Writing is so familiar that it takes a real effort of imagination to remember that it needed to be discovered or invented. The Writing exhibition at the British Library put us back in the time when writing lay in wait for us, before we had stumbled upon it. The early stages remain obscure, images on cave-walls that we find expressive, a handprint surrounded by dots, at Pech Merle in France, for which the book of the exhibition supplies a literal translation, ‘I was here, with my animals.’

That might be regarded as proto-writing. What does the earliest true writing look like, then? Little pictures scratched on the shoulder-blade of an ox and standing for what the cracks and fissures in the burnt bone are trying to say?—this is a widely shared idea of the beginnings of writing in China, written characters springing out of the same natural forces that reveal themselves in animal remains. So writing keeps a flavour of the divine and never loses, however abstract it becomes, its strong link with the visible world.

In Mesopotamia writing appears more mundanely in fixing boundaries and accounting for possessions. There’s a persistent effort (a wish?) to trace these beginnings to Egypt. In 1905 this little sphinx was found, on which a British archaeologist thought he saw the first inklings of an alphabetic order, an ox-head facing left who was an early striving toward the letter A. His theory was refuted, only to rise again, with new evidence, in the 1990s.

The contest between syllabic and alphabetic systems reappears periodically in the exhibition, one of the most striking outcomes being the Chinese typewriter of the mid 20c, which instead of 40 keys has 4000+ characters lying on a flat bed, which must be picked up individually, pushed against the paper and then put back. Twenty characters a minute is the maximum speed achievable in this language, which can’t easily be atomised.

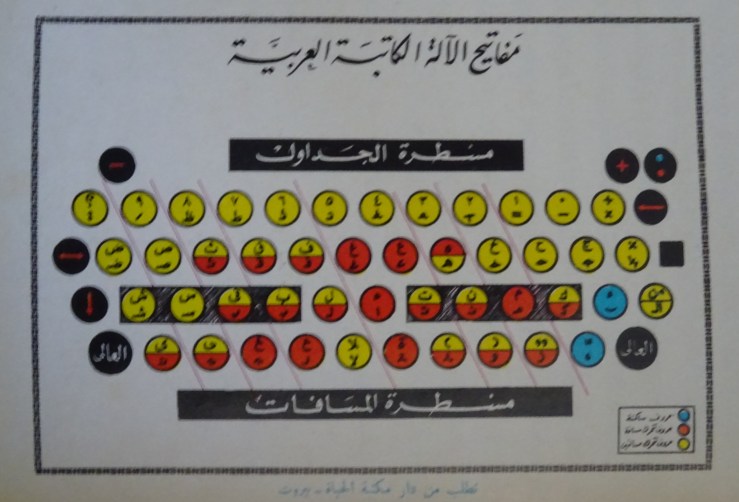

Apparently, switching alphabets is easy. Stick-on Hebrew, Thai and Tamil keyboards appeared in the exhibition. Above is an Arabic keyboard, which I cannot evaluate for completeness or attractiveness. It seems to double-up along different axes from the cap/ lower case mode of Roman keyboards.

The evolution of the letter A was traced through five stages, and we cheered them on as they got closer to the truth. We also delighted to learn that the last known inscription in cuneiform occurred in 75 AD and the last hieroglyphic text in 394.

The Vai language of Liberia and other parts of West Africa waited until the 1830s to find a written form, which was revealed to its discoverer Momolu Dwalu Bukele in a dream. This is syllabic not alphabetic; the text below tells part of a family history.

It is easier to believe that writing is intrinsically magical when everything about it is as foreign as it is here, but even Latin in cursive form, explained by the need to produce texts quickly, becomes mysterious again, all the more because it is clearly not fine writing striving for an artistic effect. This comes from the record of a sale of property in Rimini in 572.

Latin turns up again in coded form recording conventional material in 9th century shorthand, which again achieves prosaic savings of time and space. A slave of Cicero’s is credited with the invention of this system of abbreviations originally devised for preserving his master’s speeches. One wonders if the strange variety in the length of the strokes isn’t a form of play or mystification, throwing decoders off the track.

One of the most tantalysing exhibits was a Burmese album of tattoo designs in an intricate folding form. The images, all in white on black, were often obscured or interfered with by inscriptions in gridded lozenges, one letter or character per compartment, which made the text eat up large areas of the image. A horse-like animal’s head and chest were completely consumed by twenty-four characters in an 8 x 3 grid. Presumably the words that seem defacements to us were charms for which the whole project existed, and which only took effect when they were written on the body of the tattooee by a miracle-worker, equivalent to or more special than a priest.

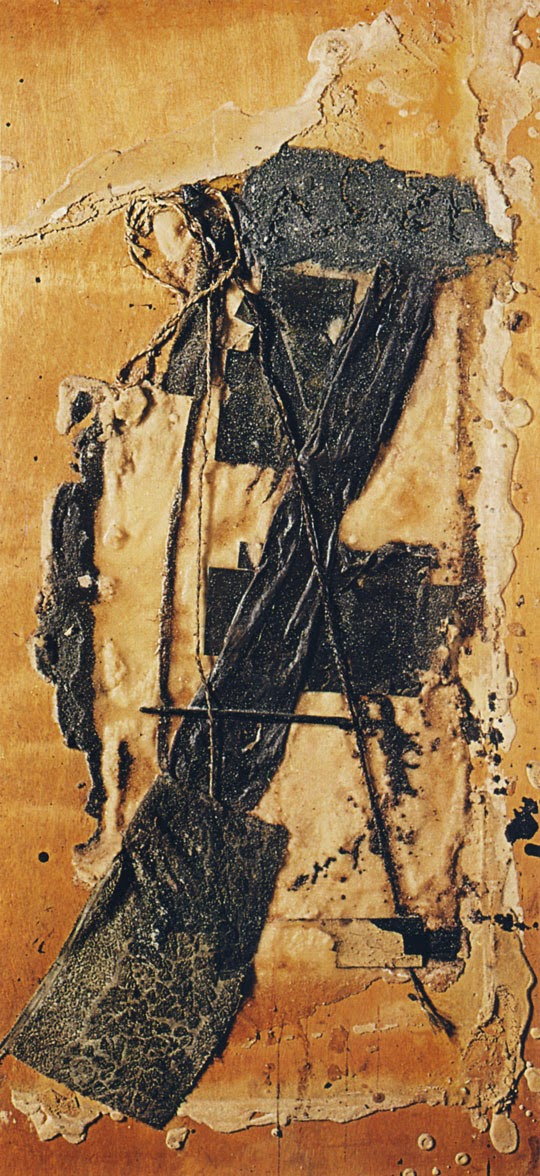

It is apparently a respectable theory and not just a Wordsworthian fantasy that the idea of the alphabet first appeared in the mind of a child. It is now a commonplace that the very young are most adept with the new forms of communication, which carry their oft-mooted threat to old forms of writing (by hand, for instance) or of dissemination (by printed books, above all). These changes inspired the present exhibition, which reminds us of a long and precious history but isn’t blind to such thrilling new forms of expression as eL Seed’s (a version of a medieval hero’s name, el Cid) calligraphy on an urban scale, an inscription urging us to cleanse our sight that stretches over fifty buildings in a despised district of Cairo populated by garbage collectors. The casual scribbles of teenage graffitists lie somewhere behind this enormous work, finally brought to pass in 2016, writing which transfigures the ruinous fabric of the city.

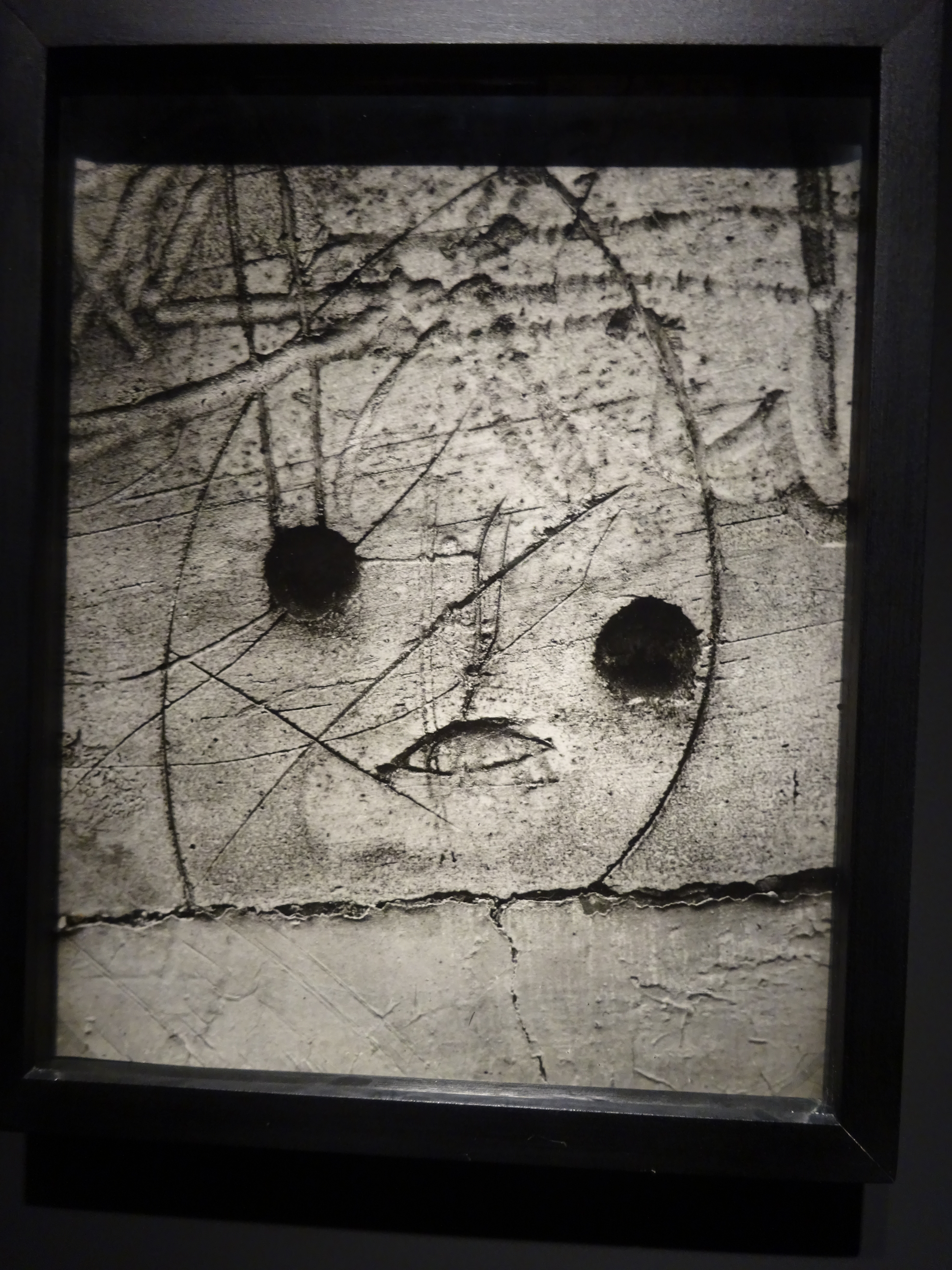

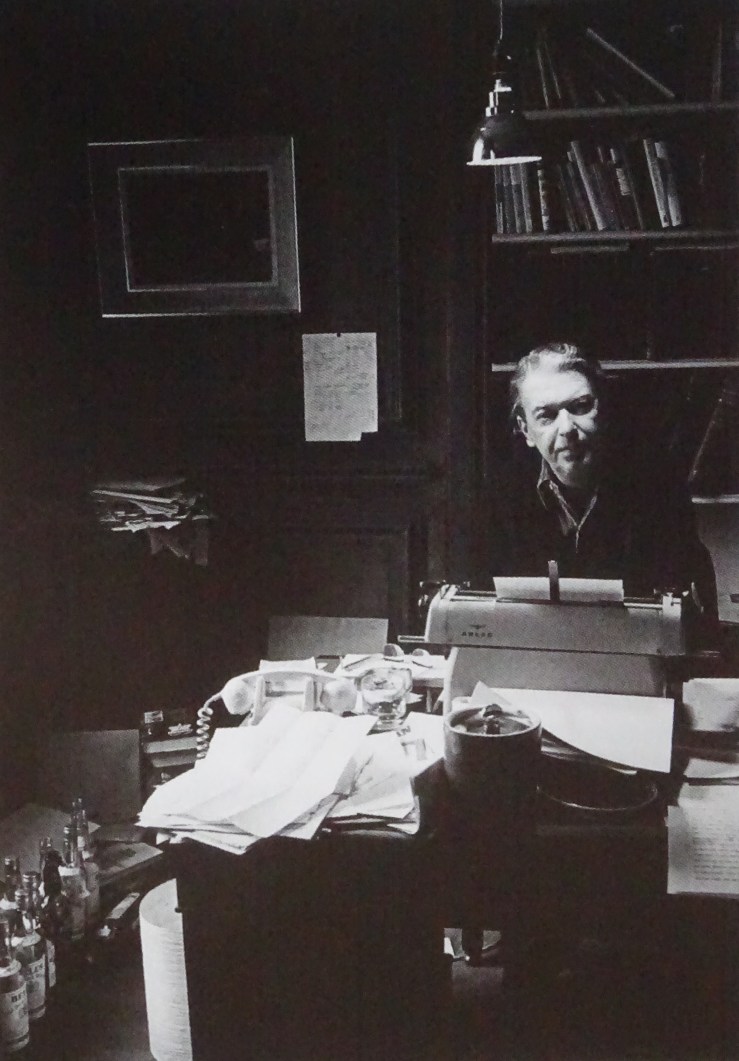

Another teenage ‘writer’ (the technical term in New York for a graffiti artist) was among the group of Syrian boy-graffitists whose arrest and torture for covering walls with slogans sparked off the Syrian revolution. Against this new outdoor form of writing we can put the old indoor, solitary form represented by an old white novelist, another breaker of moulds in his time.

Writing: making your mark at the British Library until 27 August 2019