Like Sir John Soane’s Museum, Strawberry Hill is one of those places it seems a near-miracle to find arriving intact in the present. Except, of course, that Strawberry Hill isn’t really intact, most of the time, meaning that unlike the Soane it’s been stripped of its contents, encrustations that seem almost part of its flesh.

For a few months recently many of them re-appeared there, and the difference was profound. So, for a short while, you could get a real living sense of Walpole as a collector, and of how his collection turned his house into a physical analogue of his imagination.

Like Soane’s, Walpole’s house and collection first appear to us fully formed and grown to their maximum extent. We haven’t seen them develop organically, putting down layer after pearly layer, not according to longstanding plan but in a series of inspirations or profound gulps of imaginative air. There’s nothing very logical about how the process proceeds; it’s more like an accumulation of associations than simple numerical increase.

One of the most revealing indications of the way things went forward is the story of the Holbein Room, which got its start from Walpole’s buying Vertue’s tracings of 33 of Holbein’s portrait drawings of Henry VIII’s courtiers, so the most famous room in the house arose from the purchase of certain special pieces of paper. And they weren’t even originals, but copies–wonderful copies, but still copies. On top of this, experts will tell you that they’ve browned horribly over time and their lines have all been crudely strengthened with graphite on top of the original red chalk.

This is no ordinary house, whose maker was inspired to create one of its most memorable spaces because he had just acquired the right things to put in it. Decoration came before structure, as Semper was later to theorise. The house took over the life, and then a rowdy crowd of strong objects took over the house. Walpole virtually admits that the house was haunted by its contents, and perhaps it was the case that the later spaces grew more exaggerated to keep up with the emotive charge of the collection.

Walpole is sometimes described as the last of the eighteenth century eccentrics, jumbling together discordant objects to create a big cabinet of curiosities, not confined to one or two rooms but spreading uncontrollably over more and more space, so Walpole’s building project only exists to keep up with his obsessive accumulation. Various remarks support this view, and his name for his most precious possessions is ‘Principal Curiosities’.

Yet there are strong currents that lead away from the idea of the collection as diverting jumble. Above all, there’s The Castle of Otranto, the first of a dangerous new genre of fiction, generally regarded as a proto-Romantic bursting-forth of long-suppressed unconscious forces, for which Gothic provides a convenient historical cover. Walpole claimed the novel was provoked by a dream in which a monstrous mailed fist appeared at the top of a Gothic stair like the one he’d just been building, which passed on its climb an Armoury stocked with suits of empty armour, and a selection of weapons taken in the holy wars (in Palestine) by an ancestor recently discovered through his researches. Anyone the least bit suggestible passing these fragments of warriors today, topped off with the very same plumes of black feathers whose shuddering in gusts of air unmans Manfred in the Castle, probably trembles inwardly.

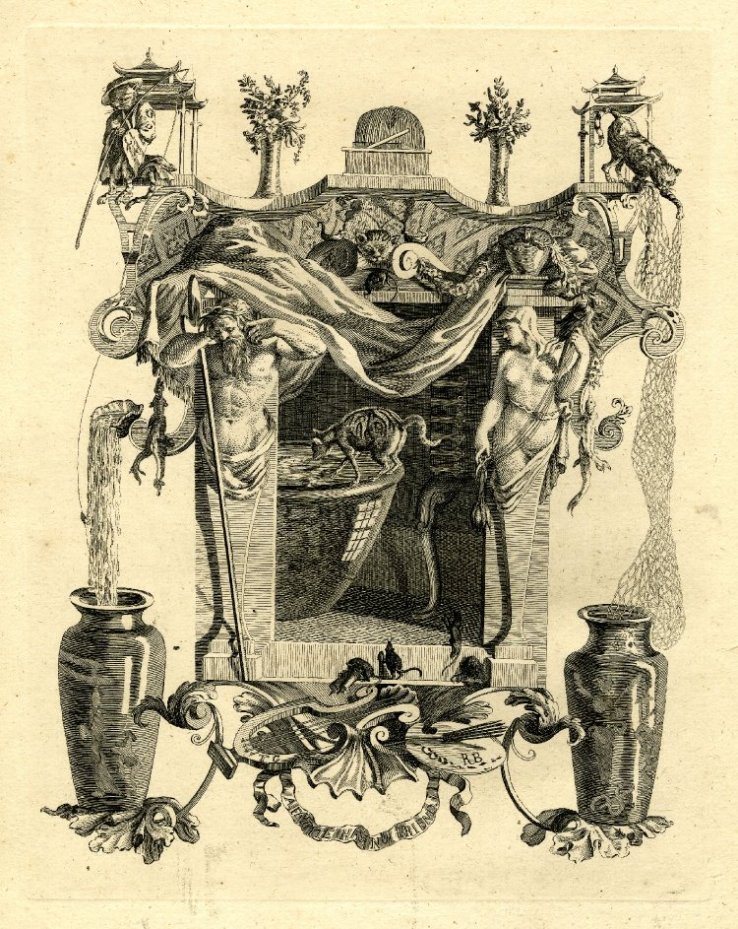

Walpole didn’t actually build the incidents in The Castle of Otranto into the spaces of Strawberry Hill. He didn’t need to. He had seen an ancestor step down from an old portrait in a dream and he filled the place with portraits. Architectural collapse kills one person and frees another from prison in the novel; in the villa no actual deaths, unless we count his favourite cat who fell into a goldfish tub of Chinese porcelain that greeted visitors before they reached the house. The cat’s death (which actually happened in London) inspired a poem of Gray’s and a couple of very extreme illustrations by Bentley, who designed many details at Strawberry Hill. The frontispiece shows the cat perched on the rim looking in, surrounded by a riot of Baroque detail, swags of cloth about to fall, Chinese fountains gushing, Chinese sages leaving their perches, mice dipping in and out of borders, mouldings out of true and getting more so, in a word an active moment of collapse that promises worse to come. The other illustration is less violent and more sinister. It lets us look down into the tub in which the drowning cat is swirling, and somehow the squashed perspective makes us feel we won’t be able to keep from falling in too, an absurd but powerful sensation.

Horace Walpole was unusually conscious of his mortality. Collecting seems to have been for him a way of confronting it actively, not running from it. At some point in the catalogue of the big V & A exhibition of 2009-10, of which the present exhibition is occasionally an expansion, but more often, a reduction, a writer says Walpole was lucky because the great collectors he met in Rome were all older than he was, and so he could gobble up choice bits when their collections were sold. This is far from how he would have seen it. Someone conscious of long historical vistas does not imagine that they will end with him.

Unlike Soane, Walpole made no provision for his collection to survive him in any straightforward sense. There is something wonderful and also crazy about the current effort to put as much of Walpole’s collection as possible back in its original locations in his house. Of course this would have much less chance of coming to pass if he had not recorded it in such obsessive detail. What is that but the most urgent wish arising from the most paralysing fear, that the whole arrangement not be lost but maintained forever in exactly the layout we find it in now? A Description of the Villa of Mr Horace Walpole, what a misleading description of what lies in front of us—‘An Exhaustive Description?’ Not nearly strong enough, ‘A Recreation in paper form of the vanished house and collection of’ would bring us nearer. He talks of his house as his nutshell (like a crab, a nut lives in its shell), or as a house of paper, and thinks of packing up his new Gothic stair and sending it to Horace Mann like a letter. His Description was a form of the house that could be posted like a letter, and would be after his death, like seedlings from a nursery, sent to eighty chosen recipients.

It is very wonderful to have seen even once the rooms at Strawberry Hill full or half-full instead of empty. It is wonderful that the organisers persisted in repeating something so costly in time and effort that some of them had already done once before. Still, what is the point of reconstituting something as accidental as a collection, that is to say, of the treasures that a certain person living in a certain place at a certain time happened to own, temporarily, because he thought he wanted to? You have to be very sure that the collector himself is extraordinary in order to think such a project worthwhile. How do you convince yourself in the case of Walpole?

Those who know them seem to agree that the 48 volumes of Walpole’s letters are the liveliest, most mercurial, wittiest, most informative, and most learned in a special way of their own, human documents to survive from their own century or perhaps any other, and these enthusiasts see the house and collection as crucial physical embodiments of this remarkable individual, so no trouble is too great to bring this restoration closer to completeness.

There’s always been some question about Walpole’s seriousness: how reliable was his devotion to Gothic, how much was it just a diverting form of play? He insists on historical accuracy but look what he does with it—the arched book-cases in the Library are taken from a doorway in Old St Paul’s, a building none of his friends could possibly have seen, the chimneypiece, another arched form, is an amalgam of two royal tombs; five years later, in the Holbein bedroom, an even more promiscuous mixture in closer proximity to each other, a screen from Rouen cathedral, scaled down presumably, a ceiling from a larger space at Windsor, and the fireplace from the tomb of Henry VIII’s last Catholic archbishop. How completely could you ever detach the patterns from their sources? The Catholic connection, for one, was apparently treasured.

A little later still Walpole is wanting the Tribune to have the feeling of a Catholic chapel ‘in everything but being consecrated’, the Tribune modeled after a classical idea of the central kernel of a connoisseur’s collection in a circular space, which in this instance has a Gothic vault lined with tracery of rococo delicacy. So it seems the spaces got denser and in some way more licentious as he went on, crowding his architectural effects and multiplying the encrustation of surfaces. He calls Strawberry his diminutive castle, sometimes just a playful modesty, but he relishes small forms like portrait miniatures, which from the 17c onward are often based on full size paintings.

Walpole might even have enjoyed the fact that the Holbein Chamber is normally decorated with recent copies of Vertue’s (original, earlier) copies, in the strange chequered display he apparently contrived, that fills the walls full, in a quirky zig-zag way. I think that for the exhibition the actual Vertues were there again, but am not sure. In the Tribune was an even more confusing exhibit, the little portrait of the risqué poet Bembo’s mistress Costanza Fregosa, a Raphael (from a private collection) or a not-much-later copy (from a museum in Brescia). Which of the two were we looking at, and which had Walpole owned, a work he thought was by Leonardo because of the landscape background, painted by a different artist?

Walpole could cope with such uncertainties. He tended to believe attributions or to improve on the ones he was given to start with, notorious even in his own time for thinking that his treasures had been owned or worn by kings and princes. His collection is endlessly fascinating, not for its aesthetic excellence, though there are exceptions like the enamelled hunting horn or the Roman eagle, but for the stories Walpole told himself about the pieces, connecting himself in that way to people and events he already knew from various distances in the past. One of the most revealing is a letter from Madame de Sévigné, another famous letter-writer, addressed to him by his friend Madame du Deffand who was impersonating the 17c French writer, of whom Walpole collected relics.

Many of Walpole’s objects shared this condition of relic because Walpole brought himself to believe, for instance, that a Flemish painting of the marriage of a saint showed the marriage of an English king. I don’t think that the fact that Walpole wished the personages in his paintings and objects into people of high rank is evidence of simple snobbery (if snobbery is ever simple), or isn’t only that, but the creation of a kind of poetry of relatedness or mystic union between Walpole and his collection.

Late in his career, he bought an illuminated Psalter, a medieval form painted by a Mannerist artist long after the form had expired in its original sense, which he imagined had been painted by the very best of such throwbacks, Giulio Clovio, a friend of Bruegel’s. He had a special box made to hold it, emblazoned with Walpole heraldry, real and imagined, and finished off with an illusionary grisaille on the lid, which showed a little angel introducing Painting, who held the manuscript ‘illustrated by Don Julio Clovio’ which lay inside the box, to Religion, to whom she wanted to give the book.

This painting by William Lock Junior is a tremendous success, which has fooled many who have seen it, as it had the guard with whom I discussed it. It is hard to see the picture in it at all because it looks like rumpled satin, or a picture of rumpled satin, which you might expect to find on the lid or the lining of such a box. The picture hides itself in the colourlessness of grisaille and the Baroque slipperiness of its forms. It is an archetypal Walpole commission which is passed over undescribed and unillustrated in all the publications I have seen of this object, publications which attend to every other part of this conglomerate except the most interesting and Walpole-like of all, this wispy deceitful joke which pretends a pious Catholic purpose.

In the same room (not where the manuscript was announced or supposed to be) was another object with one of Walpole’s riddling improvements, a gorgeous 16c clock of elaborate early Renaissance design, sitting on an 18c Gothic stand, through whose tracery it dangled its two heavy but at the same time beautifully inscribed (in a 16c hand) weights*, one century threaded through another, or from certain angles entangled in it. I am sure, or at least want to believe, that Walpole thought up this hybrid and had Bentley design it, or that Bentley did and Walpole agreed. The rightness of the match to his other ideas confirms the attribution. Incidentally, the clock is always illustrated without its stand. In other words, stripped of the means by which Walpole made the piece his own.

He was conscious of what he was doing with his historical sources. He joked in a letter that the bishop whose tomb contributed the pattern for the gate to Strawberry Hill, would rather, he was sure, be passed through, than passed over, i.e. ignored by the future. Recently someone has claimed that the house and the collection have a secret centre that would unlock the whole if we knew how to read it. This is the Glass Closet, a locked case like a small room, in the Great North Bed Chamber, the last big addition to the house of the 1770s. The Closet is filled with a strange collection of things, some precious in an obvious way like Queen Bertha’s comb (a Romanesque ivory with a forged inscription, now found to be German not English), others like his exercise books from school, too personal to interest all but a few. I like the idea of a single final secret, but Strawberry Hill is a place of multiple centres, of which there is a wonderful historical series leading from the Stair (1752-3) to the Library (in some ways best of all, 1754) to the Holbein Chamber (1759) and finally the Tribune (1761), all self-sufficient worlds and endless when you are in them, but, sadly, (once again) bare and deprived without their contents (after 24 Feb).

Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill, masterpieces from Horace Walpole’s collection 20 October 2018 to 24 February 2019

*The clock was believed by Walpole to be a gift from Henry VIII to Ann Boleyn. He detected a questionable joke of the King’s in the shape of one of the weights.

Apologies for the images: photographs were not permitted in the house during the exhibition, so the fuller version of Strawberry remains just that much more ephemeral.

That was interesting, I too saw the V and A exhibition and tried to imagine the objects in place at Strawberry Hill. The Beckwith collection was very similar but alas no Fonthill remains. They have done a great job of restoration at Strawberry Hill and I always find it a sign of Walpole’s originality/eccentricity that it was being built at he same time as the classical Marble Hill House so very close by.

Thank you Bob.

LikeLike