I didn’t intend to write about Vuillard again, but hadn’t anticipated how different the small (but much bigger) exhibition in Bath (appearing later in Edinburgh and Dublin) would be from the one last year in Birmingham. Birmingham was entirely caught up in the limited cast of characters of the household. Bath ranged outside and beyond the house, still keeping the view rigorously confined, Vuillard’s guiding feature being a voluntary confinement in which dislocations of vision can act with explosive force, freaks of perception which don’t necessarily lead to untethered or unfathomable emotions but into an emotional no-one’s land to which the right comparison might be Kafka.

The exhibition began in the home, with an awkward family scene in the weird green light of evening. Three generations are gathered round the table, along with two looming bottles like extra guests.

We recognise the mother, grandmother, and daughter from our last outing with Vuillard. We could mistake the lone orange-bearded male for the artist himself, but the label steers us toward his brother, an unknown quantity. The sister dominates, in a grotesquely twisted pose which reveals depths already familiar to the others, less so to us. She is wearing a dress like one in a portrait nearby, in a pattern like a lot of lively worms. Maybe she will explode.

Next to this dinner table is The Ear, one of the oddest little pictures Vuillard ever produced. It shows the head and shoulders of a young female bent over and concentrating on something on the floor. Is she tying her shoe or looking for something lost? We are already far ahead of ourselves, because she doesn’t really look like a person at all. Her ear we only recognise through the helping hand of the picture’s title: it looks more like a half-closed eye. Beneath it are two detached bits of brightly lit flesh which could be the tip of a nose and part of an upper lip. Otherwise, shadow, with traces of an eyebrow (doubtful) and cheek (obscured by strands of hair). Above the features, elements of a punk hairdo in black and orange stripes, plaited into a denser chequered pattern beyond. Over the invisible forehead dangles a big black spider of loose hair-strands.

Maybe this picture just goes to show how far Vuillard’s need to strangen the familiar features of the world could go. Here the supposed subject pretty well escapes, and solutions to the uncertainty leave plenty of uneasiness behind.

Very soon after comes another conundrum-picture that has an easier resolution. Two men in top hats seen close-up from behind. The sheen on one of the hats completely bisects the black mass, making it into two separate hats. But the deeper weirdness of this picture occurs further to the left. Instead of a hat, a giant black hand with four black fingers extended upward. This turns out to be another hat (or hair-do) after all, though one like a finger puppet mounted on a woman’s head, whose fainter body appears beneath. Like the others, this picture comes close to a visual joke. How can such a tiny sliver of reality constitute a subject? Well, it seems to. You go on enjoying the odd leftover spaces between the hats, and the contrast between the ‘brims’, if you can count the most nearly horizontal ‘finger’ a brim. The overlapping of the three bodies makes a nice consistency against the wild variations overhead.

Except in a formal sense, to call these male-female divisions an antagonism would be going too far. More interesting confrontations tend to take place indoors. Of all the fresh Vuillards in Bath, one called The Manicure perplexed me most.

The picture starts from another extreme lighting effect, with the source hidden between the two figures. It took me several tries to decipher the manicurist, whose face doesn’t really appear, though turned toward us. Part of the explanation is that we are not on-axis with the couple, as we perhaps think, but skewed to their right. That is how the light can miss her face completely, leaving a dark mask more like a spinning top than a human head.

So the pleasure in this configuration comes from its inhuman weirdness. And then there’s the dark lump to the left of the central pair. In the end I see this lump as a balding father and his little girl, with a bright red ribbon in her hair. In the meantime I have thought her a pet monkey, or the two of them an African carving, or a piece of furniture with a cloth over it.

What is this love of occlusion, of hiding the subject in shadow, turning people into hulks or lumps, and blocking off the space between them? Wherever it springs from, it works. It invests humdrum activity with portent, in a space loaded throughout with inscrutable depths.

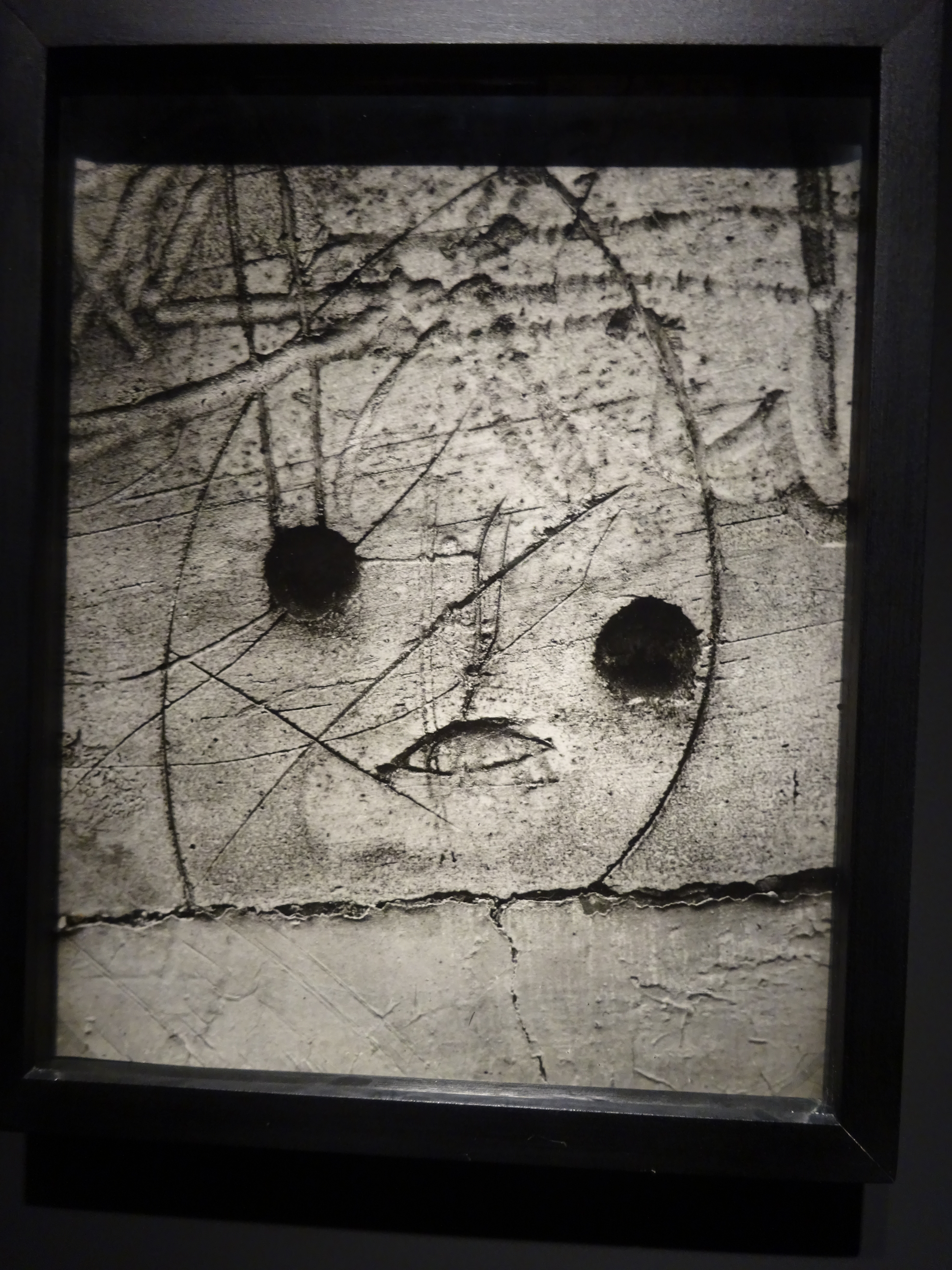

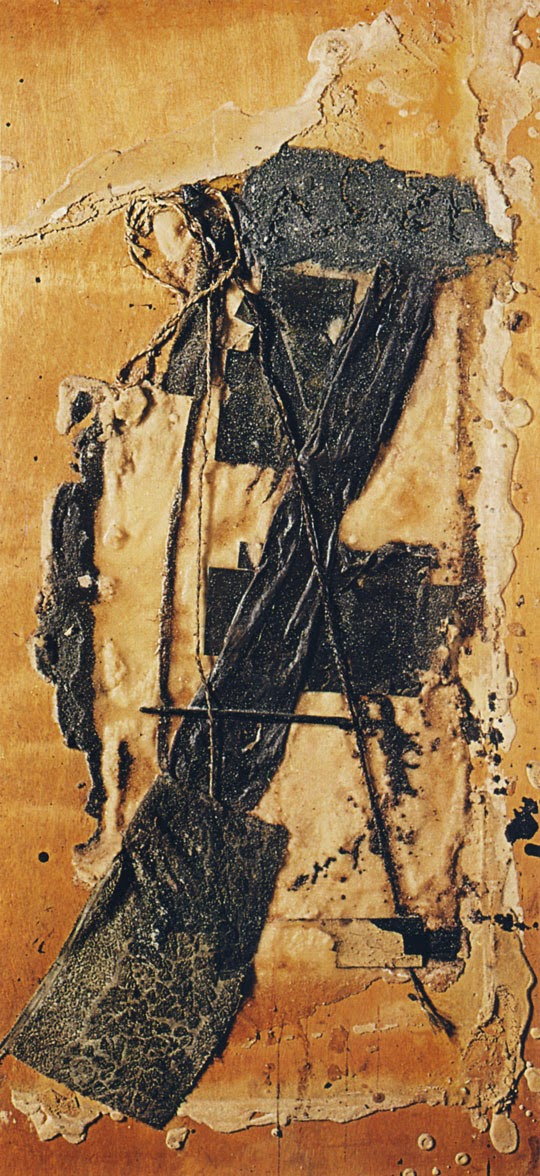

Other Vuillards thrive on blankness, not density, for a sense of a lot going on beneath a sparse surface. At first I took one of the most uncanny to be an expanse of sand leading to the forest-edge, with a track skirting it. At some point it dawned on me that this sand was not a beach but a wall blocking us off from the forest. And the traces of erased figures in the sand must have been marks on the wall, not occupants of the flatland. The two contrasting realms remain, one featureless, the other impenetrable. We think of other artists who value walls for their lack of content, like the Welshman Thomas Jones and the Catalan Antoni Tàpies.

In the exhibition the still life below gave an exaggerated impression of horizontality and of emptiness toward both ends, which doesn’t survive when it is isolated. I still think it is an exercise in dispersion and weightlessness, in spite of its magical vacancy having partly evaporated when it is removed from the peculiar space of the exhibition.

Publicity for the exhibition made a separate picture of the flowers in their vase, a little composition which soon fell to pieces, set against the ‘flowers’ of the tablecloth — bigger, vaguer, more unstable. All the elements are spread wide, and won’t sit down or cohere. The satchel is the worst, levitating rashly in mid-air, deserting its rightful place.

As in Birmingham, prints in Bath showed Vuillard dissolving reality’s there-ness even more radically than in paint. The cover of a set of lithographs has another strange confrontation between a hulking man (in pyjamas this time) and a younger woman. The girl by herself is a miracle of vagueness. In a couple of the prints in this series figures at tables merge magically into the setting and each other.

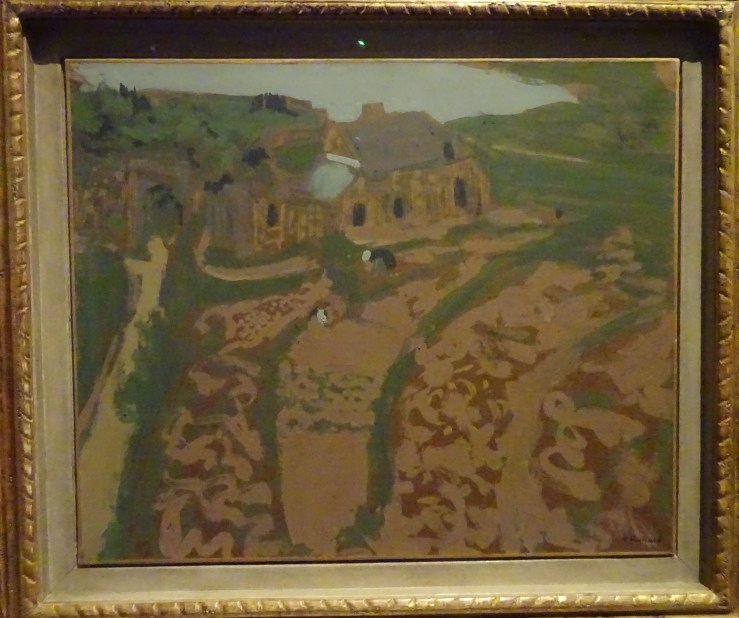

One of the best discoveries of the exhibition was the reappearance of glue-based distemper, a medium first met in Vuillard’s work for the theatre and now, in its reappearance, freeing him back into the boldness of the 1890s with two paintings of 1910 and after, one of a Breton farmhouse above a garden like an embroidery, whose rich pattern dissolves into squiggles, separate segments, and finally into chaos.

For Vuillard perception is always verging on disorientation. This flirtation with unreason is one of his deepest promptings, an escape down the rabbit hole of perception into a phantasmagoria of forms that have freed themselves from the restraints of sense.

Looking closely at the work in distemper, you find such dissolutions as a children’s smock like icing on pastry, and its mother’s dress a snow flurry, in a familiar world become entirely strange.