Lee Krasner spent a lot of time and energy interpreting and promoting the work of her husband. In a real sense Jackson Pollock was worth it, but it was thrilling to see in the recent exhibition at the Barbican that Krasner was producing at the same time a rich variety of work not in the least cowed by or under the spell of the Dionysian Pollock.

It is work of great intellectual depth and force, of ceaseless searching and renewal, so demanding and various that one visit wasn’t enough to take it all in.

The exhibition began with the so-called tiny paintings, small in themselves and full of further levels of tinyness, little knots of activity scattered over the canvas. Labels spelled out the theory of this organisation, that small things can become monumental depending on context and your own focus. So you grasped from the start that Krasner was a visionary who saw metamorphically, which set you up to expect transformations in which all is not what it seems.

Soon after, we came to her student work, charcoal nudes called life studies, that started looking like Michelangelo and moved on to Picasso-like fractures, a radically disruptive idea of taking dictation from nature. At this point did any of us dream that the end of it all would be the beginning?

After the impinging nearness of the nudes came unlikely wartime collages meant for window displays and populated by bombs, bombers, scientific instruments and scientists’ laboratories, full of fractious life. This was the period in which she met Pollock, as she oversaw a group of mainly male artists in a bold, practical project.

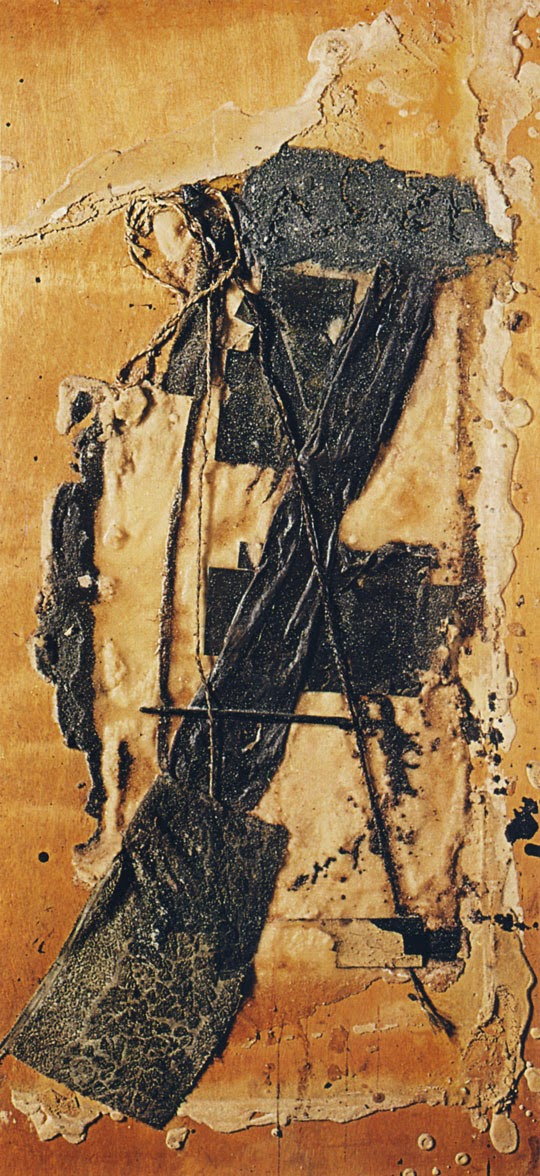

Soon after the war she is doing something even more imaginative with collage, slicing up compositions she is dissatisfied with and forming them into powerful explosions which still carry narrative force, bursts of light, tangles of undergrowth, tumult in the heavens. Unlike most of her contemporaries, she went on giving descriptive or allusive titles to her pictures, which told viewers to look for rich imagery in seeming abstraction. Not just ‘seeming’ perhaps, for Krasner shows that these canvases can be both pure construction and individualised narrative at once.

One of the best surprises was to move from one side to the other of the square donut of the upper storey at the Barbican, from the small, dense collages of 1954 to large, free Pollock-sized ones of the very next year.

Both sets, the small and the large, are among her best works, and those viewers who thought they saw suspiciously Pollock-like scribbles in one of the larger set called Bald Eagle were right. Here Krasner cannibalised her own rejected canvases and one of Pollock’s too, which plays the part of the bird.

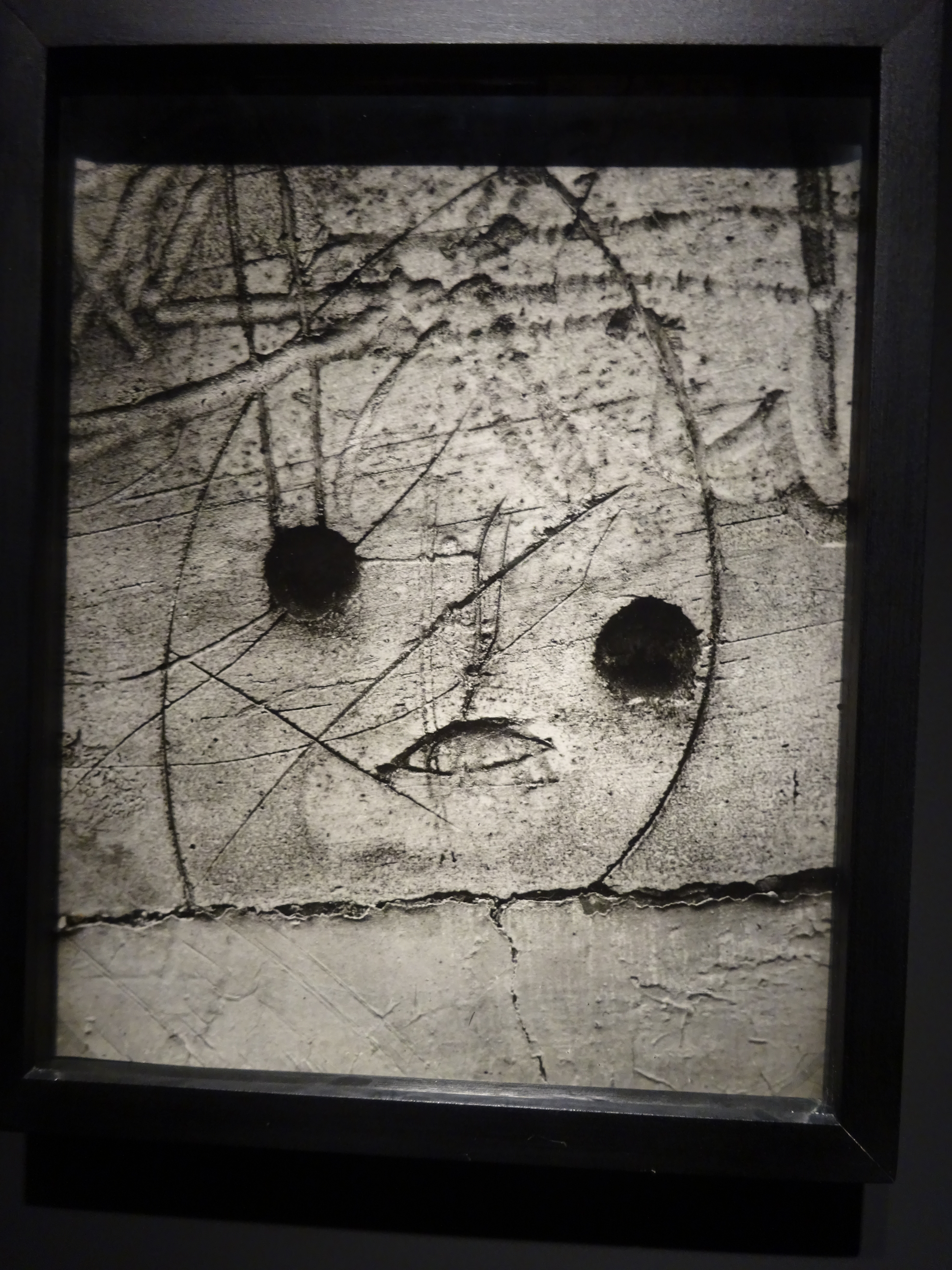

In these pictures it’s more evident that new work is made from the ruins of the old, that new energy springs from the destruction of what went before, through ripping, shredding or cutting without much respect for earlier effort.

So certain colours have special meanings, and red is a kind of bloodshed in Bird Talk for instance (opening image). In this room Milkweed provided a measure of this—its cool colours seemed out of place.

Krasner’s best years in paint were difficult years with Pollock. One of the most exciting and disturbing rooms contained four violent paintings on bodily themes from just before and just after Pollock’s death, which occurred when Krasner had escaped briefly to Paris. You could fill a much larger room with the anguished work of that year and the next, among the most wonderful things Krasner ever did.

This is where my attention finally wore out, after these pictures in flesh tones and grey, which might be evenly divided between anger and grief, but there’s nothing balanced about them. They are barely controlled, which makes them so uncomfortably exciting. They keep calling themselves back to order, and the canvas gets more and more crowded with colliding forms. They are sometimes said to derive from Picasso’s Demoiselles, to which they seem worthy rivals.

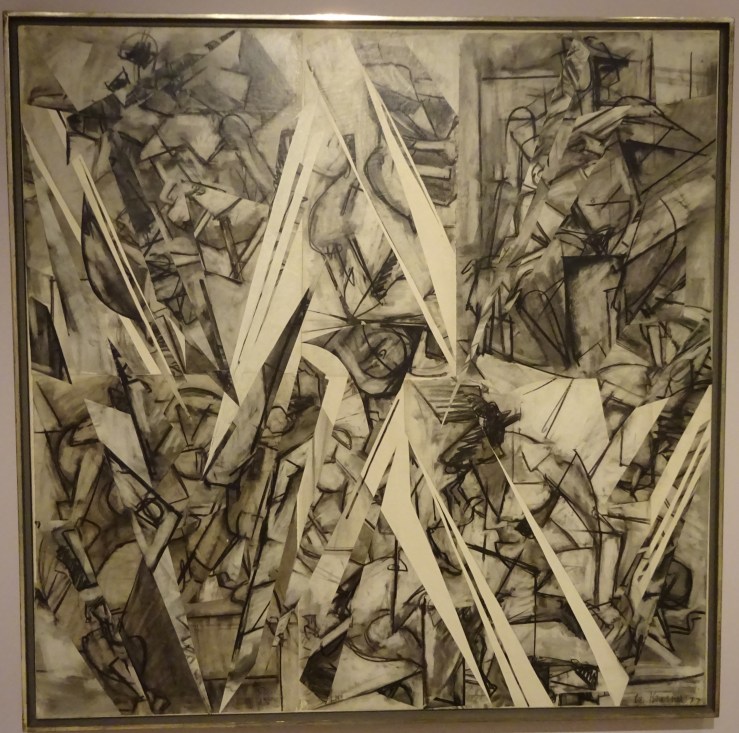

Perhaps Krasner had already been shifting to soberer palettes in works like Cauldron (not in exhibition), but when we moved to the lower floor at the Barbican we were in a surprising new monochrome-world which might at first seem a diminishment, but resulted in a pair of masterpieces on a grand scale, a calm cloudscape or vast Northern expanse called Polar Stampede, and the wildest depiction of movement, The Eye is the First Circle, which incorporates whirlwind vortexes and heroic striding figures, a range of diffuse and focused motion which accompanies you as you walk past it. Did Krasner have in mind Pollock’s largest canvas, the regular/irregular Mural, meant for Peggy Guggenheim’s New York flat, Krasner’s seething crowd played against Pollock’s orderly procession?

The almost-grisaille effect of Krasner’s umber paintings lets the formal power of the composition come out more clearly, but there’s also a more prosaic explanation of the source of this unexpected swerve in her work. The larger canvases are possible because she has moved into Pollock’s much bigger studio at their Long Island house. And the absence of colour has its source in her insomnia—she takes to painting at night by artificial light, doesn’t like what happens to colour in these conditions and hits on brown as a tone unspoiled by them.

There are more new departures in the 1960s and 70s, ‘flower’ paintings like Through Blue of 1963, made with a broken right arm which left her manipulating paint with her fingers, leading to great density of surface, and a spate of cartoon-like canvases including Courtship and Mister Blue of 1966.

The exhibition ended with a startling return. Rooting around in the studio, a British friend found a large cache of charcoal nudes from student days. Krasner meant to destroy them, but looking more closely, felt she was being directed to turn them into something new. Instead of tearing, this time she cut them up with scissors. Out of this destruction came remarkable and unnerving works, in part her revenge on a teacher she had both revered and resented. He had once torn up one of her drawings.

The results of the butchering are tantalysing and confusing, like a Baroque ceiling with figures tumbling out of the corners, like Michelangelo’s lounging or sprawling figures anchoring an indistinct turmoil of other figures, like a series of movements only beginning to clarify themselves, and suggesting as so often in Krasner’s canvases that much bodily business remains to unfold.