Something catches your eye that you’ve passed many times without seeing. Why now, suddenly?

The suddenness is wonderful and the work completely absorbing. In order to see it at all you have to block out a lot else, a diverting cacophony of other works, a jumble of forms and sizes never meant to be seen together, apparently assembled to no coordinate plan. That’s the beauty of the V & A Cast Court, of course, a host of juxtapositions only permissible because nothing here is real.

But once you’ve singled one out, the unreality doesn’t count. The plaster isn’t dirty, but it isn’t clean—it does a reasonable job of imitating the worn and mottled look of marble. Sometimes there are signs of its having been coloured—mostly with stone colours, grey and brown. By a fortuitous twist, the roughness of plaster and traces of varnish suit this particular sculptor uncannily well, who was one of the first carvers to make something positive and expressive of irregularity and even of flaws in execution.

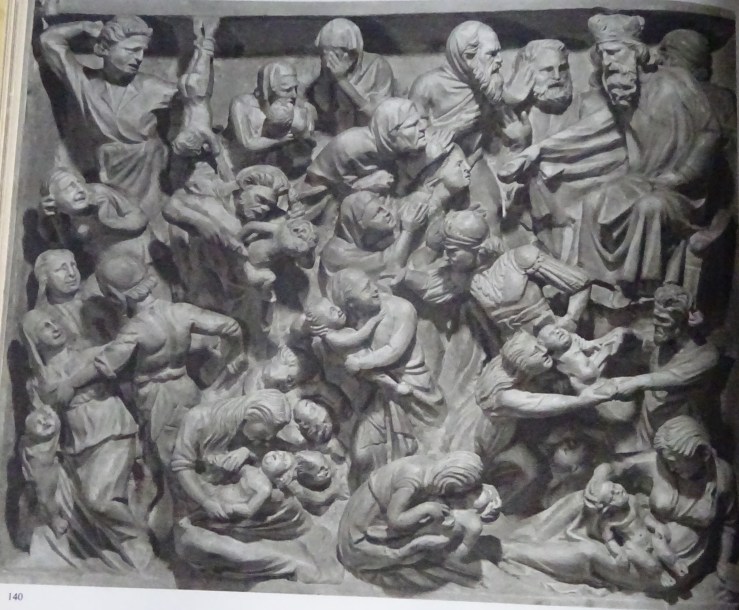

Above all, my new favourite is a conglomerate and the separate parts aren’t precious individually. Not that there aren’t wonderful strokes of invention and plenty of arresting details. On that day it seemed the most gripping large work of sculpture in the world, challenging one of the most powerful plastic statements ever, the great altar at Pergamon, which it couldn’t match for scale and violence, but in narrative variety maybe it came out ahead and had the giddy spectator reaching for parallels like the dramatic profusion of all the novels of Balzac.

The work I am looking at is Giovanni Pisano’s pulpit for Pisa cathedral executed in 1302-10 with a fair amount of studio help, a fact which makes some critics compare it unfavourably with an earlier, overlapping project by the same sculptor, a pulpit for the parish church of S Andrea in Pistoia, much smaller than this later work, with more of Giovanni’s own carving in the intimate reliefs, which are placed, as they are in Pisa, furthest from the observer.

It seems that Pisano may have learned from the earlier experiment that the small scale work was somewhat thrown away when mounted well above head-height. So in Pisa he painted with a broader brush and put his energy into a greater proliferation of larger figures at ground level. That is where the best invention occurs in the Pisa pulpit.

Pulpit is a seriously demeaning name for this marvelous crowd of carved figures who form a cross between a forest and a pavilion full of sculptural movement.

The whole is cylindrical in form, with a richly carved roof (the wide band that contains the reliefs) supported on 8 peripheral columns which converge on a single central support. There is a curving stair for reaching the roof attached to one end, the route which priests and deacons would use to turn the large construction into a humble pulpit, as if its whole purpose was to give them an elevated perch from which to teach and preach.

The phenomenal sculptural energy of the assemblage devotes itself to disguising the supporting columns with an ingenious set of caryatid-like beings. In two cases these are single human figures on pedestals who allow capitals to be planted on their heads.

In the most thrilling instances – two of them, adjacent – a larger figure appears to bear the brunt but is surrounded by a crowd of four figures approaching life size. These two clusters are the most gripping or enigmatic elements of the whole, one composed of women, the other of men, many of them carrying emblematic objects, like a set of scales or a dead lion suspended upside down. The men are all accompanied by their daemons, three winged animals and an angel.

The moments before you figure out or are told what any of this means are precious, and something to hold onto, even after you have identified the four medium-sized women as Virtues and the four men as Evangelists, the larger female figure dominating the others not Charity – she suckles two infants – but Ecclesia, the Church, and the larger man, Christ.

At the V & A Ecclesia has lost one of her main accoutrements, a big dove that whispers aggressively in her ear. This idea of inspiration from above occurs repeatedly in the smaller series of sibyls at the level of spandrels supporting the reliefs, one of which (in Pistoia) looks like the inspiration in turn of a memorable sibyl by Michelangelo on the Sistine ceiling. Ecclesia may have got separated from her dove after the fire of 1595 when the pulpit was taken to pieces and radically deconstructed, when the parts got scrambled and relations between them were lost, at a time when other sculptural elements probably disappeared. Interest in returning the pulpit to its original state grew in the 1860s, around the time this cast was made. The current presentation of the work in Pisa (seen further below) dates from Bacci’s reconstruction of 1926.

There are many satisfying symmetries buried in the scheme, one female nude and one male, the one based on a famous classical type of modest Venus, now representing Temperance (work out how), the other an unclassical, anxious Hercules, wiry not beefy, a striking antithesis to the familiar Neapolitan giant leaning on his club, worn out by carrying his huge muscles, set against our slender Hercules who contains a nervous soul.

He is paired with St Michael, a Christian knight. They represent spiritual and worldly heroism respectively, we are told. The two are placed symmetrically in most reconstructions, but they make an odd pair. The saint is sleek and elegant. His wings take some working out and look unnervingly like living tissue. Common opinion holds that this figure cannot be Giovanni’s, and the choice usually lands on Tino di Camaino, one of Pisano’s ablest pupils who went on to a successful career in which the smoothness of St Michael is frequently repeated.

The earliest secure attribution to Giovanni Pisano consists of two eagles on the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia (see below) where he worked under his father Nicola. They are extraordinarily lively, engaged in harsh dialogue with each other. A similarly intense interest in the life of beasts keeps turning up throughout Giovanni’s career. In the Pisa pulpit we have the little winged sprites trapped between the Evangelists, the oversized eagles squeezed in between female Virtues and, most alarming of all, the two lions, caryatids, looking up from the prey they are in the middle of tearing to pieces. This ferocity extends the range of emotion captured in the monument to include vivid and convincing rage. Giovanni’s animals usually convey a serious interest in the place of primitive urges in the whole territory of consciousness, not just playing around the edges of the page as in medieval manuscripts.*

Besides the wonderful replica of one of Giovanni Pisano’s crowning works in the cast court, the V & A possesses two precious fragments securely attributed to this sculptor whom Henry Moore ranked with Michelangelo as the greatest of Italian artists. The rarest is an ivory Christ from a crucifix, in which we find both the energetic movement familiar in his work in the writhing hair played against the crown of thorns, and his characteristic focus on the expressive power of the rib cage.

The other fragment is a bust-length piece from the projects Moore regarded as the summit of Giovanni’s achievement. These were the figures, half-figures and sculptural groups which had been exposed to the weather on the Pisa baptistry and the façade of Siena cathedral. The effects of weathering and the modern preference for Giovanni over his father Nicola are strongly connected. Henry Moore almost admits to reading the wear and tear visible on the outdoor pieces as a kind of fortuitous boldness, as if Giovanni’s characteristic expressionist urgings are pushed further by the weather, as if its ferocity could be attributed to the sculptor, or was, without conscious agency or intention, causing the sculptor to become more himself than ever, or calling into existence the sculptor Pisano would have been if he were Moore’s contemporary. Something similar is at work in my fierce resistance to the idea that Giovanni Pisano is a Gothic sculptor. He is so much fresher than that, and there is something sound and true in the magic that weather has worked on the outdoor sculpture, which shows us the direction in which to push or read the indoor work to see the depths that lie there waiting to be coaxed forth by sympathetic, anachronistic eyes.

Michael Ayrton thought the Siena figures the most philosophically ambitious and monumental in scale of all his work, a group of fourteen prophets and sibyls in dialogue and contention with one another, passionate, visionary drama of immense historical and psychological scope. The V & A’s chunk of the Hebrew prophet Haggai from that facade is a powerfully expressive piece in which discoveries made earlier in the project about how to convey intense meaning and precise impressions over distance were developed further, involving bold use of the drill to show agitation of the features, and especially the beard, which revealed the movements of the soul.

Along with these bold textural effects went the famous tensed and craning neck, which Moore was perhaps first to intuit was more than a means of projecting the head beyond the parapet on a façade, but a novel expression of a figure’s intellectual fire as well. Pisano brought this discovery down from the higher reaches of buildings and we find it again in Ecclesia and a couple of her Virtues.

And we even come upon a miniature equivalent of bold and sketchy textures for conveying expression from afar on the smaller scale of the relief, admittedly more tellingly present on the pulpit in Pistoia than in Pisa.

Giovanni Pisano was a complex and fascinating character, revealed most nakedly in two features which were completely omitted when the V & A cast of his Pisa pulpit was made, long inscriptions which remain ambiguous and difficult to interpret to this day. The upper one, which appears just below the reliefs, is generally regarded as boastful. The second, longer and running at floor level, is seen by Pope-Hennessy as a complaint lodged against an envious world. Ayrton reads it very differently, as a despairing confession of failure by an artist who has fallen short of an unattainable goal. Did he end frustrated and defeated by the world, or tragically uncertain of his own genius?

The two inscriptions are printed in full, in Latin and English translation, in Pope-Hennessy’s Italian Gothic Sculpture. The translation of the second inscription in Ayrton’s Giovanni Pisano Sculptor, a rewarding collaboration with Henry Moore and an Italian photographer, does not come out in the same place and isn’t even spoken by the same imagined speaker.

*One of the most surprising items in the Pisani literature is a 9-page analysis of the extra lion footprints on the lion’s pedestal, signs of a struggle, according to the authors. Palozzi, L & Bergkvist, G, 2018, ‘A brief cross-disciplinary study of lion paw prints in Giovanni Pisano’s Pisa Pulpit (1302–10): On the seventh centenary of Giovanni Pisano’s death’, Source (notes on the History of Art), vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 215- 224. https://doi.org/10.1086/699963

Trying for the most ferocious illustration, I inadvertently chose the lioness. My own inspection of these wonderful animals had not extended as far as the ground they stand on. With understandable satisfaction, the authors of this article observe that they seem to be the first in its 700 years of existence to notice these features of the lion’s marble pedestal: two complete footprints, one facing in the lion’s direction of travel, the other backward, and various signs of the scuffle with the prey impressed in the soft soil, apt at recording such marks. They analyse both the accuracy and the purposeful inaccuracy of this lion’s anatomy, and make a fascinating case for the significance of the two paw-prints in the history of art. They see them as Giovanni’s way of releasing his lion from its limited role as a support for a pulpit by suggesting an existence for him outside the frozen posture over his victim. The prints encourage us to imagine him moving as we do freely through the grove. These easily overlooked traces of the activity of the lion, perhaps an afterthought of the sculptor’s, can be seen as one of his boldest subversions of the conventions of liturgical equipment, and a source of guilty enjoyment to those who happen to notice them. Once again, Giovanni Pisano is moving toward freeing the artist and his work from subservience to a patron, the Church.

Neither the makers nor the later keepers of the plaster cast seem to have noticed or taken care to preserve these paw-prints, which have evidently got further scuffed and filled in over time. Recent photographs of the indentations in the marble original in Pisa show another kind of defacement, which has smoothed whatever Pisano carved into a series of blob-shaped hollows, in which it is remarkable that Palozzi and Bergkvist could recognise the lion’s prints.

Fig. 3. Giovanni Pisano, lion hunting his prey, 1302–10 (top view with detail of paw prints below). Carrara marble; print A: 5 ⅛ in. (13 cm); print B: 4 . in. (12 cm). Pisa Cathedral. Photographs: Ivan Bianchini. The detail shows the metacarpal pad (MC) and the pads of digits II–V of paw print A, and the metatarsal pad (MT) and the pads of digits III–V of paw print B.

Translation/ explanation of caption: Metacarpal = front paw, metatarsal = back paw. The two prints almost touch at their back edges. The left-hand, front-paw print faces inward toward the lion’s body, pointing upward toward 10 o’clock; the right-hand, rear paw points downward toward 4 o’clock. The front paw is 5 inches wide; the rear paw 4 inches. Unless the whole thing was a private joke, when new the prints must have been more detailed, and more recognisable.

It is a detail, and a small piece of the puzzle, but one more sign of Giovanni Pisano’s study of his subjects from life, centuries before this became commonplace.

Thus, in at least two ways we can’t experience Hilliard’s work fully when standing directly in front of it. This sounds a drawback and so it seems at first, but I’ve come to feel it as a kind of richness—Hilliard dawns on you in stages, slowly. In one of his earliest surviving works, a circular bust-length image of Leicester, the Queen’s favourite, a painting less than two inches across, the background seems an anonymous grey to the naked eye, but is known to have had special attention lavished on it, to be founded on a base of silver which has been selectively burnished to bring it out in patches, probably with an instrument like a weasel’s tooth mounted on a stick, as described in Hilliard’s treatise The Arte of Limning.

Thus, in at least two ways we can’t experience Hilliard’s work fully when standing directly in front of it. This sounds a drawback and so it seems at first, but I’ve come to feel it as a kind of richness—Hilliard dawns on you in stages, slowly. In one of his earliest surviving works, a circular bust-length image of Leicester, the Queen’s favourite, a painting less than two inches across, the background seems an anonymous grey to the naked eye, but is known to have had special attention lavished on it, to be founded on a base of silver which has been selectively burnished to bring it out in patches, probably with an instrument like a weasel’s tooth mounted on a stick, as described in Hilliard’s treatise The Arte of Limning. Hilliard’s self-portrait inscribed with a date of 1577 takes on a new meaning when placed in his French period when it was painted, where he saw artists accorded higher status, and was welcomed into learned circles around writers like Ronsard, newly identified as one of his sitters. Hilliard’s little self-portrait shows him as another gentleman, not a mere artisan, a claim picturesquely fleshed out in the treatise. The liveliness of expression in the features, especially the eyes, the hair and the set of the mouth, is extended by the flying bits of the clothes, as if rocked by a breeze, and the dematerialised edges of the ruff, which will become an even more outlandish feature of many later Hilliard portraits, where regular pattern and an opposing force are locked in endless struggle.

Hilliard’s self-portrait inscribed with a date of 1577 takes on a new meaning when placed in his French period when it was painted, where he saw artists accorded higher status, and was welcomed into learned circles around writers like Ronsard, newly identified as one of his sitters. Hilliard’s little self-portrait shows him as another gentleman, not a mere artisan, a claim picturesquely fleshed out in the treatise. The liveliness of expression in the features, especially the eyes, the hair and the set of the mouth, is extended by the flying bits of the clothes, as if rocked by a breeze, and the dematerialised edges of the ruff, which will become an even more outlandish feature of many later Hilliard portraits, where regular pattern and an opposing force are locked in endless struggle. Perhaps the most astonishing fruit of Hilliard’s time in France is the recently discovered miniature of the young king Henri III which combines hieratic flatness with subtle traces of red around the eyes, of blue shadow in the temples, with odd life in hair, jewels and lace–lace a little universe in itself, melting away to nothing at the edges and tangling to thickets in its densest parts.

Perhaps the most astonishing fruit of Hilliard’s time in France is the recently discovered miniature of the young king Henri III which combines hieratic flatness with subtle traces of red around the eyes, of blue shadow in the temples, with odd life in hair, jewels and lace–lace a little universe in itself, melting away to nothing at the edges and tangling to thickets in its densest parts.

The miniature above goes about as far as you can go in stretching the image to the frame, engorging the space completely, except where the hair takes over at the top, and on the right where the same ruff that lies flat against the background tilts upward, as if it has brushed against and been deflected by the wooden frame. This asymmetry, actually slight, is subtly disorienting, as if something within the image is moving, as the right-hand half of the picture becomes restive.

The miniature above goes about as far as you can go in stretching the image to the frame, engorging the space completely, except where the hair takes over at the top, and on the right where the same ruff that lies flat against the background tilts upward, as if it has brushed against and been deflected by the wooden frame. This asymmetry, actually slight, is subtly disorienting, as if something within the image is moving, as the right-hand half of the picture becomes restive.

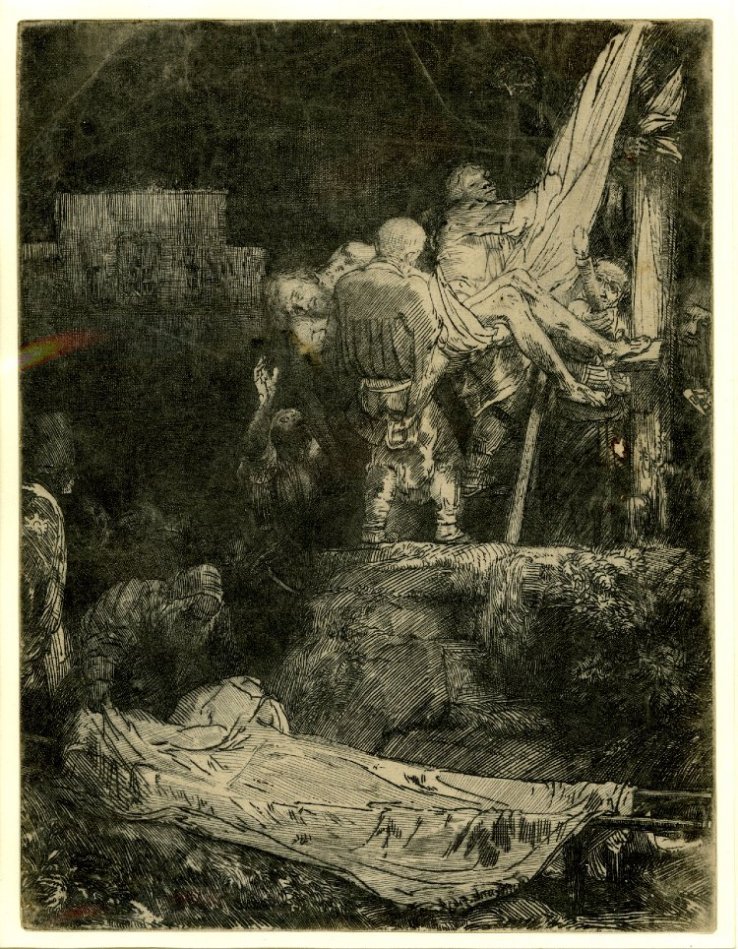

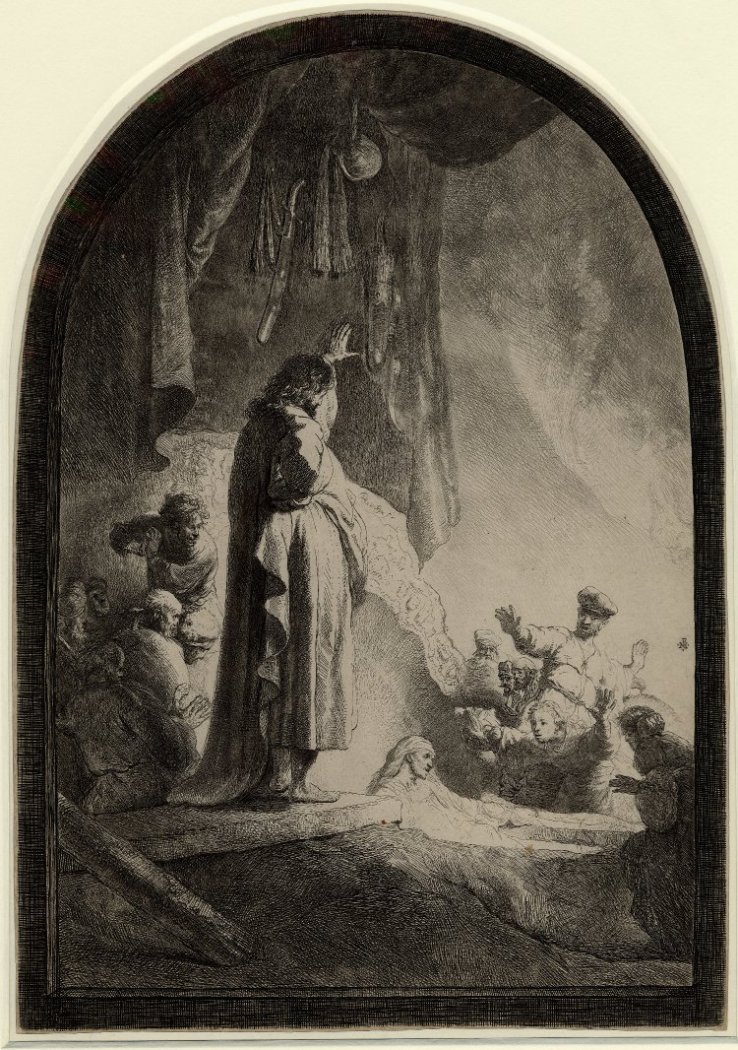

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically.

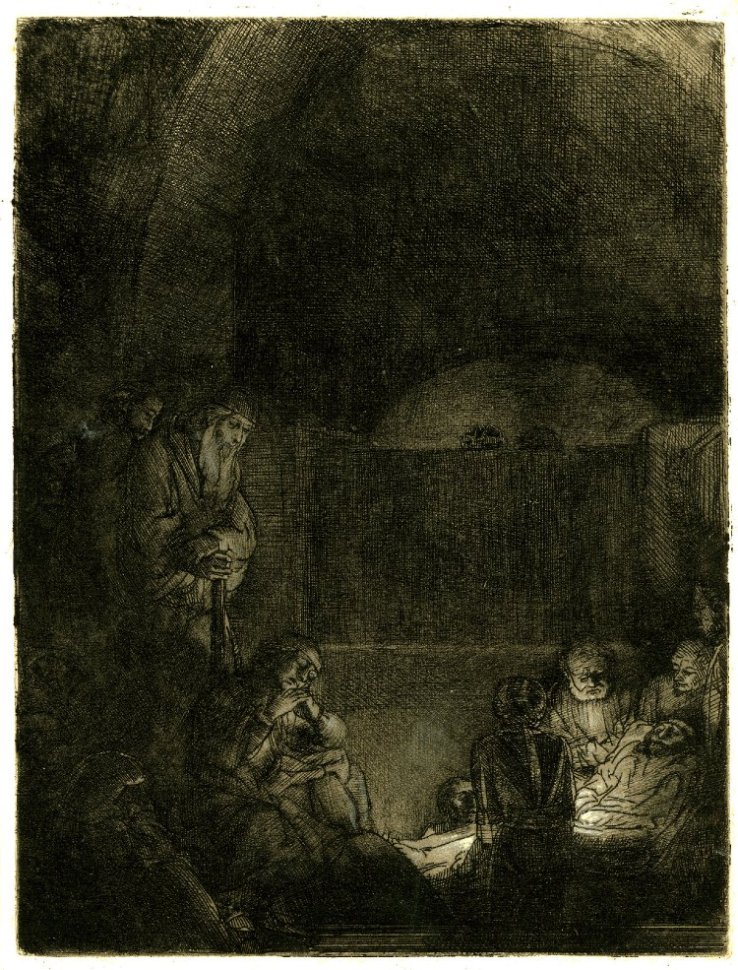

One of the earliest etchings in the little exhibition of his prints and drawings now at the British Museum, a large, showy Raising of Lazarus, made me wonder how he (or anyone else) could ever go beyond it. The lighting effects are so startling, the gestures though exaggerated so confident and so clearly set off from one another. A single action becomes a whole series of them. The later Rembrandt might cringe at the idea of making the main figure three times the size of the others, but we’re not having such thoughts now, caught up in marveling at the richness of light and dark tones jostling each other so energetically. Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

Ten years later he does the raising of Lazarus more quietly but with greater intensity, on a smaller plate with a reduced tonal range. Gestures are less dramatic, if they show up at all. Facial features are almost too small to pick out, but the tilts of the little figures’ heads are powerfully expressive instead, thrust forward, drawn back, lowered, turning aside—all these and more are employed in this small print. Christ isn’t even looking directly at Lazarus but slightly downward, pondering.* Has anyone ever done a human group with such attention to the varied states of everyone in it?

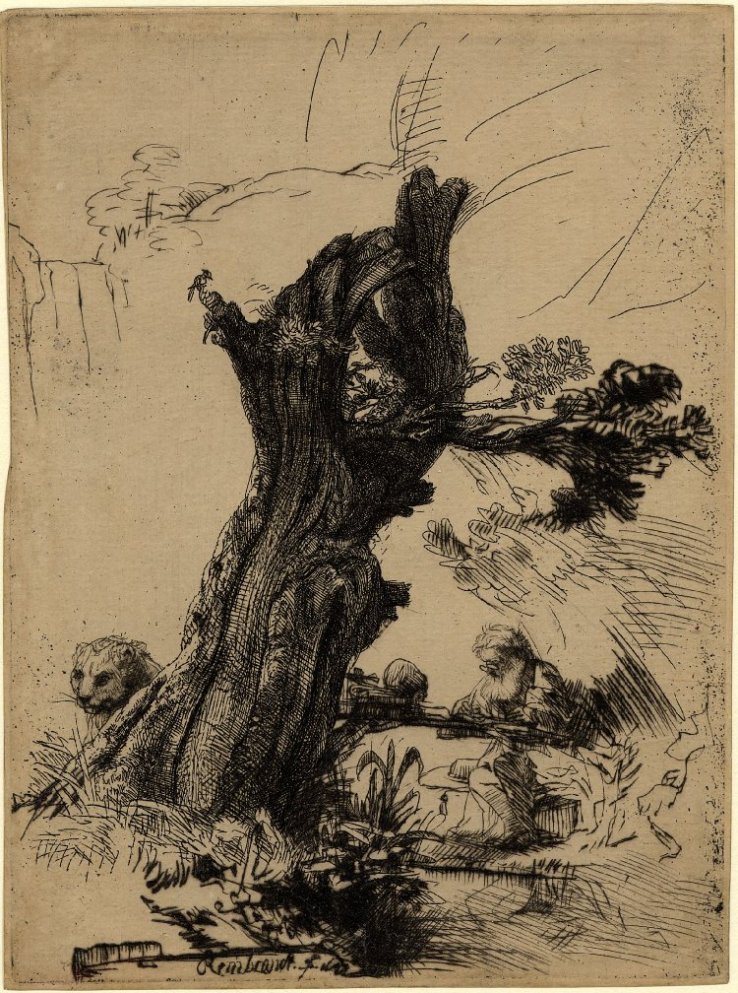

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Another young man holding a whole cohort of old ones entranced with his tales, like Christ among the doctors, but this time Joseph recounting his dreams to the other prisoners, a subject easier to give a comic twist, in part by clothing them all in Egyptian finery. It is an exercise in filling up space, and he does it most ingeniously, including a bedroom setting as in Genesis, a kitchen visible in a slit at the edge and a dog obliviously licking itself. Joseph is the brilliant invention of a novelist, a little businessman who is believable as the soon-to-be administrator of the whole Egyptian harvest.

Then

Then