Lee Krasner spent a lot of time and energy interpreting and promoting the work of her husband. In a real sense Jackson Pollock was worth it, but it was thrilling to see in the recent exhibition at the Barbican that Krasner was producing at the same time a rich variety of work not in the least cowed by or under the spell of the Dionysian Pollock.

It is work of great intellectual depth and force, of ceaseless searching and renewal, so demanding and various that one visit wasn’t enough to take it all in.

The exhibition began with the so-called tiny paintings, small in themselves and full of further levels of tinyness, little knots of activity scattered over the canvas. Labels spelled out the theory of this organisation, that small things can become monumental depending on context and your own focus. So you grasped from the start that Krasner was a visionary who saw metamorphically, which set you up to expect transformations in which all is not what it seems.

Soon after, we came to her student work, charcoal nudes called life studies, that started looking like Michelangelo and moved on to Picasso-like fractures, a radically disruptive idea of taking dictation from nature. At this point did any of us dream that the end of it all would be the beginning?

After the impinging nearness of the nudes came unlikely wartime collages meant for window displays and populated by bombs, bombers, scientific instruments and scientists’ laboratories, full of fractious life. This was the period in which she met Pollock, as she oversaw a group of mainly male artists in a bold, practical project.

Soon after the war she is doing something even more imaginative with collage, slicing up compositions she is dissatisfied with and forming them into powerful explosions which still carry narrative force, bursts of light, tangles of undergrowth, tumult in the heavens. Unlike most of her contemporaries, she went on giving descriptive or allusive titles to her pictures, which told viewers to look for rich imagery in seeming abstraction. Not just ‘seeming’ perhaps, for Krasner shows that these canvases can be both pure construction and individualised narrative at once.

One of the best surprises was to move from one side to the other of the square donut of the upper storey at the Barbican, from the small, dense collages of 1954 to large, free Pollock-sized ones of the very next year.

Both sets, the small and the large, are among her best works, and those viewers who thought they saw suspiciously Pollock-like scribbles in one of the larger set called Bald Eagle were right. Here Krasner cannibalised her own rejected canvases and one of Pollock’s too, which plays the part of the bird.

In these pictures it’s more evident that new work is made from the ruins of the old, that new energy springs from the destruction of what went before, through ripping, shredding or cutting without much respect for earlier effort.

So certain colours have special meanings, and red is a kind of bloodshed in Bird Talk for instance (opening image). In this room Milkweed provided a measure of this—its cool colours seemed out of place.

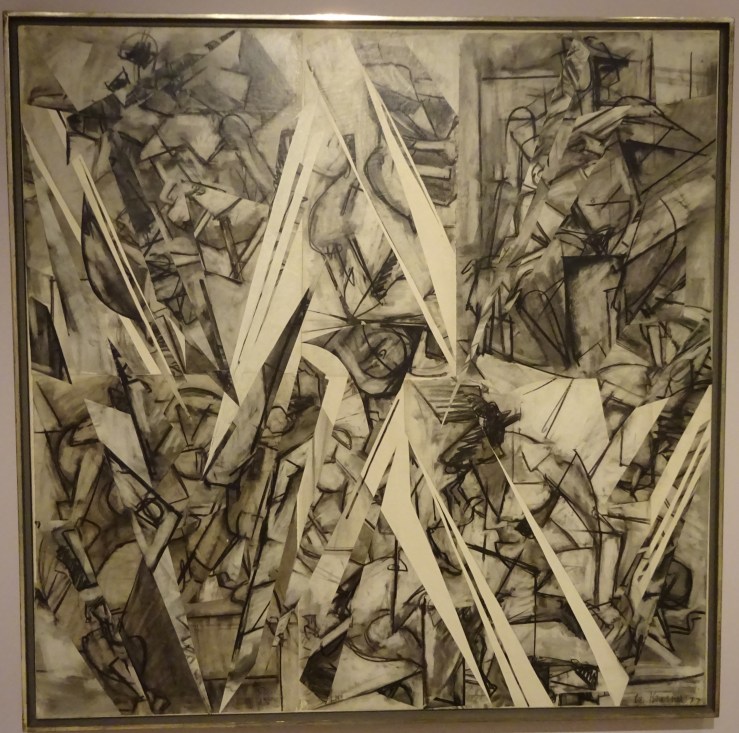

Krasner’s best years in paint were difficult years with Pollock. One of the most exciting and disturbing rooms contained four violent paintings on bodily themes from just before and just after Pollock’s death, which occurred when Krasner had escaped briefly to Paris. You could fill a much larger room with the anguished work of that year and the next, among the most wonderful things Krasner ever did.

This is where my attention finally wore out, after these pictures in flesh tones and grey, which might be evenly divided between anger and grief, but there’s nothing balanced about them. They are barely controlled, which makes them so uncomfortably exciting. They keep calling themselves back to order, and the canvas gets more and more crowded with colliding forms. They are sometimes said to derive from Picasso’s Demoiselles, to which they seem worthy rivals.

Perhaps Krasner had already been shifting to soberer palettes in works like Cauldron (not in exhibition), but when we moved to the lower floor at the Barbican we were in a surprising new monochrome-world which might at first seem a diminishment, but resulted in a pair of masterpieces on a grand scale, a calm cloudscape or vast Northern expanse called Polar Stampede, and the wildest depiction of movement, The Eye is the First Circle, which incorporates whirlwind vortexes and heroic striding figures, a range of diffuse and focused motion which accompanies you as you walk past it. Did Krasner have in mind Pollock’s largest canvas, the regular/irregular Mural, meant for Peggy Guggenheim’s New York flat, Krasner’s seething crowd played against Pollock’s orderly procession?

The almost-grisaille effect of Krasner’s umber paintings lets the formal power of the composition come out more clearly, but there’s also a more prosaic explanation of the source of this unexpected swerve in her work. The larger canvases are possible because she has moved into Pollock’s much bigger studio at their Long Island house. And the absence of colour has its source in her insomnia—she takes to painting at night by artificial light, doesn’t like what happens to colour in these conditions and hits on brown as a tone unspoiled by them.

There are more new departures in the 1960s and 70s, ‘flower’ paintings like Through Blue of 1963, made with a broken right arm which left her manipulating paint with her fingers, leading to great density of surface, and a spate of cartoon-like canvases including Courtship and Mister Blue of 1966.

The exhibition ended with a startling return. Rooting around in the studio, a British friend found a large cache of charcoal nudes from student days. Krasner meant to destroy them, but looking more closely, felt she was being directed to turn them into something new. Instead of tearing, this time she cut them up with scissors. Out of this destruction came remarkable and unnerving works, in part her revenge on a teacher she had both revered and resented. He had once torn up one of her drawings.

The results of the butchering are tantalysing and confusing, like a Baroque ceiling with figures tumbling out of the corners, like Michelangelo’s lounging or sprawling figures anchoring an indistinct turmoil of other figures, like a series of movements only beginning to clarify themselves, and suggesting as so often in Krasner’s canvases that much bodily business remains to unfold.

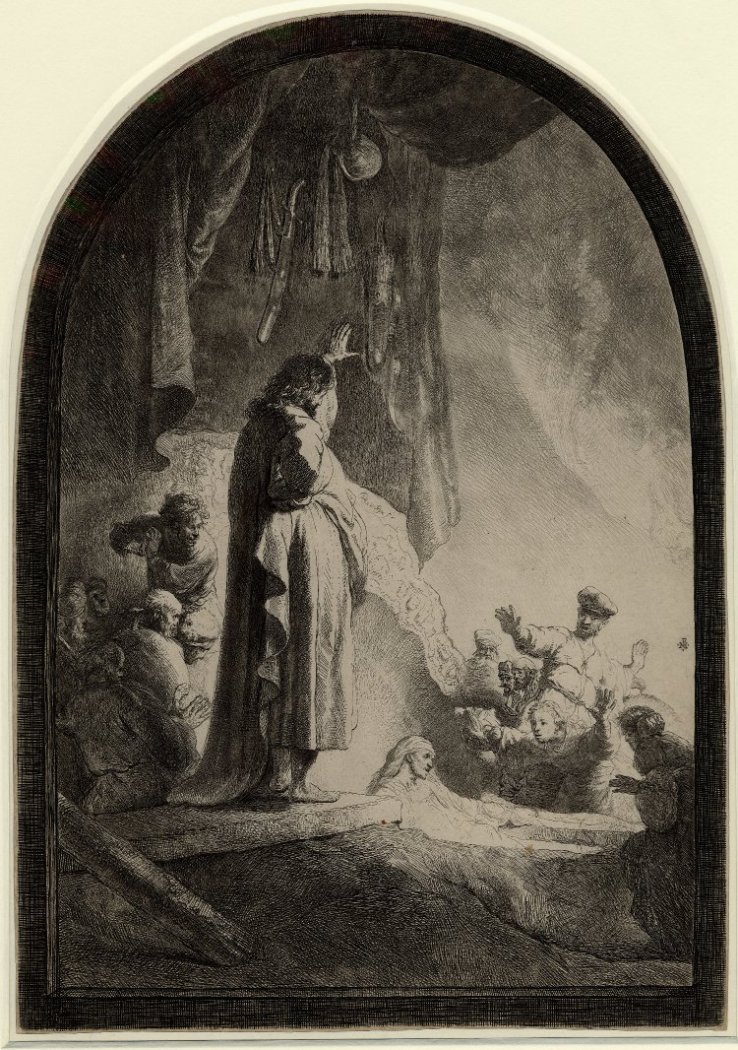

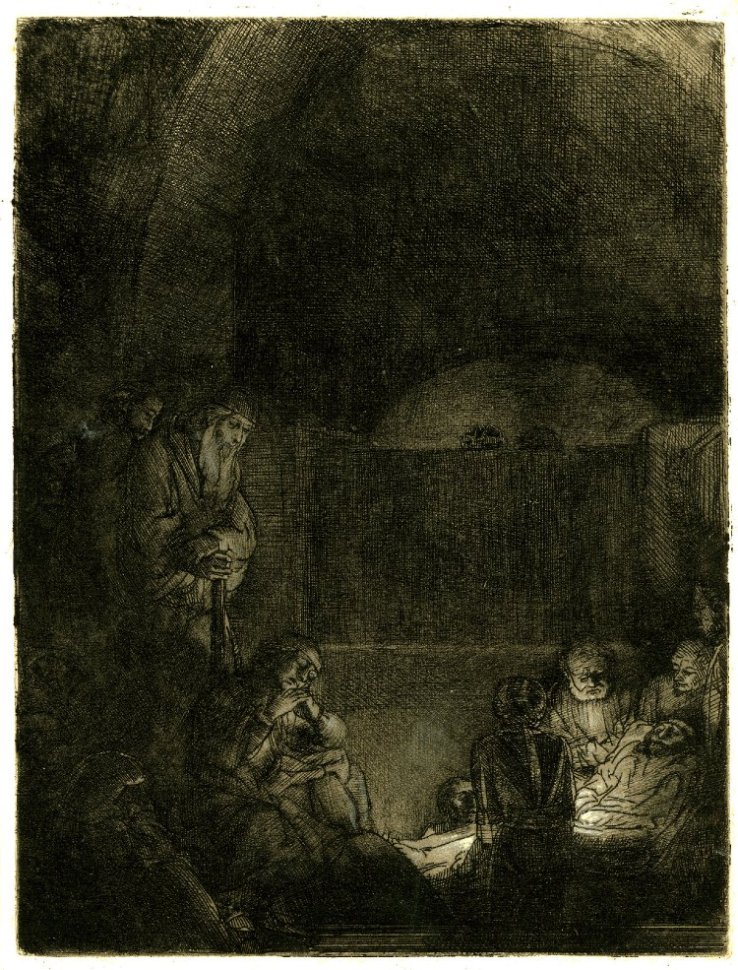

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically.

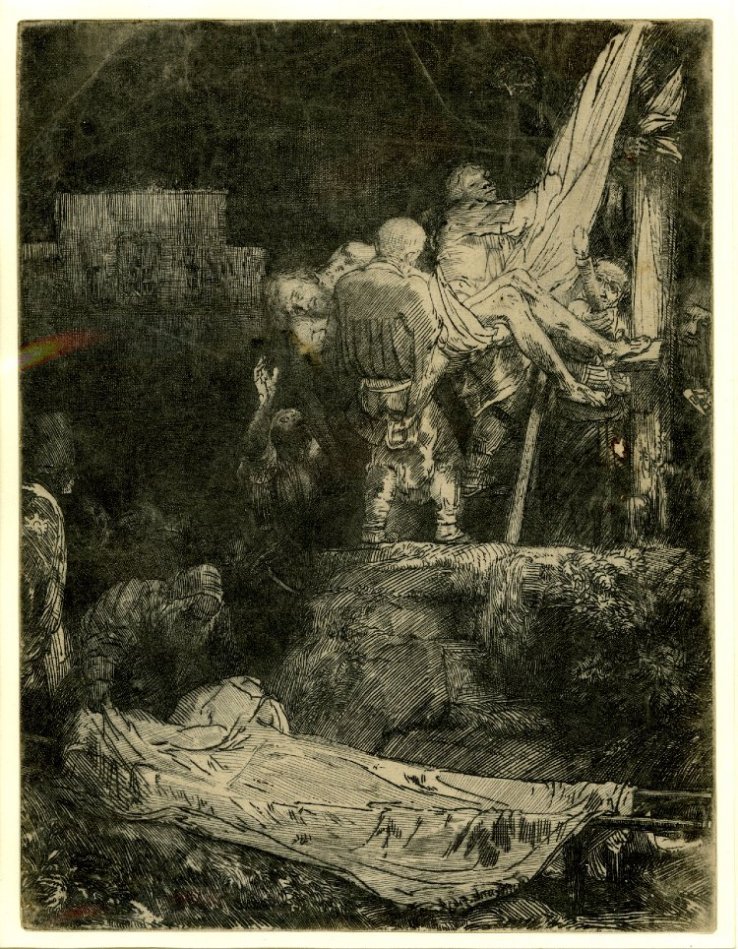

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically. Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Then

Then

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of. In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving.

In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving. There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within.

There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within. In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

Its subjects exist outside history in a world ruled by metaphor, like a huge butterfly mask in Washington with four birds and three chameleons perched on it, stretching sideways for almost six feet in a shape unlike any face that ever was. Labels for such objects too often simply show the limits of knowledge—dates are the date it was collected, or a guess–‘late 19th/ early 20th century (?)’—how often have we met that? Then comes an interesting debate about which of two nearby groups is more likely as the source of the work. In the meantime more intriguing questions have slipped away—why a butterfly? why such an abstract, bird-like form of butterfly? why such strident tattooing over the whole wing-surface of the flimsy creature? and the inversions of size, small birds & large butterfly—is that just a picture of thought roaming free, or a more specific puzzle to be solved? No answers, only questions.

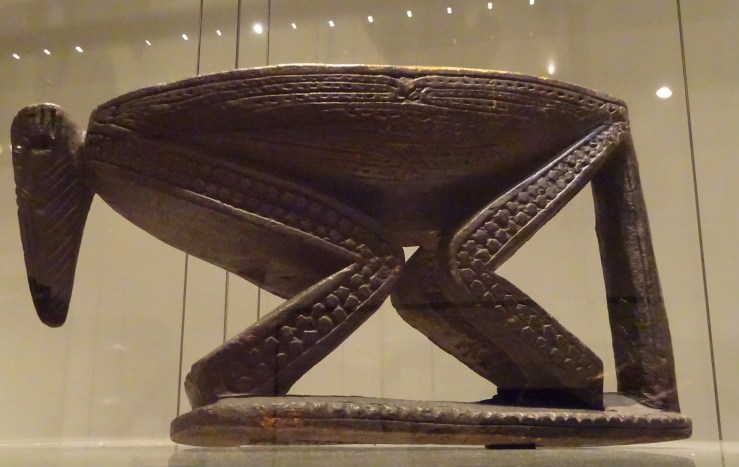

Its subjects exist outside history in a world ruled by metaphor, like a huge butterfly mask in Washington with four birds and three chameleons perched on it, stretching sideways for almost six feet in a shape unlike any face that ever was. Labels for such objects too often simply show the limits of knowledge—dates are the date it was collected, or a guess–‘late 19th/ early 20th century (?)’—how often have we met that? Then comes an interesting debate about which of two nearby groups is more likely as the source of the work. In the meantime more intriguing questions have slipped away—why a butterfly? why such an abstract, bird-like form of butterfly? why such strident tattooing over the whole wing-surface of the flimsy creature? and the inversions of size, small birds & large butterfly—is that just a picture of thought roaming free, or a more specific puzzle to be solved? No answers, only questions. Ordinary objects are turning into animals, like a stool ingeniously composed of a long nosed beast which can fold its limbs into a stool with none left over or sticking out, an improbable completeness in disparate realities aligned. Less immediately perplexing are appliances embellished with a single or a couple of animal features, a big container with a head and a tail, or a backrest with a ram’s head at the top and two supports turning into his front legs, the rest of him nowhere to be seen or thought of as continuing underground.

Ordinary objects are turning into animals, like a stool ingeniously composed of a long nosed beast which can fold its limbs into a stool with none left over or sticking out, an improbable completeness in disparate realities aligned. Less immediately perplexing are appliances embellished with a single or a couple of animal features, a big container with a head and a tail, or a backrest with a ram’s head at the top and two supports turning into his front legs, the rest of him nowhere to be seen or thought of as continuing underground. It is wrong to view the animal features as embellishments or decoration of a useful object. They are all we need to turn a thing into a being. Even a modern Westerner, susceptible enough to the literal mindedness that runs deep in all art, will seize on the slightest signs that the inanimate is becoming animate to take the hint, carry it further and complete the conversion, even in the case where what I took for a large storage container made from a log is actually a slit-drum for sending long-distance messages by banging on its sides with wooden hammers. I reckoned it a giant ant-eater, so stretched-out was its body, nine feet long, but everyone agrees that the head is another ram’s head, and the tail a ram’s tail, so these proportions call for difficult digesting by the viewer. Or perhaps its mass is so powerful that it overcomes all objections by that fact alone.

It is wrong to view the animal features as embellishments or decoration of a useful object. They are all we need to turn a thing into a being. Even a modern Westerner, susceptible enough to the literal mindedness that runs deep in all art, will seize on the slightest signs that the inanimate is becoming animate to take the hint, carry it further and complete the conversion, even in the case where what I took for a large storage container made from a log is actually a slit-drum for sending long-distance messages by banging on its sides with wooden hammers. I reckoned it a giant ant-eater, so stretched-out was its body, nine feet long, but everyone agrees that the head is another ram’s head, and the tail a ram’s tail, so these proportions call for difficult digesting by the viewer. Or perhaps its mass is so powerful that it overcomes all objections by that fact alone.

It isn’t really in the same class-–creating fear or disturbance—but the famous mask with twelve eyes might be in its way just as intimidating. The rules of ordinary reality give way all at once without a chance to discuss them. Of all the objects in this series, this is the one which most needs to be seen in isolation for full effect, surrounded by a void, a true minimalist reduction.

It isn’t really in the same class-–creating fear or disturbance—but the famous mask with twelve eyes might be in its way just as intimidating. The rules of ordinary reality give way all at once without a chance to discuss them. Of all the objects in this series, this is the one which most needs to be seen in isolation for full effect, surrounded by a void, a true minimalist reduction.

It is rare to find reliable reports connected with a specific piece. The History of Art in Africa illustrates a mask that resembles an actual decapitated head with gaping nostrils and sagging mouth, whose teeth are apparently taken from executed criminals condemned by the mask, which functioned as judge and lawgiver until the late 1930s, when forced into retirement by a bureaucrat. Apparently this mask was regarded as so dangerous that it was brought to meetings wrapped in a black cloth. Its bangles each represent particular victims for whose deaths it was responsible.

It is rare to find reliable reports connected with a specific piece. The History of Art in Africa illustrates a mask that resembles an actual decapitated head with gaping nostrils and sagging mouth, whose teeth are apparently taken from executed criminals condemned by the mask, which functioned as judge and lawgiver until the late 1930s, when forced into retirement by a bureaucrat. Apparently this mask was regarded as so dangerous that it was brought to meetings wrapped in a black cloth. Its bangles each represent particular victims for whose deaths it was responsible.

One of the group’s most intriguing features is the mixed character of the beings brought together and organised symmetrically. There’s a small elephant mounted on the large figure’s head, and two children or deputies whom he holds at arm’s length. It is a mysterious and powerful group which only runs into trouble when we attempt detailed interpretation. Is it a portrait of a particular family which would have been kept in their house, or a cosmological diagram commissioned by the tribe and taking part in its ceremonies, even briefly worn on someone’s shoulders as if it really were a mask? It’s the old problem of wanting to give an African object a history, and feeling that the more one insists, the more one is making it up.

One of the group’s most intriguing features is the mixed character of the beings brought together and organised symmetrically. There’s a small elephant mounted on the large figure’s head, and two children or deputies whom he holds at arm’s length. It is a mysterious and powerful group which only runs into trouble when we attempt detailed interpretation. Is it a portrait of a particular family which would have been kept in their house, or a cosmological diagram commissioned by the tribe and taking part in its ceremonies, even briefly worn on someone’s shoulders as if it really were a mask? It’s the old problem of wanting to give an African object a history, and feeling that the more one insists, the more one is making it up.

Most harrowing of all the variations on these themes are a series of dangling victims strung up in the throes of death or its bedraggled aftermath. One of the chickens uncannily resembles a familiar form of ample female nude met in Hellenistic sculpture. This one also appears to crane eagerly upward via a grotesquely elongated neck, at odds with the tranquillity of the torso beneath.

Most harrowing of all the variations on these themes are a series of dangling victims strung up in the throes of death or its bedraggled aftermath. One of the chickens uncannily resembles a familiar form of ample female nude met in Hellenistic sculpture. This one also appears to crane eagerly upward via a grotesquely elongated neck, at odds with the tranquillity of the torso beneath.

![b7 24a 100 [x3] soutine dindon strung up copy 3.jpg](https://robertharbisonsblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/b7-24a-100-x3-soutine-dindon-strung-up-copy-3.jpg?w=739)