly—is that just a picture of thought roaming free, or a more specific puzzle to be solved? No answers, only questions. Ordinary objects are turning into animals, like a stool ingeniously composed of a long nosed beast which can fold its limbs into a stool with none left over or sticking out, an improbable completeness in disparate realities aligned. Less immediately perplexing are appliances embellished with a single or a couple of animal features, a big container with a head and a tail, or a backrest with a ram’s head at the top and two supports turning into his front legs, the rest of him nowhere to be seen or thought of as continuing underground.

Ordinary objects are turning into animals, like a stool ingeniously composed of a long nosed beast which can fold its limbs into a stool with none left over or sticking out, an improbable completeness in disparate realities aligned. Less immediately perplexing are appliances embellished with a single or a couple of animal features, a big container with a head and a tail, or a backrest with a ram’s head at the top and two supports turning into his front legs, the rest of him nowhere to be seen or thought of as continuing underground. It is wrong to view the animal features as embellishments or decoration of a useful object. They are all we need to turn a thing into a being. Even a modern Westerner, susceptible enough to the literal mindedness that runs deep in all art, will seize on the slightest signs that the inanimate is becoming animate to take the hint, carry it further and complete the conversion, even in the case where what I took for a large storage container made from a log is actually a slit-drum for sending long-distance messages by banging on its sides with wooden hammers. I reckoned it a giant ant-eater, so stretched-out was its body, nine feet long, but everyone agrees that the head is another ram’s head, and the tail a ram’s tail, so these proportions call for difficult digesting by the viewer. Or perhaps its mass is so powerful that it overcomes all objections by that fact alone.

It is wrong to view the animal features as embellishments or decoration of a useful object. They are all we need to turn a thing into a being. Even a modern Westerner, susceptible enough to the literal mindedness that runs deep in all art, will seize on the slightest signs that the inanimate is becoming animate to take the hint, carry it further and complete the conversion, even in the case where what I took for a large storage container made from a log is actually a slit-drum for sending long-distance messages by banging on its sides with wooden hammers. I reckoned it a giant ant-eater, so stretched-out was its body, nine feet long, but everyone agrees that the head is another ram’s head, and the tail a ram’s tail, so these proportions call for difficult digesting by the viewer. Or perhaps its mass is so powerful that it overcomes all objections by that fact alone.

It isn’t really in the same class-–creating fear or disturbance—but the famous mask with twelve eyes might be in its way just as intimidating. The rules of ordinary reality give way all at once without a chance to discuss them. Of all the objects in this series, this is the one which most needs to be seen in isolation for full effect, surrounded by a void, a true minimalist reduction.

It isn’t really in the same class-–creating fear or disturbance—but the famous mask with twelve eyes might be in its way just as intimidating. The rules of ordinary reality give way all at once without a chance to discuss them. Of all the objects in this series, this is the one which most needs to be seen in isolation for full effect, surrounded by a void, a true minimalist reduction.

It is rare to find reliable reports connected with a specific piece. The History of Art in Africa illustrates a mask that resembles an actual decapitated head with gaping nostrils and sagging mouth, whose teeth are apparently taken from executed criminals condemned by the mask, which functioned as judge and lawgiver until the late 1930s, when forced into retirement by a bureaucrat. Apparently this mask was regarded as so dangerous that it was brought to meetings wrapped in a black cloth. Its bangles each represent particular victims for whose deaths it was responsible.

It is rare to find reliable reports connected with a specific piece. The History of Art in Africa illustrates a mask that resembles an actual decapitated head with gaping nostrils and sagging mouth, whose teeth are apparently taken from executed criminals condemned by the mask, which functioned as judge and lawgiver until the late 1930s, when forced into retirement by a bureaucrat. Apparently this mask was regarded as so dangerous that it was brought to meetings wrapped in a black cloth. Its bangles each represent particular victims for whose deaths it was responsible.

One of the group’s most intriguing features is the mixed character of the beings brought together and organised symmetrically. There’s a small elephant mounted on the large figure’s head, and two children or deputies whom he holds at arm’s length. It is a mysterious and powerful group which only runs into trouble when we attempt detailed interpretation. Is it a portrait of a particular family which would have been kept in their house, or a cosmological diagram commissioned by the tribe and taking part in its ceremonies, even briefly worn on someone’s shoulders as if it really were a mask? It’s the old problem of wanting to give an African object a history, and feeling that the more one insists, the more one is making it up.

One of the group’s most intriguing features is the mixed character of the beings brought together and organised symmetrically. There’s a small elephant mounted on the large figure’s head, and two children or deputies whom he holds at arm’s length. It is a mysterious and powerful group which only runs into trouble when we attempt detailed interpretation. Is it a portrait of a particular family which would have been kept in their house, or a cosmological diagram commissioned by the tribe and taking part in its ceremonies, even briefly worn on someone’s shoulders as if it really were a mask? It’s the old problem of wanting to give an African object a history, and feeling that the more one insists, the more one is making it up.

Deciphering the spirit in which the Wellcome’s objects were collected would be an absorbing study. A fantastic intent surfaces more than occasionally. Among my favourites were a poster showing the furthest nightmare of a user of the old kind of toothpaste tube that split or fractured easily, resulting in mock carnage that takes unspeakable humanoid form.

Deciphering the spirit in which the Wellcome’s objects were collected would be an absorbing study. A fantastic intent surfaces more than occasionally. Among my favourites were a poster showing the furthest nightmare of a user of the old kind of toothpaste tube that split or fractured easily, resulting in mock carnage that takes unspeakable humanoid form.

Like the Tate, the Wellcome tempts you to keep going when the exhibition is over, straying into other rooms wondering what you will find there, perhaps another instrument of torture, like the early X-ray machine that resembles a treadmill turned on its side

Like the Tate, the Wellcome tempts you to keep going when the exhibition is over, straying into other rooms wondering what you will find there, perhaps another instrument of torture, like the early X-ray machine that resembles a treadmill turned on its side