The Italian Futurists set themselves one of the most impossible goals in sculpture—to capture movement itself, not just a moving body but the idea of movement transcending any actual movement. In painting this sometimes came out in stuttering images like time-lapse photography, so the moving body appeared in multiple images minutely separate from each other, more a conception than a depiction of motion, not Boccioni’s way, whose cyclist or footballer interpenetrated his surroundings via atmospheric planes until the very idea of distinct entities was called in question.

Baroque sculptors like Bernini had approached the problem through the sculptural group—Apollo chasing Daphne, who turns into a laurel tree before our eyes, a half-completed process in the resulting sculpture, which showed a set of intermediate stages all at once, a feat which required detailed inspection to appreciate the full complexity of the ‘movement’.

Or in Bernini’s astonishing later work, the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, a combination of a violent frozen motion (the angel’s), and the liquefaction of a human body expressed as a lengthy tremor in her clothes (the saint’s), a piece of virtuoso carving which represents a spiritual orgasm as a rippling motion that one can hardly believe the sculptor has been able to render in stone, which doesn’t actually move.

This famous ecstasy perhaps comes nearest in earlier centuries to what Boccioni was trying to do in the series of striding figures who culminated in Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, an unwieldy title expressing the high metaphysical ambitions of this exorbitant work.

In its bronze form (actually coppered brass in the two earliest cases), varnished deep brown or polished to a golden sheen, this is Boccioni’s best-known work and probably the most powerful thing any Futurist ever did. As far as most of us knew, Unique Forms of Continuity stood there in lonely eminence, a single outrageous extravagance Boccioni never tried to repeat.

A recent exhibition at the Estorick collection in North London restored the missing context of this well-known work in the most vivid way. It has long been known to students of Boccioni that at his premature death the sculptor left behind a studio full of large plaster sculptures which led up to or grouped themselves around Unique Forms.

Soon after his death his family moved from Milan to Verona and entrusted Boccioni’s unwieldy sculptures to Piero da Verona, apparently a friend, but not an artist who appreciated Boccioni’s work (Marinetti calls him an ‘envious passéist’). He kept them for 12 years, but then consigned them to the local dump where they were immediately broken up.*

After learning of this, Marinetti let out horrified laments, bought the surviving plaster of Unique Forms in 1928 and commissioned the first bronze casts in 1931. Until now, that was that. About ten years ago, so I was told, the digital artists Matt Smith and Anders Raden got the idea of using surviving photos of the vanished works to reconstruct them. The useful pamphlet which accompanied the exhibition leaves out the genesis of the project in detail—who thought of it, how they gathered support and how the work proceeded. There are a few glimpses—apparently, important photos were discovered late in the process, but we don’t know which, or why they were important.

Four sculptures were reconstructed, three large striding figures and a fascinating ‘portrait’, smaller and more self contained, which looks as if it’s based on Boccioni’s drawings and prints with his mother as subject. There are three other important missing sculptures and we can only guess why further reconstructions weren’t undertaken, a lamentably ungrateful response to one of the most imaginative applications of new technology to understanding works of art.

For this ingenious project, in some ways more like a geekish prank than solemn academic research, fills me with wonder, and I want to know more about it than the current publication allows. It’s no accident that none of the sculptures were cast in bronze or any other durable substance in Boccioni’s lifetime, and thus remained easy prey to destruction. In the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture Boccioni expresses strong aversion to both marble and bronze, which belong to the static sculpture of the past. In the Manifesto he lists his preferred materials (glass, wood, cardboard, iron. plaster, horsehair, leather, cloth, mirror, electric lights, etc) and mocks the idea that plastic works should consist of a single material.

I think I can guess why Smith and Raden didn’t tangle with Head + House + Light or Fusion of a Head and a Window, both from 1911, which exhibit more unruly combinations of more diverse materials, like braided human hair to represent human hair and forests of wooden slats for the decomposing window frame.

The wilder assemblage of assorted materials seems a literalism Boccioni was leaving behind, but there are still inescapable paradoxes in reproducing his works in a single material. Old photos show that the jutting elements of Synthesis of Human Dynamism were carried out in painted wood with the nail-heads exposed not concealed.

Synthesis is regarded by Smith and Raden as the earliest of the works they have reconstructed, furthest from Unique Forms, treated throughout as the goal to which the process of creation uniting the four striders always unconsciously strove, a teleology I tried to resist, wanting to find virtues in the ‘earlier’ ones which Unique Forms had to sacrifice in pursuit of its more philosophically pure notion of dynamism. In the end I relented, and admitted that the series made more sense as a single progress than as four paths to different goals.

The results of the experiment, four three-dimensional digital models, are a modern equivalent of the plaster casts of the nineteenth century, which reproduce a work of art with uncanny accuracy in a different, preferably very different, place from its actual location. In the present case they replace not stone, but plaster, with… not plaster but a kind of ghostly, metaphysical plaster, ‘cast’ from the ‘originals’, which are photographs, taken from random angles and distances by a ragbag of photographers, whose own idiosyncrasies we (or the digital artists) must work out and try to take account of.

After dedicated efforts to get sizes and proportions right, all the data are converted by 3D printing into a kind of neoclassical perfection, or what Boccioni’s sculptures would have looked like if they were fabricated in the marble he despised. It turns out that the hardest things to reproduce in milled foam or neutral, anonymous laminate are the imperfections of the plaster, the scuffs and smudges left by the life of the studio, the gouges and tiny craters left by the sculptor’s tool or the space created by the falling-out of a minute pebble.

Apparently Boccioni wasn’t above adding or deepening shadows on the plaster with grey paint. Once or twice in the old photos we catch him at it. In the Manifesto he explains how to make edges fade to infinity or forms pass through each other by such means, not major principles of his practice like centrifugal organisation, spiral rather than pyramidal form, or the abolition of the special value of the profile. Still, the grey paint played its part in the great Bergsonian drama and was sometimes the safest way to make sure a certain element appeared to move in two directions at once.

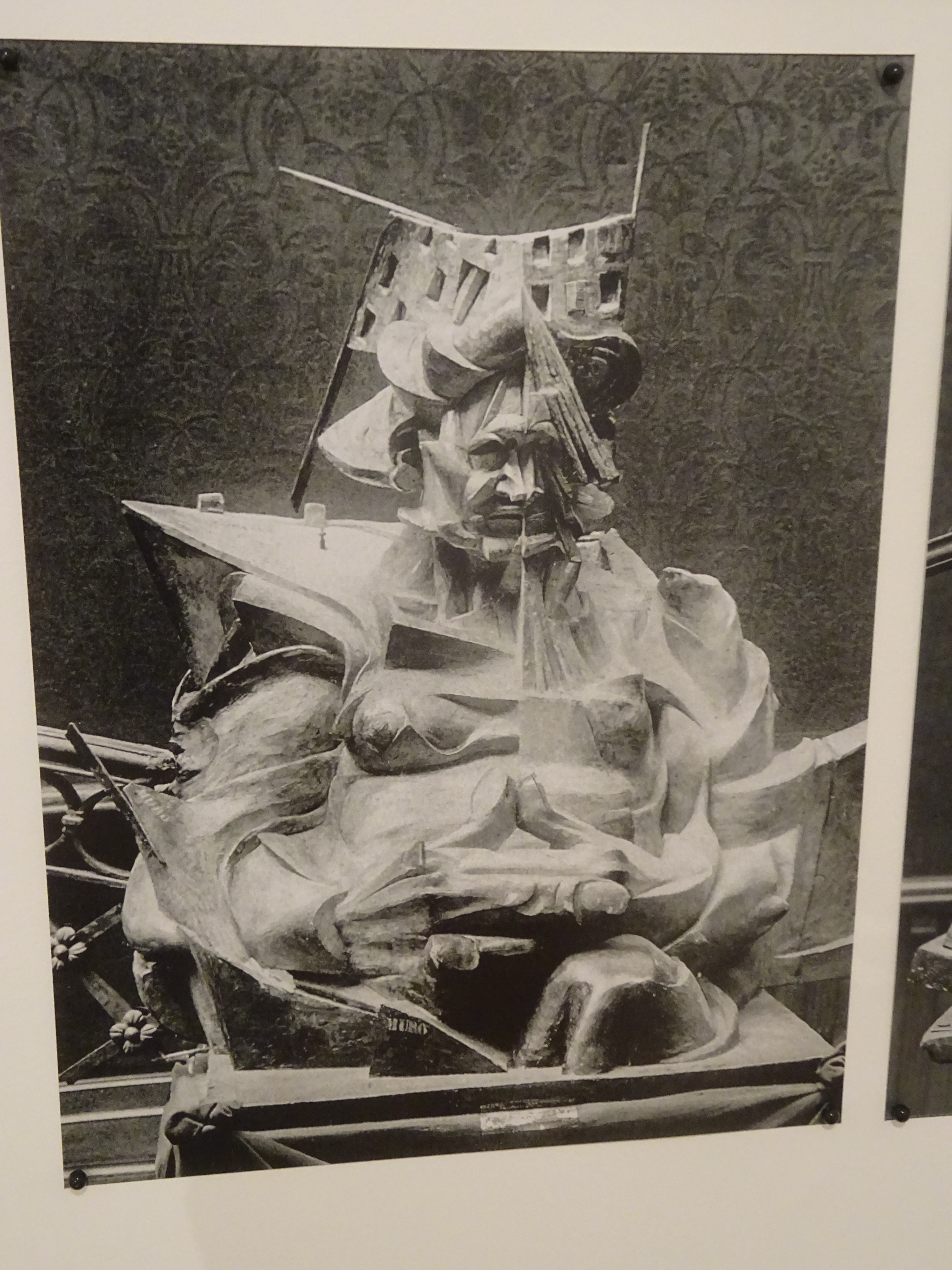

The largest, earliest and gawkiest of the striding figures, Synthesis of Human Dynamism stands out among the four for lack of smooth synthesis, one of Boccioni’s watchwords, as opposed to the heartless analysis of traditional sculpture. He is scathing about the conventional nude as a subject, the body stripped bare, which he intends to replace with atmospheric planes that connect and intersect, rendering the mysterious sympathies and affinities that create reciprocal influences between bodies. In this early stage there is a bulky muscular figure trapped in a geometric armature from which the bodily elements struggle to emerge. You keep recognising various components but don’t understand the logic that fuses them together or splits them apart. The number of parts is overwhelming, and whatever Boccioni says, it feels just as disunified as analytical cubism at its most fractured.

From certain angles the ‘feet’ of the giant look covered in feathers, and the work’s whole effect seems one of the most disunified ever, diverse as only forms produced by a centrifuge could ever be in the real world.

From certain angles the ‘feet’ of the giant look covered in feathers, and the work’s whole effect seems one of the most disunified ever, diverse as only forms produced by a centrifuge could ever be in the real world.

The next figure, Speeding Muscles, seems less tormented or riven by conflict. The forms themselves and transitions between them are smoother and the motion is more like melting than breaking to pieces.

Again there are surreal penetrations of one disparate form by another, in this case a skull and a multi-storey building, which can’t help looking comical in its slow collapse. Two of the striders are a stark plaster-white, while this one is the colour of pale brown sugar. We assume it has been coloured, while the other two have been left the natural colour of the material, milled foam or 3D printing. It seems that the contrary is the case – the white is an added paint layer, and the pale sugar colour is ‘natural’. The more granular texture of this one, which makes it look as if it were actually made of sugar, introduces the alien naturalism of a material never seen before.

The idea of 3D printing will become more familiar, and then the laminate structure so easily visible in Synthesis–which makes me think it is the ultimate hypothetical object, more glue than primary substance, a truly metaphysical ‘thing’, ‘printed’ like a statement, whose nearest analogue in the real world is a living tissue made of words–then that self-division into a series of selves will seem the most normal thing in the world.

The third strider, Spiral Expansion of Muscles in Movement, has trumped the more accessible lower-level transpositions and lost various resemblances to ordinary objects. Yet Boccioni can’t escape entirely into his description of all his works as bridges between two infinities, inner and outer. From the most comprehensive vantage Spiral Expansion still looks a lot like a muscular human body taking off its clothes, a more complex and articulated stage of existence than a nude just lying around, but another conglomerate that hasn’t really found a use for its complexity.

One of Anders Raden’s other projects gives back the Venus de Milo’s missing arms, while Boccioni removes the arms entirely from his figures, as largely extraneous to pure concepts of human dynamism. The number of copies of Unique Forms has crept up since the 1960s and is now hard to calculate, but Boccioni never pursued the idea of multiples, as Matt Smith has done for some time on his website, offering various sizes of one of the striding figures he has reconstructed. The display at the Estorick included a set of small models of all four striders, reproduced to a consistent scale and laid out in a diagonal line to make comparisons easier. I wondered afterward how Boccioni would feel on seeing his difficult journey reduced to toy size.

*This appears to be only the latest version of the sculptures’ fate. They’ve also been destroyed by a violent storm after the open-air exhibition of 1916, or turned over to the sculptor Virgilio Brocchi, whom Boccioni had portrayed in an important transitional work, who negligently let workmen clear them (Boccioni’s sister’s account). Further inconsistencies, like the various dates assigned to the destruction, remain to be sorted out by further research.

Fourth reconstruction: Empty and full Abstracts of a Head, 1912/ 2019