Every year in the early spring they mount a display of orchids in a greenhouse at Kew. This year it was Colombia’s turn, and around 6000 blooms of 150 South American species were crowded together in three different artificial climates under a single cascading structure resembling a landscape-form in steel and glass. The exhibition drew large numbers in search of beauty, oddity and natural diversity, who had to wait their turn at busy times of day, like bees clustering round a popular shrub.

What or who are orchids for?

In one sense they’re the commonest plant and at the same time among the rarest. They’ve spread everywhere and diversified into the largest number of distinct species (around 26,000) of any botanical tribe.

Yet they’re impossibly anomalous among plants, with some of the strangest life cycles of all, including parasitism and deceit, bizarre structures of great complexity seemingly designed simply to plant lumps of pollen on the head or tail of males of a chosen insect species. Many orchid species are not rooted in earth, but attach themselves to jungle trees and dangle their roots in air, ‘roots’ which do root-jobs of absorbing nutrients but violate the main meanings of the word, a kind of botanical outrage.

Worst or most wonderful of all is what orchids do to their pollinators. Here exaggeration and deceit go together. Nectar or food or sexual gratification which doesn’t actually exist seems to require more grandiose sacs or pouches or replicas of the female insect in order to seduce the victim or dupe (what should we call him?). Even now moral disapproval creeps into descriptions of orchid ‘contrivances’, promising rewards but giving none. Charles Darwin, one of the most acute of early students of orchid pollination, couldn’t believe that orchids really had no nectar for their visitors, or that this was a system that would work.

A suspicion lingers that orchids have fooled their human enthusiasts as well, luring them with complex forms that violate established norms of size and proportion and instil suggestions of resemblance to all sorts of non-botanical forms, so that, like the wasps, the orchid’s human fans are mistaking the blooms unconsciously for something else.

Popular names of orchids go on expressing the ancient folk-view that there are deep sympathies between the lives of human beings and those of plants. Modern names like ‘fried-egg orchid’ often stick out by their starkly comic intention; in Shakespeare even the most grotesque flower names, like ‘dead man’s beard’, feel like something more than a joke.

‘Slipper’ orchids are not diminished by the name, which conjures up spaces of myth, into which victims fall in search of food and will only get out by doing the plant’s bidding, collaborating in the orchid’s plans for its own continuance. It feels absurd to talk as if we believed in the orchid’s agency, but it becomes more and more feasible to assume the intelligence of plants (see Colin Fudge on trees), insects (especially ants, bees and termites, including many pollinators) or birds (astonishing recent research on birds’ brains). And the stories people have told about plants couldn’t be more preposterous than the dramas acted out in the innermost chambers of certain orchid blooms.

But to see, or even to imagine, these Piranesian spaces you probably need to blow up a photograph of an orchid interior to approximate the bee’s-eye view and then you tell yourself that you are approaching the true essential meaning of the orchid. At Kew I picked up The Book of Orchids, a life-size guide to 600 species from around the world illustrated with one photo of each, or sometimes with two copies of the same photo, one large and one small. I assumed that the small one was life-size and the big was a blow-up which let you see richness and complexity invisible to normal human sight. This is often but not always what the relation between the two photos is. Sometimes the little one shows the whole bloom for the first time, because this orchid is too big to fit onto the page-size chosen for this book.

Six hundred orchids has a magical sound, but the speed of the survey inevitably produces vertigo, and taking in so many almost requires isolating the blooms from their surroundings, and even from the stems and the leaves of their own plants. So you have cut-outs of the most compelling feature, a single flower, the orchid as logo, more or less. Some orchids, like the slippers, do occur singly in the wild or at least widely spaced on the stem, but these are likely to be the heavier blooms, which would drag the plant down in clusters.

To understand orchid structure you probably need to isolate single blooms in this way, maybe even render them artfully through drawings. To see many actual examples on a single occasion you need to create something like a museum-situation, which if you’re lucky, as for example at Kew, will also feel like a habitat, a constructed jungle. Some orchids will sit in pots on the ground, but others will appear to have attached themselves to trees and spread their roots in air, far out of reach.

There’s a limit though, and some of the most precious, like most of the slippers, will appear behind glass to protect them from the attentions of the orchid-lovers. And if proof were needed, moving from cool and dry to hot and wet climates simply by opening and closing a door reminds you that you are crossing distances that would consume whole days outside the botanical museum.

So you continue your trip through this spectacle of the world’s diversity which is more like a visit to the National Gallery than an hour in an actual jungle. And the deepest involvement requires further manipulation of the images collected on the ‘journey’, carried out afterward at home, where you are continually noticing features that there was no way you could see on the spot, because you couldn’t isolate each bloom like a painting or take the time to walk round it like a sculpture. In certain respects the fullest plant museum exists only on a screen, best of all that of a small laptop, not a large television which cannot focus the subject or your attention nearly so tellingly.

Surface patterns are among the most startling and mesmerising features of these blooms, endlessly attractive in a literal sense—the eye is helplessly drawn to them. Under magnification they become something different and then we can imagine the disorienting effect on the insect trying to keep its balance in the maelstrom of a centrifugal pattern which disperses itself more violently as you move in nearer. Petals and sepals that all look much the same to the human eye are strongly differentiated when magnified and depict radically different kinds of fragmentation, one alarming, the other reassuring. Seen close up, the overall effect is much more directional and thus coercive.

In this species blooms often present themselves ‘upside down’ or cockeyed, meaning that to experience their symmetry or to recognise the typical orchid structure of three petals overlaid (in reverse) on three sepals, making a six-pointed figure, you need to reorient yourself bodily, and this leads us to imagine insects making aesthetic choices as they land on orchids.

In this species blooms often present themselves ‘upside down’ or cockeyed, meaning that to experience their symmetry or to recognise the typical orchid structure of three petals overlaid (in reverse) on three sepals, making a six-pointed figure, you need to reorient yourself bodily, and this leads us to imagine insects making aesthetic choices as they land on orchids.

Other, blotchier patterns look to human eyes like stippling, a technique not a purely random occurrence, blobs trying to come together rather than simply spreading themselves, a focusing effect to which it would be hard to pay no attention at all. Is such visual complexity of no consequence to the insect, and the watercolour-like variations in intensity as you move from the centre to the edge of each blob? Human beings see faces everywhere, especially in whole classes of plant blooms. Is it fanciful to imagine insects having similar susceptibilities to certain combinations of dots, lines and concentrated forms? Not that we could easily guess what they remind the insect of, just that this sort of unconscious memory might be taking place.

Darwin was fascinated by insects’ responses to colour, a subject which goes on provoking research and remains almost as much of a mystery as ever, as is also the human response to colour in plants, though studied more thoroughly and for much longer.

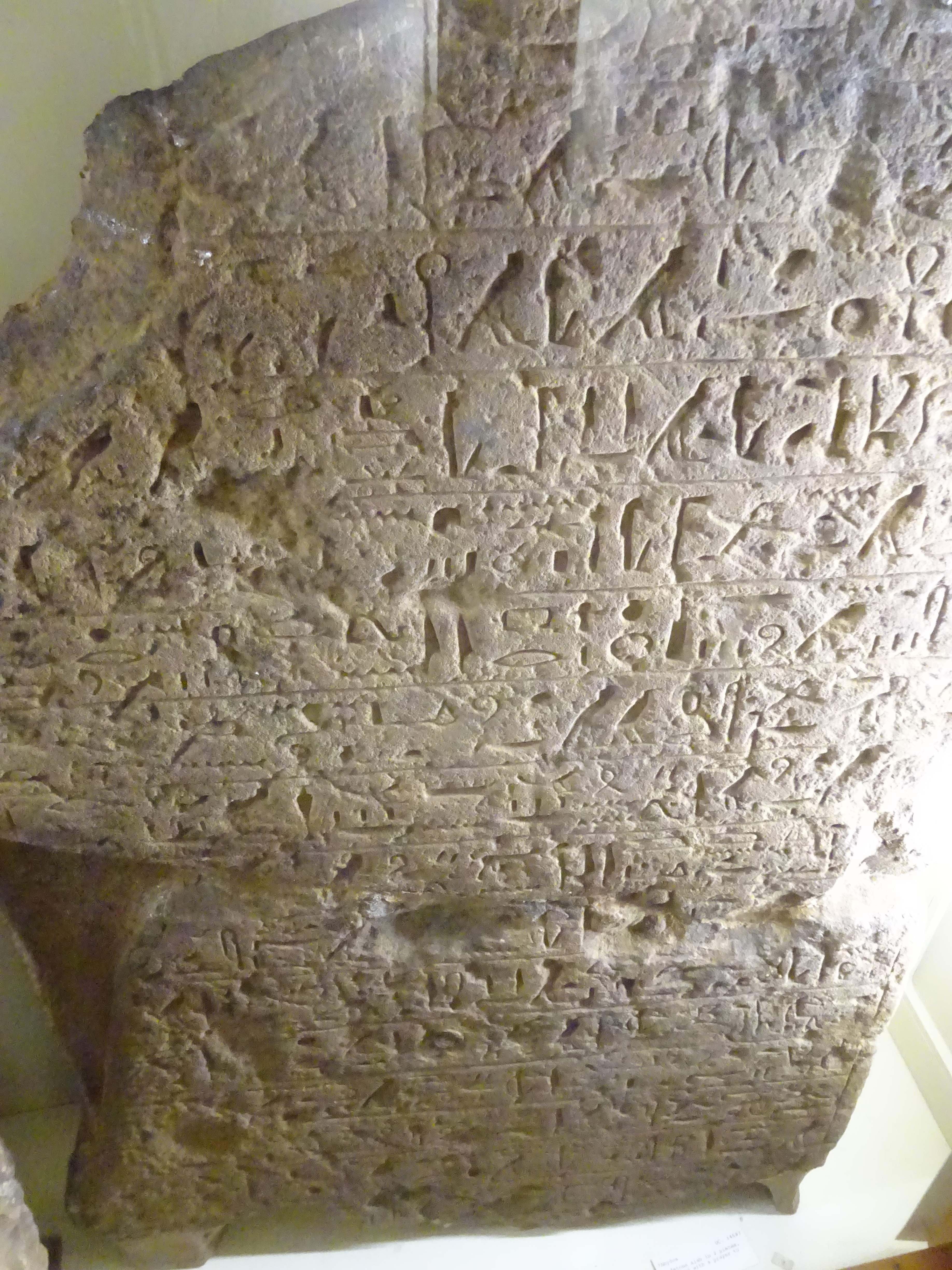

Human beings are also prone to see writing where there is none, in vegetable scribbling on leaves or tree bark. Some of the strangest surface pattern on orchids has evidently suggested lines of letters in a genus labeled ‘grammatophyllum’, which seems made to be puzzled over, trying to read something into the sequence of marks. Ruskin was always imagining that the world put a certain natural feature in front of him to say something meant specifically for him, perhaps a late, narcissistic rendition of the old belief that the Creator meant for us to find lessons in stones and instruction in storms. Watered down enough, something like this must be taking place in many people’s conversations with orchids, in spite of idealists like Kant who used flowers to preach purposiveness without a purpose.

There is such diversity in orchids that we couldn’t possibly do justice to it here or anywhere else. There are the forms that for some personal reason disgust us, because they remind us of varicose veins or toothless mouths. There are orchids which don’t look like flowers at all, like the wonderful freaks called spider orchids, not because they actually look like spiders, but because they have long, ungainly features, and more than a few of them. Visually similar are around six species, two of whose sepals go on extending themselves from the main bloom until they hit a hard surface, thus producing streamers several feet long. I have captured only a junior version of this.

There are furly copper-coloured species that perform the unnerving feat of turning themselves inside out, none of whose elements you can convince to stop shuddering, an insect-sized version of Baroque movement. And there is another orchid so magically translucent it is hard to believe it is alive and not something created just to show off certain properties of light, a task of too-refined focus to be entrusted to a creature. This species also exhibits one of the most high-handed divergences of sepals and petals, which now form two independent whorls, petals fused into one and sepals floating free, with nothing in common between them except that they are joined at the hip.

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.

Next to it is another fallen figure who raises a little shield as he falls. His legs are pitifully shrunken, his torso misshapen like a rock which won’t bend itself completely to the human form. His head is more rudimentary than other Frinks, a stalk, an eye, a flat disk. I’m trying to take in the unmanageable variety of aspects I find in these forms, the great advantage of sculpture, that it can be a dozen different works in succession, depending on where you’re standing, or not standing but circling.

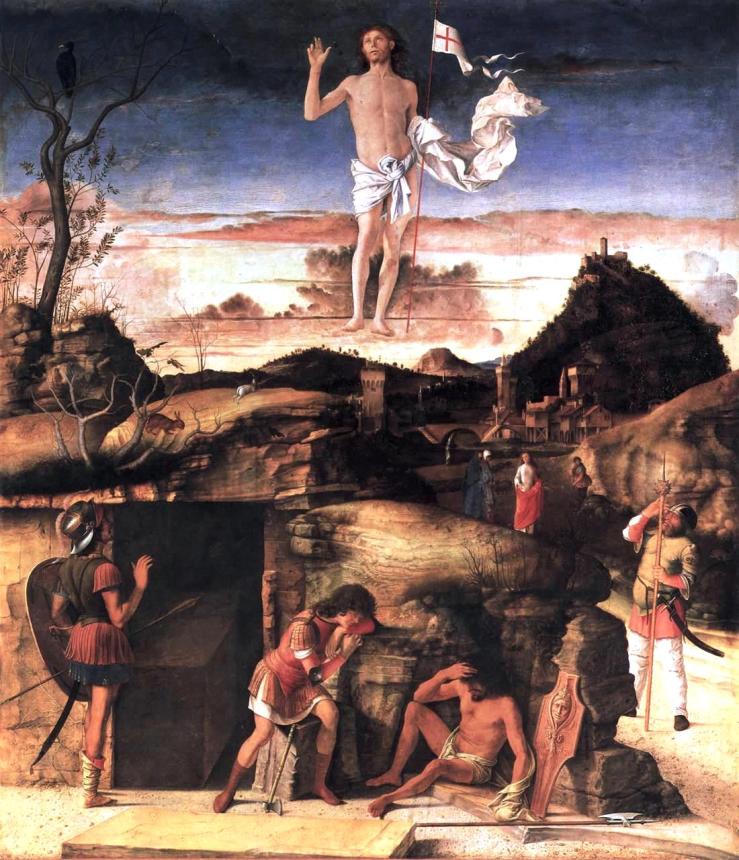

Two fascinating drawings stood in for the absent painting, one with the three Maries bent over the prone figure in something like the Milan position, with feet pointing toward the viewer (actually at c 25 degrees angled left). Then, most surprisingly, another Christ is included, pointing the other way, at the same deflection to the right. The two dead bodies are parallel and would touch if the one further away were not raised a foot off the ground the nearer body lies on. It verges on two bodies trying to inhabit the same space, or slotting together like a puzzle.

Two fascinating drawings stood in for the absent painting, one with the three Maries bent over the prone figure in something like the Milan position, with feet pointing toward the viewer (actually at c 25 degrees angled left). Then, most surprisingly, another Christ is included, pointing the other way, at the same deflection to the right. The two dead bodies are parallel and would touch if the one further away were not raised a foot off the ground the nearer body lies on. It verges on two bodies trying to inhabit the same space, or slotting together like a puzzle.

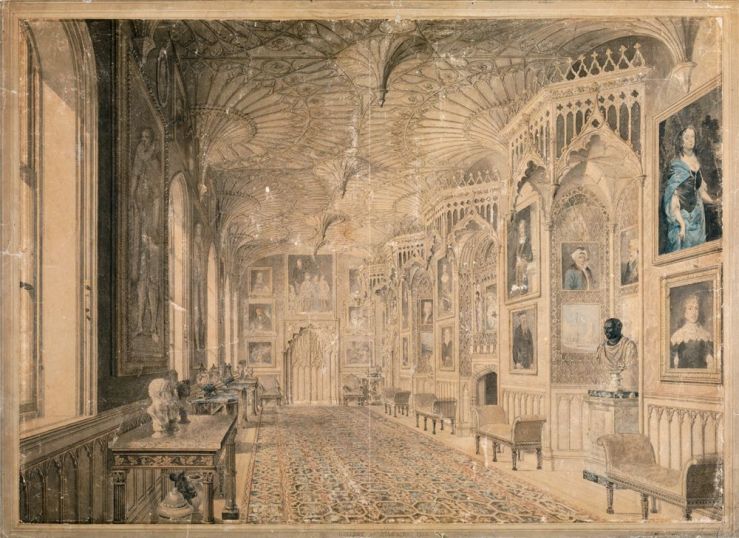

Museums are usually more accommodating, making you think you are getting somewhere, but here there’s no overarching narrative, only a tremendous crowd of separate things. I got the idea I should write about the Petrie in the first flush of my enthusiasm, preserving the exact state of my current ignorance, before I’d read any further in the two books I got there and found out more. This would give me a chance to test a favourite theory, according to which I’ll do damage by burdening myself with learning, like a burrowing animal going further into darkness.

Museums are usually more accommodating, making you think you are getting somewhere, but here there’s no overarching narrative, only a tremendous crowd of separate things. I got the idea I should write about the Petrie in the first flush of my enthusiasm, preserving the exact state of my current ignorance, before I’d read any further in the two books I got there and found out more. This would give me a chance to test a favourite theory, according to which I’ll do damage by burdening myself with learning, like a burrowing animal going further into darkness.

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Around them were grouped embellishments of canoes: splashboards inscribed with wave patterns that turn into birds biting each other, or a menacing crocodile prow with a demonic face on a canvas shield looming over it (see opening image). There were also three navigation charts like a cross between maps and abstract art, made of sticks (the main stems of coconut-palm fronds) lashed together into lattices dotted with tiny shells tied on in asymmetrical sequences. It’s the asymmetry and minimal means that make them feel like abstract art, and the diagrammatic arrangements of lines and dots that recall maps.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Flimsiness, undependable materials and the prospect of a short life can also lead to delightfully casual effects, as they do in barkcloth masks stretched on light bamboo frames which are hard to control precisely. The resulting wobbliness of forms can look like beings who are changing shape before your eyes, as in the lopsided duck or bird above, who seems to make space for a large spider living on his forehead at the centre of a web that covers the bird’s face. Its enormous eyes are not used for looking at the everyday world but at something further off. The wearer can see only through the bird’s beak, which must give everyone, dancer and spectator alike, a dislocated idea of where reality will be found.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of.

Tattoos, and especially Maori face-tattoos, are indisputably an art-form, but difficult to include in an exhibition consisting of objects anchored in one place. There’s a remarkable drawing made in England in 1818 by a Maori artist suffering climate and culture shock. He depicts his brother’s face-tattoo as a single exploded view which flattens out the parts of the design that would disappear around the corners on the cheeks or over the top of the forehead. He makes it easier to grasp how this process consumes a part of the body and transforms it into a work of art, or rather how the body and the design are fused into a new being and a new work, a deeper idea of what writing lines on the body might achieve than most tattooists dream of. In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving.

In 1896 a museum director in New Zealand solved the problem of how to display tattoos in a gallery that conveyed their vividness and power. He commissioned a sculpture from a noted Maori artist that would give him a three-dimensional rendering of tattoos. The resulting work looks as if it is carved from a single piece of dark wood left largely uncoloured to represent with defiant strength the darkness of native New Zealand skin. It shows three fully rounded heads emerging from a flat background deeply carved with traditional patterns, stained red and including two fierce birds with mother of pearl eyes. The heads are arranged in rows, two men at the top, a woman at the bottom. The men stare straight ahead, sightlessly; the woman looks down but her eyes are closed. You can study the tattoos as the director intended, but the expressions of the three and their asymmetries are unnerving. There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within.

There is often a strong impulse in Oceanic art to dissolve solid bodies and obliterate the distinctness of forms. One of the most perplexing works shows a human body become almost two dimensional, a graphic squiggle of concentric curvelets enclosing an essence receding toward the status of a dot. In a world without writing there is no letter C, but in a world with drawing there is certainly this empty but enclosing form of a shallow curve with more copies of itself within. In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

In the same company belongs the astonishingly featureless figure from Nukuoro in the Carolines whose head is a spinning top like one of Oscar Schlemmer’s, spherical at the back, narrowed to the point of a cone at the front, its chin. I imagine that I see on this ‘face’ the most delicate concentric tattoos and even almond-shaped openings in the pattern for the eyes. From Tahiti comes another way of blanking out the person with strong shapes and textures, ones which do not belong to personhood, large flat pearly shells instead of face, hands and breasts; stiff rectangles of alien substances covering the rest of the body. Appropriately this is a costume for the chief mourner at a funeral, someone who cuts off from all connection while the ordeal lasts.

Recentness might also seem to count for too much in some of the most venerable exhibits, like the Binham Hoard or the Harford Farm Brooch, both named for the spots in Norfolk where they were dug up. In the series of recent finds we see the soil of England continually yielding up signs of the Anglo Saxons, and making us feel that they are in some sense still there.

Recentness might also seem to count for too much in some of the most venerable exhibits, like the Binham Hoard or the Harford Farm Brooch, both named for the spots in Norfolk where they were dug up. In the series of recent finds we see the soil of England continually yielding up signs of the Anglo Saxons, and making us feel that they are in some sense still there.

The best or the worst tangle in the exhibition occurs on the famous gold belt- buckle from Sutton Hoo, appropriately because a buckle makes knots in a belt unnecessary, so the buckle is free to illustrate knots of insoluble complexity. The catalogue likens the Anglo Saxon taste for linear intricacy to the love of riddles, and praises the goldsmith for his clever devices for sorting out the puzzle. The buckle apparently depicts 13 bird-headed, snake-bodied beasts at three different scales, four of which are used up in the hook and clasp, leaving 9 for the main plate, where the writhing bodies are distinguished by different types of beading (only two of these, not nine, as far as I can see). I am left wondering whether this buckle is a riddle with or without a solution. I see the animals’ bodies and once in a while their paws, but not their heads, which have become so minimal they’re more like paper clips than animal parts, so that identifying them gives no pleasure. Perhaps this is the final test of a taste for puzzles: you need to like the ones which can’t be solved.

The best or the worst tangle in the exhibition occurs on the famous gold belt- buckle from Sutton Hoo, appropriately because a buckle makes knots in a belt unnecessary, so the buckle is free to illustrate knots of insoluble complexity. The catalogue likens the Anglo Saxon taste for linear intricacy to the love of riddles, and praises the goldsmith for his clever devices for sorting out the puzzle. The buckle apparently depicts 13 bird-headed, snake-bodied beasts at three different scales, four of which are used up in the hook and clasp, leaving 9 for the main plate, where the writhing bodies are distinguished by different types of beading (only two of these, not nine, as far as I can see). I am left wondering whether this buckle is a riddle with or without a solution. I see the animals’ bodies and once in a while their paws, but not their heads, which have become so minimal they’re more like paper clips than animal parts, so that identifying them gives no pleasure. Perhaps this is the final test of a taste for puzzles: you need to like the ones which can’t be solved.

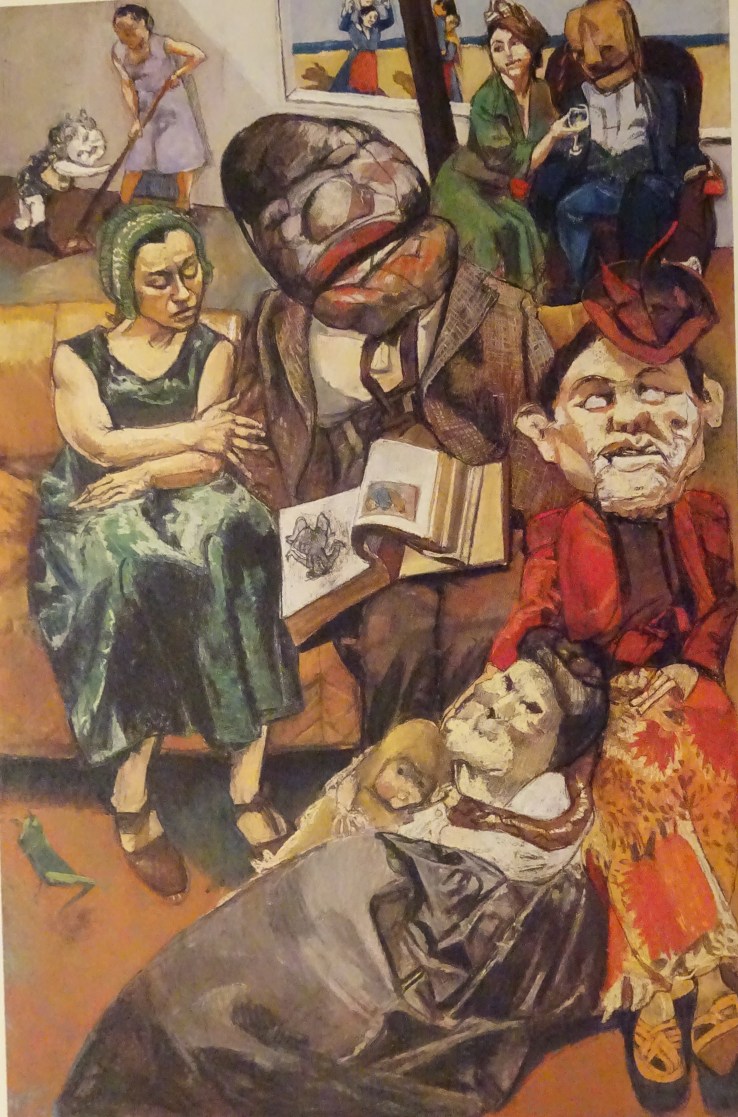

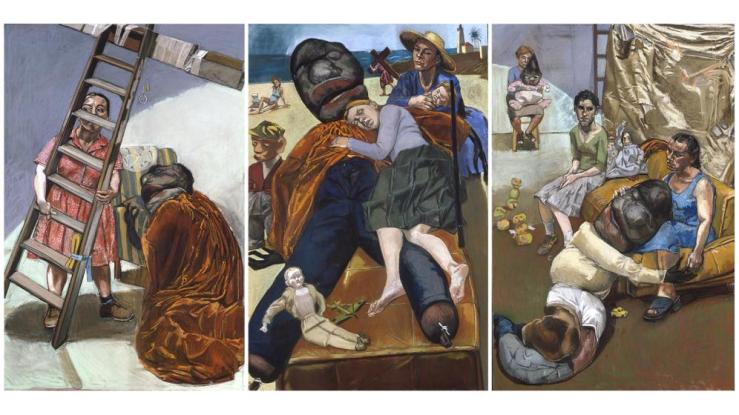

Paula Rego is another outlier in the territory of contemporary art. She is Portuguese but came to London to study and now lives there. In some way she is more like a nineteenth-century novelist than a twenty-first century painter. She seems drawn to other painters for their subject matter rather than their handling of paint. Hogarth, Goya and James Ensor turn up in her comments about her own work, which often takes a literary work as the starting point, The Sin of Father Amaro (a scandalous Portuguese novel of 1875), Jane Eyre, Portuguese folk tales, English nursery rhymes, or a dark play by the British-Irish writer Martin McDonagh.

Paula Rego is another outlier in the territory of contemporary art. She is Portuguese but came to London to study and now lives there. In some way she is more like a nineteenth-century novelist than a twenty-first century painter. She seems drawn to other painters for their subject matter rather than their handling of paint. Hogarth, Goya and James Ensor turn up in her comments about her own work, which often takes a literary work as the starting point, The Sin of Father Amaro (a scandalous Portuguese novel of 1875), Jane Eyre, Portuguese folk tales, English nursery rhymes, or a dark play by the British-Irish writer Martin McDonagh. But all this lies far in the future. What got me started on Paula Rego was the current exhibition of 65 of her drawings at Marlborough London. It covers a relatively short span, 1980-2001, but gives plenty of scope to the fertility of her imagination. The earliest and most delightful examples show animal-headed human figures, more like illustrations in a children’s book than those ominous beings on the walls of Egyptian tombs. But the creatures threaten or crowd each other and collide with toy soldiers half their size. These drawings are forerunners of the apocalyptic opera series (Aida, Carmen, Rigoletto) in acrylic on paper, still looking drawn not painted, like nightmarish comic books 7 feet high where chaos reigns, with pharaohs, crocodiles, local children and bearded female wizards running across the page in uneven tiers. Disproportionate sizes feel relatively innocent here, but loom larger in later Rego compositions as intimidation and enslavement.

But all this lies far in the future. What got me started on Paula Rego was the current exhibition of 65 of her drawings at Marlborough London. It covers a relatively short span, 1980-2001, but gives plenty of scope to the fertility of her imagination. The earliest and most delightful examples show animal-headed human figures, more like illustrations in a children’s book than those ominous beings on the walls of Egyptian tombs. But the creatures threaten or crowd each other and collide with toy soldiers half their size. These drawings are forerunners of the apocalyptic opera series (Aida, Carmen, Rigoletto) in acrylic on paper, still looking drawn not painted, like nightmarish comic books 7 feet high where chaos reigns, with pharaohs, crocodiles, local children and bearded female wizards running across the page in uneven tiers. Disproportionate sizes feel relatively innocent here, but loom larger in later Rego compositions as intimidation and enslavement. Another drawing in staccato technique like the aftermath of a blast (a detail above) shows a ballerina surrounded by gesturing animals, especially a lobster with raised claws. It dares us to make sense of scattered marks all mastered by centrifugal urges. Even in one of the most composed or statuesque drawings, which shows a girl about to pluck the feathers of a great bird growing from her lap like a mythical hybrid from Ovid, she is both quelling a rival and becoming something unforeseen. Does the cadet in a nearby drawing dominate his sister who is cleaning his boot, or does she emasculate him by keeping him still?

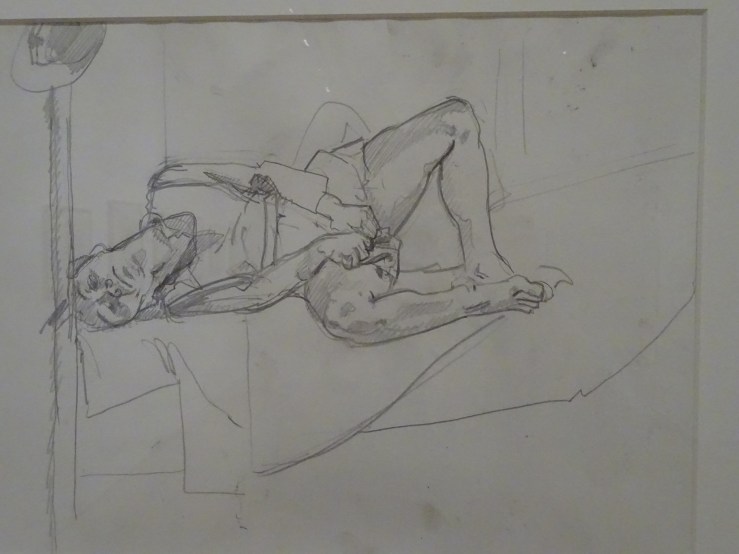

Another drawing in staccato technique like the aftermath of a blast (a detail above) shows a ballerina surrounded by gesturing animals, especially a lobster with raised claws. It dares us to make sense of scattered marks all mastered by centrifugal urges. Even in one of the most composed or statuesque drawings, which shows a girl about to pluck the feathers of a great bird growing from her lap like a mythical hybrid from Ovid, she is both quelling a rival and becoming something unforeseen. Does the cadet in a nearby drawing dominate his sister who is cleaning his boot, or does she emasculate him by keeping him still? The battered drawing of the Dog Woman was pivotal in Rego’s career. She tried to draw herself in a mirror and found there were parts she just couldn’t see, and from that moment on, live models began to play a larger role in her work. The dog-woman is a compelling translation of the mythic hybrid to a degraded but still powerful creature, making character from humiliation energetically seized and proclaimed. Rego never lets go of the relation between human beings and animals, in its embarrassing nearness and its abysses of otherness.

The battered drawing of the Dog Woman was pivotal in Rego’s career. She tried to draw herself in a mirror and found there were parts she just couldn’t see, and from that moment on, live models began to play a larger role in her work. The dog-woman is a compelling translation of the mythic hybrid to a degraded but still powerful creature, making character from humiliation energetically seized and proclaimed. Rego never lets go of the relation between human beings and animals, in its embarrassing nearness and its abysses of otherness. There are revealing photos of Rego’s studio set up for one of her large compositions, which show a cascade of actual models, but not live ones, in the very layout familiar to us from the painting. These are the stuffed grotesques that Rego began to use to represent the more monstrous participants in the story. It is disconcerting to learn that her supremely fertile imagination leans on such props. But should it be? Isn’t there something wonderful in replicating the unpredictable creases in the dummy-octopus or the sagging of canvas ticking in the scarecrow’s face? In the later Rego the most fantastic elements are fanatically accurate. This kind of crazy faithfulness would make sense to Bruegel or Bosch. The two versions of the artist’s studio in the Marlborough exhibition are more prosaic than the photos, but show a place similarly full, like the paintings, of discordant life, a place in which the subjects have wills of their own and sometimes push each other out of the way.

There are revealing photos of Rego’s studio set up for one of her large compositions, which show a cascade of actual models, but not live ones, in the very layout familiar to us from the painting. These are the stuffed grotesques that Rego began to use to represent the more monstrous participants in the story. It is disconcerting to learn that her supremely fertile imagination leans on such props. But should it be? Isn’t there something wonderful in replicating the unpredictable creases in the dummy-octopus or the sagging of canvas ticking in the scarecrow’s face? In the later Rego the most fantastic elements are fanatically accurate. This kind of crazy faithfulness would make sense to Bruegel or Bosch. The two versions of the artist’s studio in the Marlborough exhibition are more prosaic than the photos, but show a place similarly full, like the paintings, of discordant life, a place in which the subjects have wills of their own and sometimes push each other out of the way. Among the most powerful drawings are the series on the touchy (especially in Portugal) subject of Abortion. Even these are not unambiguous. The postures of sexual pleasure and of torment are almost mistakable for each other, momentarily. Here is a subject which does not need to be eked out or amplified by a wealth of surrounding detail.

Among the most powerful drawings are the series on the touchy (especially in Portugal) subject of Abortion. Even these are not unambiguous. The postures of sexual pleasure and of torment are almost mistakable for each other, momentarily. Here is a subject which does not need to be eked out or amplified by a wealth of surrounding detail. The exhibition verges nearest to the heroic pastels in the largest drawing on view, The Recruit, a neat and self-contained anecdote employing some of the reversals of psychological and sexual valency that Rego enjoys. The woman is shorter and stronger than the man, reveals more of her flesh (a vulnerability) but wears a uniform and carries a stick. The man is larger, but his bigness is pitiful and his gesture unwittingly defensive. How is it that something so absurdly exaggerated seems so evidently true?

The exhibition verges nearest to the heroic pastels in the largest drawing on view, The Recruit, a neat and self-contained anecdote employing some of the reversals of psychological and sexual valency that Rego enjoys. The woman is shorter and stronger than the man, reveals more of her flesh (a vulnerability) but wears a uniform and carries a stick. The man is larger, but his bigness is pitiful and his gesture unwittingly defensive. How is it that something so absurdly exaggerated seems so evidently true? Naturally, some viewers trace all these revenges and rivalries to the artist’s early experience. But there is a complete disconnect between her recounting of relations in her own family and families as she portrays them. One of the most poignant of all is the Pillowman—Fisherman series (not in the exhibition) where Rego came to think halfway through that the Pillowman represented her much loved father, whom she had never portrayed until then in her work. In the left-hand wing of the Fisherman triptych below, the Pillowman, from Martin McDonagh’s horrific play by that name, is showing a small girl an illustrated book. Paula Rego recognises here the treasured experience of her father reading Dante to her, as he did, setting her on the course her life would follow thereafter. This panel of the triptych incorporates the three parts of the Divine Comedy in an S-curve from top left to bottom right, an order reversed from the way Dante tells it. It is one of Rego’s strangest and boldest transpositions, to represent her father as the hideous Pillowman, a floppy and malleable dummy who kills his numerous child-victims with kindness.

Naturally, some viewers trace all these revenges and rivalries to the artist’s early experience. But there is a complete disconnect between her recounting of relations in her own family and families as she portrays them. One of the most poignant of all is the Pillowman—Fisherman series (not in the exhibition) where Rego came to think halfway through that the Pillowman represented her much loved father, whom she had never portrayed until then in her work. In the left-hand wing of the Fisherman triptych below, the Pillowman, from Martin McDonagh’s horrific play by that name, is showing a small girl an illustrated book. Paula Rego recognises here the treasured experience of her father reading Dante to her, as he did, setting her on the course her life would follow thereafter. This panel of the triptych incorporates the three parts of the Divine Comedy in an S-curve from top left to bottom right, an order reversed from the way Dante tells it. It is one of Rego’s strangest and boldest transpositions, to represent her father as the hideous Pillowman, a floppy and malleable dummy who kills his numerous child-victims with kindness.