Paula Rego is another outlier in the territory of contemporary art. She is Portuguese but came to London to study and now lives there. In some way she is more like a nineteenth-century novelist than a twenty-first century painter. She seems drawn to other painters for their subject matter rather than their handling of paint. Hogarth, Goya and James Ensor turn up in her comments about her own work, which often takes a literary work as the starting point, The Sin of Father Amaro (a scandalous Portuguese novel of 1875), Jane Eyre, Portuguese folk tales, English nursery rhymes, or a dark play by the British-Irish writer Martin McDonagh.

Paula Rego is another outlier in the territory of contemporary art. She is Portuguese but came to London to study and now lives there. In some way she is more like a nineteenth-century novelist than a twenty-first century painter. She seems drawn to other painters for their subject matter rather than their handling of paint. Hogarth, Goya and James Ensor turn up in her comments about her own work, which often takes a literary work as the starting point, The Sin of Father Amaro (a scandalous Portuguese novel of 1875), Jane Eyre, Portuguese folk tales, English nursery rhymes, or a dark play by the British-Irish writer Martin McDonagh.

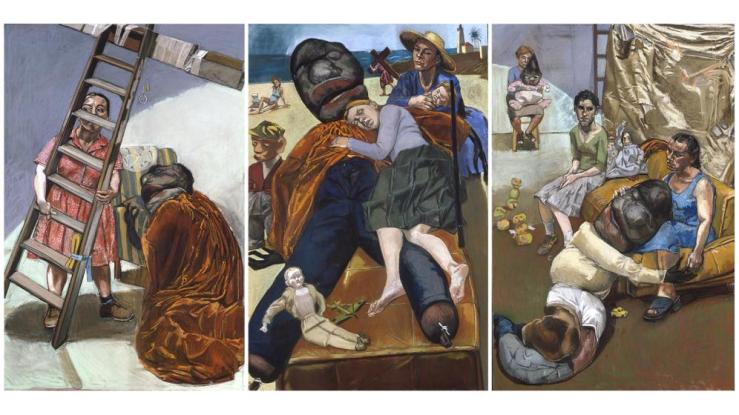

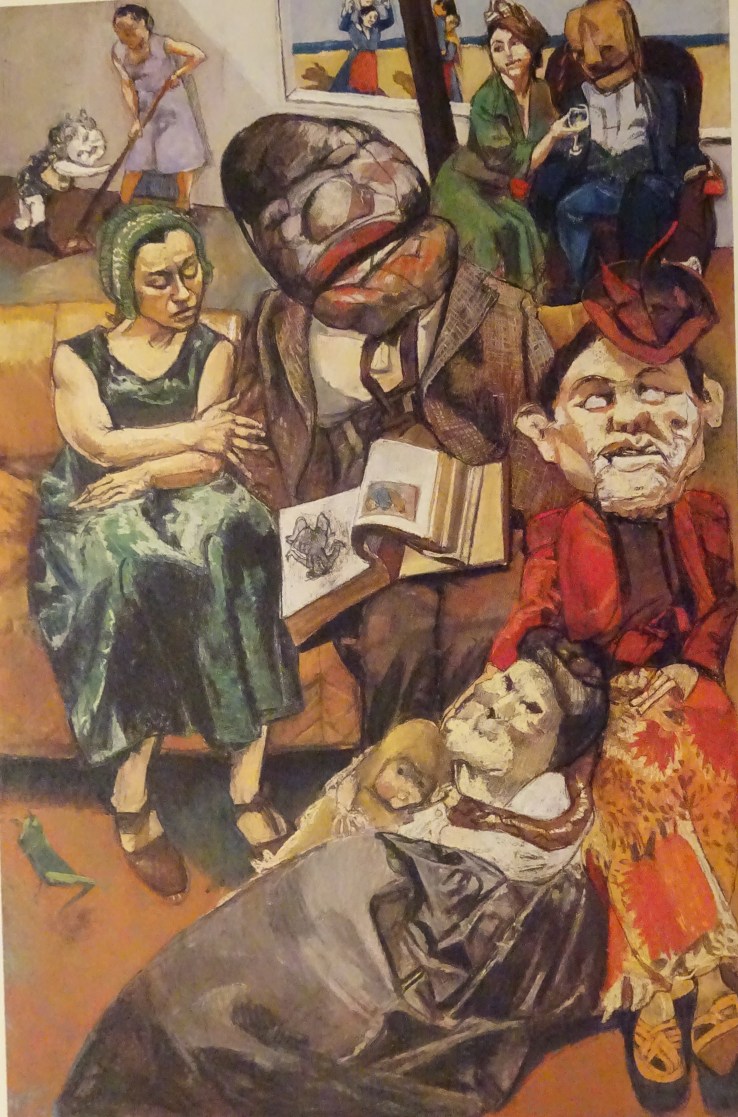

Rego always distorts and updates the originals, infiltrating them with material from her Portuguese childhood deflected through Freud. The grotesque tendency already present in the older writer is raised to a higher pitch. She delights in elements which don’t fit and will never be comfortably assimilated, like suggestions of a Crucifixion in a child’s game on a beach, or a Pieta among the detritus of a box room. Like Bruegel she crams too much into her paintings: one story will rarely suffice and intriguing sub-stories fill up the edges.

There have been unexpected shifts in her career, as in the late 1980s when her husband Victor Willing, also a painter (they met as students at the Slade; the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester is the best place to see his work), was dying, she deserted the folk-material and turned to everyday domestic scenes rendered in flat acrylic of muted, gray-infused hues. The unnerving surreal element of the tales hadn’t disappeared, just retreated out of easy view. Ordinary encounters of family members breathed menace, and predators in frumpy dresses or business suits waited for the right moment to spring.

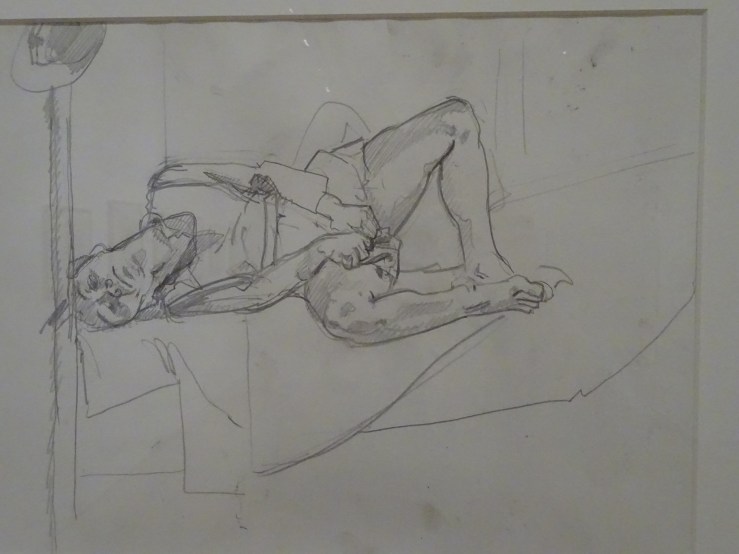

Two of the major shifts in Rego’s method and technique seem to have happened almost by chance: when she stopped smoking, the hand set free could hold the board and she took up drawing more enthusiastically. Finding it awkward to draw herself in complex positions (as The Dog Woman) she recruited her husband’s carer as a model, and observation entered the pictures with new urgency.

In 1994 pastel burst upon the scene as a primary medium for Rego, no longer just a convenience in underdrawing, and has been her preferred medium ever since. Pastel is closer to drawing and makes a violent intensity of colour much easier to achieve, something Rego evidently felt was missing before. Before long some of her pastels reached greater dimensions than her paintings ever had, exceeding 6 feet by 9 in triptychs of the early 2000s. In these gigantic expanses of paper, by far the biggest works in this medium I have ever seen, the monsters return, animal hybrids from fairy tales or primitive religion, and human forms like stuffed animals or vegetable growths.

But all this lies far in the future. What got me started on Paula Rego was the current exhibition of 65 of her drawings at Marlborough London. It covers a relatively short span, 1980-2001, but gives plenty of scope to the fertility of her imagination. The earliest and most delightful examples show animal-headed human figures, more like illustrations in a children’s book than those ominous beings on the walls of Egyptian tombs. But the creatures threaten or crowd each other and collide with toy soldiers half their size. These drawings are forerunners of the apocalyptic opera series (Aida, Carmen, Rigoletto) in acrylic on paper, still looking drawn not painted, like nightmarish comic books 7 feet high where chaos reigns, with pharaohs, crocodiles, local children and bearded female wizards running across the page in uneven tiers. Disproportionate sizes feel relatively innocent here, but loom larger in later Rego compositions as intimidation and enslavement.

But all this lies far in the future. What got me started on Paula Rego was the current exhibition of 65 of her drawings at Marlborough London. It covers a relatively short span, 1980-2001, but gives plenty of scope to the fertility of her imagination. The earliest and most delightful examples show animal-headed human figures, more like illustrations in a children’s book than those ominous beings on the walls of Egyptian tombs. But the creatures threaten or crowd each other and collide with toy soldiers half their size. These drawings are forerunners of the apocalyptic opera series (Aida, Carmen, Rigoletto) in acrylic on paper, still looking drawn not painted, like nightmarish comic books 7 feet high where chaos reigns, with pharaohs, crocodiles, local children and bearded female wizards running across the page in uneven tiers. Disproportionate sizes feel relatively innocent here, but loom larger in later Rego compositions as intimidation and enslavement.

Another drawing in staccato technique like the aftermath of a blast (a detail above) shows a ballerina surrounded by gesturing animals, especially a lobster with raised claws. It dares us to make sense of scattered marks all mastered by centrifugal urges. Even in one of the most composed or statuesque drawings, which shows a girl about to pluck the feathers of a great bird growing from her lap like a mythical hybrid from Ovid, she is both quelling a rival and becoming something unforeseen. Does the cadet in a nearby drawing dominate his sister who is cleaning his boot, or does she emasculate him by keeping him still?

Another drawing in staccato technique like the aftermath of a blast (a detail above) shows a ballerina surrounded by gesturing animals, especially a lobster with raised claws. It dares us to make sense of scattered marks all mastered by centrifugal urges. Even in one of the most composed or statuesque drawings, which shows a girl about to pluck the feathers of a great bird growing from her lap like a mythical hybrid from Ovid, she is both quelling a rival and becoming something unforeseen. Does the cadet in a nearby drawing dominate his sister who is cleaning his boot, or does she emasculate him by keeping him still?

The battered drawing of the Dog Woman was pivotal in Rego’s career. She tried to draw herself in a mirror and found there were parts she just couldn’t see, and from that moment on, live models began to play a larger role in her work. The dog-woman is a compelling translation of the mythic hybrid to a degraded but still powerful creature, making character from humiliation energetically seized and proclaimed. Rego never lets go of the relation between human beings and animals, in its embarrassing nearness and its abysses of otherness.

The battered drawing of the Dog Woman was pivotal in Rego’s career. She tried to draw herself in a mirror and found there were parts she just couldn’t see, and from that moment on, live models began to play a larger role in her work. The dog-woman is a compelling translation of the mythic hybrid to a degraded but still powerful creature, making character from humiliation energetically seized and proclaimed. Rego never lets go of the relation between human beings and animals, in its embarrassing nearness and its abysses of otherness.

There are revealing photos of Rego’s studio set up for one of her large compositions, which show a cascade of actual models, but not live ones, in the very layout familiar to us from the painting. These are the stuffed grotesques that Rego began to use to represent the more monstrous participants in the story. It is disconcerting to learn that her supremely fertile imagination leans on such props. But should it be? Isn’t there something wonderful in replicating the unpredictable creases in the dummy-octopus or the sagging of canvas ticking in the scarecrow’s face? In the later Rego the most fantastic elements are fanatically accurate. This kind of crazy faithfulness would make sense to Bruegel or Bosch. The two versions of the artist’s studio in the Marlborough exhibition are more prosaic than the photos, but show a place similarly full, like the paintings, of discordant life, a place in which the subjects have wills of their own and sometimes push each other out of the way.

There are revealing photos of Rego’s studio set up for one of her large compositions, which show a cascade of actual models, but not live ones, in the very layout familiar to us from the painting. These are the stuffed grotesques that Rego began to use to represent the more monstrous participants in the story. It is disconcerting to learn that her supremely fertile imagination leans on such props. But should it be? Isn’t there something wonderful in replicating the unpredictable creases in the dummy-octopus or the sagging of canvas ticking in the scarecrow’s face? In the later Rego the most fantastic elements are fanatically accurate. This kind of crazy faithfulness would make sense to Bruegel or Bosch. The two versions of the artist’s studio in the Marlborough exhibition are more prosaic than the photos, but show a place similarly full, like the paintings, of discordant life, a place in which the subjects have wills of their own and sometimes push each other out of the way.

Among the most powerful drawings are the series on the touchy (especially in Portugal) subject of Abortion. Even these are not unambiguous. The postures of sexual pleasure and of torment are almost mistakable for each other, momentarily. Here is a subject which does not need to be eked out or amplified by a wealth of surrounding detail.

Among the most powerful drawings are the series on the touchy (especially in Portugal) subject of Abortion. Even these are not unambiguous. The postures of sexual pleasure and of torment are almost mistakable for each other, momentarily. Here is a subject which does not need to be eked out or amplified by a wealth of surrounding detail.

The exhibition verges nearest to the heroic pastels in the largest drawing on view, The Recruit, a neat and self-contained anecdote employing some of the reversals of psychological and sexual valency that Rego enjoys. The woman is shorter and stronger than the man, reveals more of her flesh (a vulnerability) but wears a uniform and carries a stick. The man is larger, but his bigness is pitiful and his gesture unwittingly defensive. How is it that something so absurdly exaggerated seems so evidently true?

The exhibition verges nearest to the heroic pastels in the largest drawing on view, The Recruit, a neat and self-contained anecdote employing some of the reversals of psychological and sexual valency that Rego enjoys. The woman is shorter and stronger than the man, reveals more of her flesh (a vulnerability) but wears a uniform and carries a stick. The man is larger, but his bigness is pitiful and his gesture unwittingly defensive. How is it that something so absurdly exaggerated seems so evidently true?

Naturally, some viewers trace all these revenges and rivalries to the artist’s early experience. But there is a complete disconnect between her recounting of relations in her own family and families as she portrays them. One of the most poignant of all is the Pillowman—Fisherman series (not in the exhibition) where Rego came to think halfway through that the Pillowman represented her much loved father, whom she had never portrayed until then in her work. In the left-hand wing of the Fisherman triptych below, the Pillowman, from Martin McDonagh’s horrific play by that name, is showing a small girl an illustrated book. Paula Rego recognises here the treasured experience of her father reading Dante to her, as he did, setting her on the course her life would follow thereafter. This panel of the triptych incorporates the three parts of the Divine Comedy in an S-curve from top left to bottom right, an order reversed from the way Dante tells it. It is one of Rego’s strangest and boldest transpositions, to represent her father as the hideous Pillowman, a floppy and malleable dummy who kills his numerous child-victims with kindness.

Naturally, some viewers trace all these revenges and rivalries to the artist’s early experience. But there is a complete disconnect between her recounting of relations in her own family and families as she portrays them. One of the most poignant of all is the Pillowman—Fisherman series (not in the exhibition) where Rego came to think halfway through that the Pillowman represented her much loved father, whom she had never portrayed until then in her work. In the left-hand wing of the Fisherman triptych below, the Pillowman, from Martin McDonagh’s horrific play by that name, is showing a small girl an illustrated book. Paula Rego recognises here the treasured experience of her father reading Dante to her, as he did, setting her on the course her life would follow thereafter. This panel of the triptych incorporates the three parts of the Divine Comedy in an S-curve from top left to bottom right, an order reversed from the way Dante tells it. It is one of Rego’s strangest and boldest transpositions, to represent her father as the hideous Pillowman, a floppy and malleable dummy who kills his numerous child-victims with kindness.

Paula Rego drawings at Marlborough London, Albemarle Street W1 until 27 October

Deciphering the spirit in which the Wellcome’s objects were collected would be an absorbing study. A fantastic intent surfaces more than occasionally. Among my favourites were a poster showing the furthest nightmare of a user of the old kind of toothpaste tube that split or fractured easily, resulting in mock carnage that takes unspeakable humanoid form.

Deciphering the spirit in which the Wellcome’s objects were collected would be an absorbing study. A fantastic intent surfaces more than occasionally. Among my favourites were a poster showing the furthest nightmare of a user of the old kind of toothpaste tube that split or fractured easily, resulting in mock carnage that takes unspeakable humanoid form.

Like the Tate, the Wellcome tempts you to keep going when the exhibition is over, straying into other rooms wondering what you will find there, perhaps another instrument of torture, like the early X-ray machine that resembles a treadmill turned on its side

Like the Tate, the Wellcome tempts you to keep going when the exhibition is over, straying into other rooms wondering what you will find there, perhaps another instrument of torture, like the early X-ray machine that resembles a treadmill turned on its side

Most harrowing of all the variations on these themes are a series of dangling victims strung up in the throes of death or its bedraggled aftermath. One of the chickens uncannily resembles a familiar form of ample female nude met in Hellenistic sculpture. This one also appears to crane eagerly upward via a grotesquely elongated neck, at odds with the tranquillity of the torso beneath.

Most harrowing of all the variations on these themes are a series of dangling victims strung up in the throes of death or its bedraggled aftermath. One of the chickens uncannily resembles a familiar form of ample female nude met in Hellenistic sculpture. This one also appears to crane eagerly upward via a grotesquely elongated neck, at odds with the tranquillity of the torso beneath.

![b7 24a 100 [x3] soutine dindon strung up copy 3.jpg](https://robertharbisonsblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/b7-24a-100-x3-soutine-dindon-strung-up-copy-3.jpg?w=739)

The paintings date from 1938 and are late fruits of the Harlem Renaissance. The artist, Jacob Lawrence, had been trained in the art school in Harlem established by the movement, had seen W E B Dubois’ play about Toussaint in 1934 and then researched the subject in the New York Public Library. The series started out as 41 paintings in tempera on paper. It isn’t easy to come by reproductions of the whole set; Lawrence supervised silkscreen prints of 15 of them he considered the best. The painted versions, each only 19 by 11 inches, were used to make the ten huge projections in the British Museum display. They must be something like 9 feet by 5 on the big screen, the size of a large Jackson Pollock, and they support the enlargement brilliantly and become truly heroic images.

The paintings date from 1938 and are late fruits of the Harlem Renaissance. The artist, Jacob Lawrence, had been trained in the art school in Harlem established by the movement, had seen W E B Dubois’ play about Toussaint in 1934 and then researched the subject in the New York Public Library. The series started out as 41 paintings in tempera on paper. It isn’t easy to come by reproductions of the whole set; Lawrence supervised silkscreen prints of 15 of them he considered the best. The painted versions, each only 19 by 11 inches, were used to make the ten huge projections in the British Museum display. They must be something like 9 feet by 5 on the big screen, the size of a large Jackson Pollock, and they support the enlargement brilliantly and become truly heroic images.

There are other Morandis, as well as the whole room of Morandi etchings and drawings from the permanent collection on the top floor. There’s another Sironi landscape of a desolate urban scene crossed by railway tracks with three promising industrial portals in the second Jesi room. This is matched by one upstairs, smaller and even bleaker. Two artists not included in the Brera selection, Medardo Rossi and Renato Guttuso, are also up there, permanently, the first in a richly grimed wax sculpture of a moment glimpsed in a city street, the second in a characteristically crude but gripping work, a dead proletarian hero in a hospital bed. Is it just my imagination or is Guttuso thinking of Mantegna’s similarly foreshortened dead Christ? Guttuso’s shroud is a riot of angular folds and colours—green, purple and ochre all lurking in the monotonous white of the sheets.

There are other Morandis, as well as the whole room of Morandi etchings and drawings from the permanent collection on the top floor. There’s another Sironi landscape of a desolate urban scene crossed by railway tracks with three promising industrial portals in the second Jesi room. This is matched by one upstairs, smaller and even bleaker. Two artists not included in the Brera selection, Medardo Rossi and Renato Guttuso, are also up there, permanently, the first in a richly grimed wax sculpture of a moment glimpsed in a city street, the second in a characteristically crude but gripping work, a dead proletarian hero in a hospital bed. Is it just my imagination or is Guttuso thinking of Mantegna’s similarly foreshortened dead Christ? Guttuso’s shroud is a riot of angular folds and colours—green, purple and ochre all lurking in the monotonous white of the sheets. The biggest painting in the second Brera room is Mario Mafai‘s Butchered Ox which shows two oxen rendered in what the label calls an ‘intensely expressive and emotionally painterly style.’ But I had to put Soutine’s much wilder versions of the same subject out of my mind to enjoy the abandon of this one. The catalogue prints Butchered Ox upside down. The tradition of inverting modern paintings, deliberately or inadvertently, is a venerable one.

The biggest painting in the second Brera room is Mario Mafai‘s Butchered Ox which shows two oxen rendered in what the label calls an ‘intensely expressive and emotionally painterly style.’ But I had to put Soutine’s much wilder versions of the same subject out of my mind to enjoy the abandon of this one. The catalogue prints Butchered Ox upside down. The tradition of inverting modern paintings, deliberately or inadvertently, is a venerable one.