Sometimes I wonder if these works of Twombly’s are really there at all. Maybe I am in similar doubt about some of my favourite poems. One day I would like to give a kind of police report on Wallace Stevens’ ‘Notes Towards a Supreme Fiction’. At first, I could make almost nothing of it, then I thought it was the most marvellous thing, then I just didn’t get it all over again.

Twombly’s sculptures share something with this troublesome poem. At least Stevens’ poems all have titles. Twombly’s sculptures mostly don’t. All those missing titles are like unwritten poems, which have been allowed to escape unrecorded. And in some way, that is that, a condition there’s no cure for. Ones that do have titles have inspired some of the most wonderful interpretations ever. This artist’s so-called sculptures seem to attract philosophers as vinegar does fruit flies. You can’t see why they would, but there’s no denying that they do.

Giorgio Agamben, a formidable Italian thinker, who appeared in Pasolini’s Gospel film (as the disciple Philip) and whom I revere because he discovered two manuscripts of Walter Benjamin’s missing since 1940, produced one of the most beautiful and far-fetched pieces of interpretation that I know, inspired by a particularly messy Twombly which, in lieu of a title, has a few lines of Rilke attached, which are artlessly (ha!) scribbled on a little piece of cardboard at the base of a plaster mound that holds two sticks, one standing straight, the other leaning against it, the two crudely wired together after an earlier accident.

Rilke speaks of happiness sought by laborious ascent or happiness falling unexpectedly. Agamben makes the two sticks an acting-out of these two motions, and sees in the two of them a picture of the difference between poetry and prose, poetry which can (and even must) always turn back, and prose which carries on. He makes the two sticks carriers of momentous meanings, which you can never un-see after you’ve followed his thoroughly poetic exposition.

My other example is the sculpture called Untitled (Funerary box for a lime-green python) which consists of two palm leaves raised on slender sticks which spring from a narrow wooden box not really big enough to hold a large snake. Like Joyce giving Homeric titles to the chapters of Ulysses and then taking them away, Twombly unwished his whimsical title for this work that momentarily connected it with Egypt and animal gods. The Harvard philosopher Arthur Danto made the most serpentine game out of applying and taking away the name to and from the object.

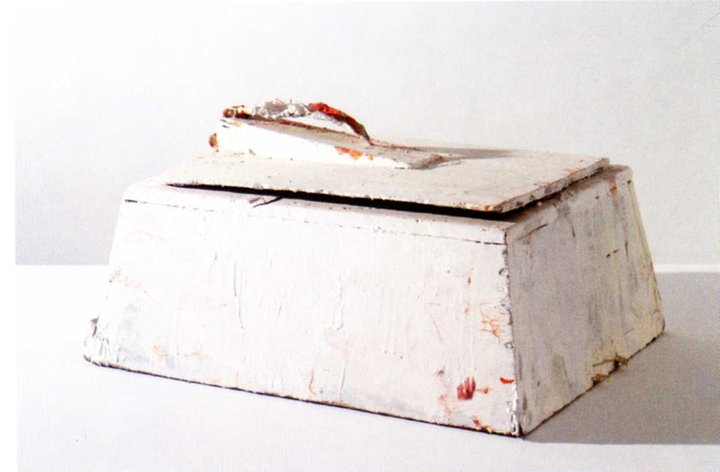

How could I have allowed the critics to usurp the space before the works themselves have spoken? In a real sense the untitled sculptures are the essential core of Twombly’s work as a sculptor who takes cast-off flotsam from the ordinary world and works magical transformations on them, turning them into something else entirely, without losing any fraction of their embarrassing crudity and imperfection. ‘White paint is my marble’ doesn’t mean as you might suppose that Twombly really sees himself as a rival of the Greeks. As often as not, he doesn’t even hide the underlying textures of his scrap of wood, now accorded a new importance without being allowed to leave its dismal past behind.

In a twist that surprises us, Twombly allows a few casts in bronze or resin of some of the most memorable sculptures. The best thing about this is that the bronzes often look more battered or ruined than the original.

In a twist that surprises us, Twombly allows a few casts in bronze or resin of some of the most memorable sculptures. The best thing about this is that the bronzes often look more battered or ruined than the original.

The contrast between the wooden pan-pipes and the bronze ones is a clear case of these confusions. The nails and bits of string sticking out in this sculpture, which are so hard to account for and so unmanageably alive, completely destroy the decorum that is such an important element of this most classical subject, and constitute another subversion of every unambiguous meaning. One of my favourite features of these endlessly baffling works is this final lack of resolution. You could, if you had the energy, go on puzzling at them for ever.

Why are the actors in the Batrachomycomachia (Battle between the frogs and mice)–an absurd parody of epic which possesses the patina of being taken as a work of Homer’s for so many centuries–why are these low creatures represented by a box of kindling, stacked in ramshackle fashion (like all the battlefields we have known), that rises from its container as if from the lake where it took place, now drenched in the colour of raspberry yoghurt?

Why are their nearest relative in Twombly’s work, the Vulci Chronicle, so abject, sparse like the records of that distant time, only a few vertebrae which stand for (and are, now) whole beings, who formerly stalked the earth spreading terror?

I could never have dreamed up Danto’s wonderful interpretation of another palm-leaf sculpture, but having come across it, I can not now un-think it. Cycnus (whose name means swan) was a hero, sufficiently obscure, who attracted the attention of a great hero (his name forgotten) who failed to reckon with Cycnus’ mother’s powers, who could extract him from his armour like the butterfly from its brittle shell and let him fly away, so the hero finds only the empty husk. Danto discovers perfect sense in the leaf as the bird and the block of wood as the earthbound prison of the armour.

In some sense it makes all the difference that Twombly himself became the man who wasn’t there, who left America so early for Rome, the old, universal seat of memory. All of the sculptures are as much about not being able to remember essential elements as about successful recovery. There is a whole series of Thickets which show one twig-like tree instead of a tangle, sometimes hung with forlorn tags listing the names of eight Sumerian cities, which survive now in very little but their names. These thickets are missing most of their elements but have nonetheless been linked with the ram in the thicket which saves Abraham from sacrificing Isaac. I don’t know who first connected this ram and this thicket with the ‘famous Billy Goat of Ur’ (as Panofsky calls him), a deity or a sacrifice (according to your taste) now in the British Museum. Scholars tell each other these are not the same animal or the same function, but Twombly piles up meanings rather than keeping them apart. His most austere version of the thicket theme looks like a scaffold and is only a thicket by virtue of two plastic flowers raised four feet in the air through a grotesque inflation, but the evocative title remains all-important. In some sense it’s all we’ve got.

One of the most moving recent realisations of a Theatre of Memory in Rome, William Kentridge’s Triumphs and Laments, creates a whole series of historical ikons by blowing up small ink drawings to monumental scale while keeping their calligraphic nonchalance, a magical preservation which wouldn’t last, for they were painted on the Tiber walls with washable pigments designed to fade.

![34 ptg twombly untitled [say goodbye catullus to the shores of asia minor]1994 room w huge mural menil houston.jpg](https://robertharbisonsblognet.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/34-ptg-twombly-untitled-say-goodbye-catullus-to-the-shores-of-asia-minor1994-room-w-huge-mural-menil-houston.jpg?w=739)

Twombly’s largest painting, fifty-two feet long, now displayed in a barn in Houston made specially to contain it, is called Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the shores of Asia Minor (several previous titles, like memories that fail, were combusted on the bonfire of this one). I have come to wonder if Twombly’s sculpture isn’t an extended meditation on remembering and forgetting. He is said to have spent the nights reading and the days in the studio. The work brims over with references to Rilke, Seferis, Archilochus and Cavafy but no Stevens, Hopkins, Eliot. Verses from more exotic languages are always transcribed in English. The biggest and most perplexing work in the exhibition at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, that got me looking at Twombly in the first place, was called A Time to Remain and a Time to Go Away, a bare-bones description of memory or of a relation to history.

The work consists of another steep ascent and precipitous fall. A slender frame contains an exuberantly molten platform-mound of plaster heaving with life, but the overall impression is something like a guillotine waiting to descend. The childish quality of Twombly’s inscribings makes me think of a-semic writing, writing that looks like words but isn’t, a mode with which Twombly filled whole canvases in certain phases of his career.

The work consists of another steep ascent and precipitous fall. A slender frame contains an exuberantly molten platform-mound of plaster heaving with life, but the overall impression is something like a guillotine waiting to descend. The childish quality of Twombly’s inscribings makes me think of a-semic writing, writing that looks like words but isn’t, a mode with which Twombly filled whole canvases in certain phases of his career.

Not in a literal sense, for he was immensely productive, he is the sculptor of figures missing, voyages cancelled, and settings abandoned by their inhabitants. Alongside the tombs, thickets, and scaffolds is a more mysterious subject to which I am drawn, the lump of plaster of geological character deposited on a cultural form like a brick or a box. What does it mean? Another memorial? Can it be thought, reason, art crushed dwarfed snuffed out by some mindless force? Why would any viewer particularly like contemplating that? It is history as the energy that takes things away and hides them from view.

‘White paint is my marble.’ At once dumb and magical. It is impossible to believe in this substitution, metamorphosis, overturning. Yet you want it to be true–the imagination lives in and for such fictions.